Eritrean–Ethiopian War

Eritrean–Ethiopian War

| Eritrean–Ethiopian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

supported by: | supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 19,000 killed[17][18] Eritreans died (Eritrea claims) 67,000 died [19] Eritreans died (Eritrea claims ) 20,000–50,000[20] or 150,000[21] killed (other estimates) 5 MiG-29s 1 Aermacchi MB-339[22] | 34,000[23]–60,000[24] Ethiopians killed (Ethiopian claim) 123,000 Ethiopians died [25][26] (Ethiopian clandestine opposition claim) 150,000 Ethiopians died [21] (other estimates) 3 MiG-21s 1 MiG-23 1 Su-25 2+ Mi-35s[27] | ||||||||

The Eritrean–Ethiopian War, one of the conflicts in the Horn of Africa, took place between Ethiopia and Eritrea from May 1998 to June 2000, with the final peace only agreed to in 2018, twenty years after the initial confrontation.[9] Eritrea and Ethiopia, two of the world's poorest countries, spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the war[31][32][33] and suffered tens of thousands of casualties as a direct consequence of the conflict.[34] Only minor border changes resulted.

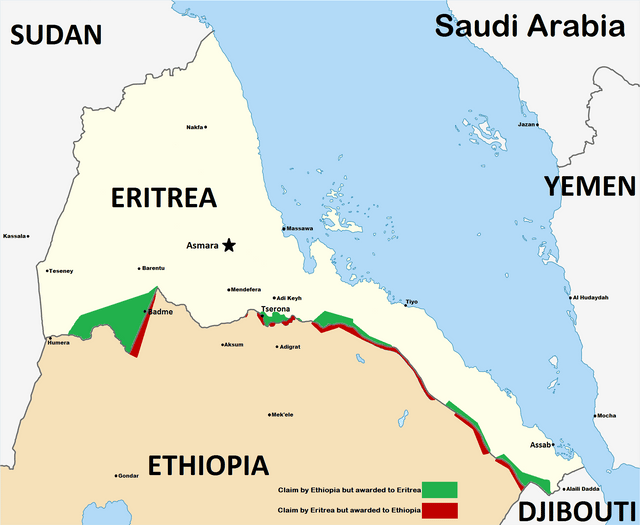

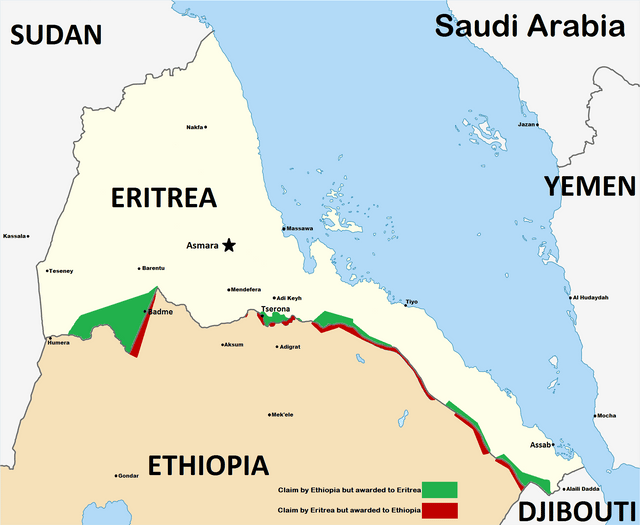

According to a ruling by an international commission in The Hague, Eritrea broke international law and triggered the war by invading Ethiopia.[35] At the end of the war, Ethiopia held all of the disputed territory and had advanced into Eritrea.[36] After the war ended, the Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission, a body founded by the UN, established that Badme, the disputed territory at the heart of the conflict, belongs to Eritrea.[37] As of 2019, Ethiopia still occupies the territory near Badme, including the town of Badme. On 5 June 2018, the ruling coalition of Ethiopia (Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front), headed by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, agreed to fully implement the peace treaty signed with Eritrea in 2000,[38] with peace declared by both parties in July 2018.[9]

| Eritrean–Ethiopian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

supported by: | supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 19,000 killed[17][18] Eritreans died (Eritrea claims) 67,000 died [19] Eritreans died (Eritrea claims ) 20,000–50,000[20] or 150,000[21] killed (other estimates) 5 MiG-29s 1 Aermacchi MB-339[22] | 34,000[23]–60,000[24] Ethiopians killed (Ethiopian claim) 123,000 Ethiopians died [25][26] (Ethiopian clandestine opposition claim) 150,000 Ethiopians died [21] (other estimates) 3 MiG-21s 1 MiG-23 1 Su-25 2+ Mi-35s[27] | ||||||||

Background

From 1961 until 1991, Eritrea had fought a long war of independence against Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Civil War began on 12 September 1974 when the Marxist Derg staged a coup d'état against Emperor Haile Selassie.[39] It lasted until 1991 when the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)—a coalition of rebel groups led by the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front (TPLF)—overthrew the Derg government and installed a transitional government in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa.[39] The Derg government had been weakened by their loss of support due to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe.[39]

During