Pediatrics

Pediatrics

| Focus | |

|---|---|

| Subdivisions | Pediatric cardiology, neonatology, critical care, pediatric oncology, others (see below) |

| Significant | Congenital diseases,Infectious diseases,Childhood cancer |

| Significant | World Health OrganizationChild Growth Standards[38] |

| Specialist | Pediatrician |

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

| Occupation | |

| Names | |

| Specialty | |

| Medicine | |

| Description | |

| Hospitals,Clinics | |

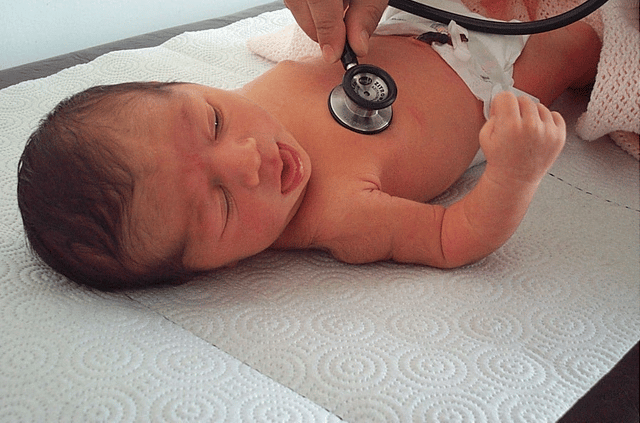

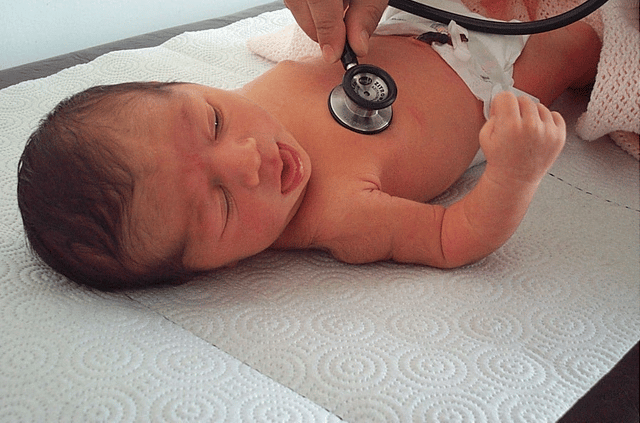

Pediatrics (also spelled paediatrics or pædiatrics) is the branch of medicine that involves the medical care of infants, children, and adolescents. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends people be under pediatric care up to the age of 21,[1] thought usually only minors under 18 are required to be under pediatric care. A medical doctor who specializes in this area is known as a pediatrician, or paediatrician. The word pediatrics and its cognates mean "healer of children"; they derive from two Greek words: παῖς (pais "child") and ἰατρός (iatros "doctor, healer"). Pediatricians work both in hospitals, particularly those working in its subspecialties such as neonatology, and as outpatient primary care physicians.

| Focus | |

|---|---|

| Subdivisions | Pediatric cardiology, neonatology, critical care, pediatric oncology, others (see below) |

| Significant | Congenital diseases,Infectious diseases,Childhood cancer |

| Significant | World Health OrganizationChild Growth Standards[38] |

| Specialist | Pediatrician |

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

| Occupation | |

| Names | |

| Specialty | |

| Medicine | |

| Description | |

| Hospitals,Clinics | |

History

Part of Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, United Kingdom, which was the first pediatric hospital in the English-speaking world.

Some of the oldest traces of pediatrics can be discovered in Ancient India where children's doctors were called kumara bhrtya.[2] Sushruta Samhita an ayurvedic text, composed during the sixth century BC contains the text about pediatrics.[4]*Children's%20Surgery%3A%20A%20Worl]]*nother ayurvedic text from this period is[5]

A second century AD manuscript by the Greek physician and gynecologist Soranus of Ephesus dealt with neonatal pediatrics.[7] Byzantine physicians Oribasius, Aëtius of Amida, Alexander Trallianus, and Paulus Aegineta contributed to the field.[2] The Byzantines also built brephotrophia (crêches).[2] Islamic writers served as a bridge for Greco-Roman and Byzantine medicine and added ideas of their own, especially Haly Abbas, Serapion, Avicenna, and Averroes. The Persian philosopher and physician al-Razi (865–925) published a monograph on pediatrics titled Diseases in Children as well as the first definite description of smallpox as a clinical entity.[8]A%20Medical%20History%20of%20Persia]] [9] Also among the first books about pediatrics waset remediis infantium Ein Regiment der Jungerkinder Versehung des Leibswritten in 1429 (published 1491), together form thePediatric Incunabula, four great medical treatises on children's physiology and pathology.[2]

The Swedish physician Nils Rosén von Rosenstein (1706–1773) is considered to be the founder of modern pediatrics as a medical specialty,[11][12] while his work The diseases of children, and their remedies (1764) is considered to be "the first modern textbook on the subject".[13] Pediatrics as a specialized field of medicine continued to develop in the mid-19th century; German physician Abraham Jacobi (1830–1919) is known as the father of American pediatrics because of his many contributions to the field.[14][15] He received his medical training in Germany and later practiced in New York City.

The first generally accepted pediatric hospital is the Hôpital des Enfants Malades (French: Hospital for Sick Children), which opened in Paris in June 1802 on the site of a previous orphanage.[16] From its beginning, this famous hospital accepted patients up to the age of fifteen years,[17] and it continues to this day as the pediatric division of the Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital, created in 1920 by merging with the physically contiguous Necker Hospital, founded in 1778.

In other European countries, the Charité (a hospital founded in 1710) in Berlin established a separate Pediatric Pavilion in 1830, followed by similar institutions at Saint Petersburg in 1834, and at Vienna and Breslau (now Wrocław), both in 1837. In 1852 Britain's first pediatric hospital, the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street was founded by Charles West.[16] The first Children's hospital in Scotland opened in 1860 in Edinburgh.[18] In the US, the first similar institutions were the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, which opened in 1855, and then Boston Children's Hospital (1869).[19] Subspecialties in pediatrics were created at the Harriet Lane Home at Johns Hopkins by Edwards A. Park.[20]

Differences between adult and pediatric medicine

The body size differences are paralleled by maturation changes.

The smaller body of an infant or neonate is substantially different physiologically from that of an adult. Congenital defects, genetic variance, and developmental issues are of greater concern to pediatricians than they often are to adult physicians. A common adage is that children are not simply "little adults".[21] The clinician must take into account the immature physiology of the infant or child when considering symptoms, prescribing medications, and diagnosing illnesses.

Pediatric physiology directly impacts the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs that enter the body. The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of medications differ between developing children and grown adults.[21][22][23] Despite completed studies and reviews, continual research is needed to better understand how these factors should affect the decisions of healthcare providers when prescribing and administering medications to the pediatric population.[21]

Absorption

Many drug absorption differences between pediatric and adult populations revolve around the stomach.

Neonates and young infants have increased stomach pH due to decreased acid secretion, thereby creating a more basic environment for drugs that are taken by mouth.[22][21][23] Acid is essential to degrading certain oral drugs before systemic absorption. Therefore, the absorption of these drugs in children is greater than in adults due to decreased breakdown and increased preservation in a less acidic gastric space.[22]

Drug absorption also depends on specific enzymes that come in contact with the oral drug as it travels through the body. Supply of these enzymes increase as children continue to develop their gastrointestinal tract.[22][23] Pediatric patients have underdeveloped proteins, which leads to decreased metabolism and increased serum concentrations of specific drugs. However, prodrugs experience the opposite effect because enzymes are necessary in allowing their active form to enter systemic circulation.[22]

Distribution

Percentage of total body water and extracellular fluid volume both decrease as children grow and develop with time. Pediatric patients thus have a larger volume of distribution than adults, which directly affects the dosing of hydrophilic drugs such as beta-lactam antibiotics like ampicillin.[22] Thus, these drugs are administered at greater weight-based doses or with adjusted dosing intervals in children to account for this key difference in body composition.[22][21]

Infants and neonates also have less plasma proteins.

Thus, highly protein-bound drugs have less opportunities for protein binding and leads to increased distribution.[21]

Metabolism

Drug metabolism primarily occurs via enzymes in the liver and can vary according to which specific enzymes are affected in a specific stage of development.[22] Phase I and Phase II enzymes have different rates of maturation and development, depending on their specific mechanism of action (ie. oxidation, hydrolysis, acetylation, methylation, etc.). Enzyme capacity, clearance, and half-life are all factors that contribute to metabolism differences between children and adults.[22][23] Drug metabolism can even differ within the pediatric population, separating neonates and infants from young children.[21]

Elimination

Drug elimination is primarily facilitated via the liver and kidneys.[22] In infants and young children, the larger relative size of their kidneys leads to increased renal clearance of medications that are eliminated through urine. [23] In preterm neonates and infants, their kidneys are slower to mature and thus are unable to clear as much drug as fully developed kidneys. This can cause unwanted drug build-up, which is why it is important to consider lower doses and greater dosing intervals for this population.[21][22] Diseases that negatively affect kidney function can also have the same effect and thus warrant similar considerations.[22]

Pediatric autonomy in healthcare

A major difference between the practice of pediatric and adult medicine is that children, in most jurisdictions and with certain exceptions, cannot make decisions for themselves. The issues of guardianship, privacy, legal responsibility and informed consent must always be considered in every pediatric procedure. Pediatricians often have to treat the parents and sometimes, the family, rather than just the child. Adolescents are in their own legal class, having rights to their own health care decisions in certain circumstances. The concept of legal consent combined with the non-legal consent (assent) of the child when considering treatment options, especially in the face of conditions with poor prognosis or complicated and painful procedures/surgeries, means the pediatrician must take into account the desires of many people, in addition to those of the patient.

Education requirements

Aspiring medical students will need 4 years of undergraduate courses at a college or university, which will get them a BS, BA or other bachelor's degree.

After completing college future pediatricians will need to attend 4 years of medical school (MD/MBBS) and later do 3 more years of residency training, the first year of which is called "internship."

After completing the 3 years of residency, physicians are eligible to become certified in pediatrics by passing a rigorous test that deals with medical conditions related to young children.

In high school future pediatricians are required to take basic science classes such as, biology, chemistry, physics, algebra, geometry, and calculus and also foreign language class, preferably Spanish (in the United States), and get involved in high school organizations and extracurricular activities.

After high school, college students simply need to fulfill the basic science course requirements that most medical schools recommend and will need to prepare to take the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test) in their junior or early senior year in college.

Once attending medical school, student courses will focus on basic medical sciences like human anatomy, physiology, chemistry, etc., for the first three years, the second year of which is when medical students start to get hands-on experience with actual patients.[24]

Training of pediatricians

The training of pediatricians varies considerably across the world.

Depending on jurisdiction and university, a medical degree course may be either undergraduate-entry or graduate-entry.

The former commonly takes five or six years, and has been usual in the Commonwealth. Entrants to graduate-entry courses (as in the US), usually lasting four or five years, have previously completed a three- or four-year university degree, commonly but by no means always in sciences. Medical graduates hold a degree specific to the country and university in and from which they graduated. This degree qualifies that medical practitioner to become licensed or registered under the laws of that particular country, and sometimes of several countries, subject to requirements for "internship" or "conditional registration".

Pediatricians must undertake further training in their chosen field.

This may take from four to eleven or more years, (depending on jurisdiction and the degree of specialization).

In the United States, a medical school graduate wishing to specialize in pediatrics must undergo a three-year residency composed of outpatient, inpatient, and critical care rotations.

Specialties within pediatrics require further training in the form of 3-year fellowships.

Specialties include critical care, gastroenterology, neurology, infectious disease, hematology/oncology, rheumatology, pulmonology, child abuse, emergency medicine, endocrinology, neonatology, and others.[25]

In most jurisdictions, entry-level degrees are common to all branches of the medical profession, but in some jurisdictions, specialization in pediatrics may begin before completion of this degree.

In some jurisdictions, pediatric training is begun immediately following completion of entry-level training.

In other jurisdictions, junior medical doctors must undertake generalist (unstreamed) training for a number of years before commencing pediatric (or any other) specialization. Specialist training is often largely under the control of pediatric organizations (see below) rather than universities, and depend on jurisdiction.

Subspecialties

Subspecialties of pediatrics include:

(not an exhaustive list)

Adolescent medicine

Clinical informatics

Developmental-behavioral pediatrics

Genetics

Headache medicine

Hospice and palliative care

Medical toxicology

Neonatology

Pediatric allergy and immunology

Pediatric cardiology Pediatric cardiac critical care

Pediatric critical care Neurocritical care Pediatric cardiac critical care

Pediatric emergency medicine

Pediatric endocrinology

Pediatric gastroenterology Transplant hepatology

Pediatric hematology

Pediatric infectious disease

Pediatric nephrology

Pediatric oncology Pediatric neuro-oncology

Pediatric pulmonology Sleep medicine

Pediatric rheumatology

Sleep medicine

Social pediatrics

Sports medicine

Other specialties that care for children

(not an exhaustive list)

Child neurology Brain injury medicine Clinical neurophysiology Endovascular neuroradiology Epilepsy Headache medicine Neurocritical care Neuroimmunology Neuromuscular medicine Pain medicine Pediatric neuro-oncology Sleep medicine Vascular neurology

Child psychiatry, subspecialty of psychiatry

Neurodevelopmental disabilities

Pediatric anesthesiology, subspecialty of anesthesiology

Pediatric dentistry, subspecialty of dentistry

Pediatric dermatology, subspecialty of dermatology

Pediatric gynecology

Pediatric neurosurgery, subspecialty of neurosurgery

Pediatric ophthalmology, subspecialty of ophthalmology

Pediatric orthopedic surgery, subspecialty of orthopedic surgery

Pediatric otolaryngology, subspecialty of otolaryngology

Pediatric radiology, subspecialty of radiology

Pediatric rehabilitation medicine, subspecialty of physical medicine and rehabilitation

Pediatric surgery, subspecialty of general surgery

Pediatric urology, subspecialty of urology

See also

Children's hospital

Pain in babies

American Academy of Pediatrics

American Osteopathic Board of Pediatrics

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

Center on Media and Child Health (CMCH)

Pediatric Oncall

Medical specialty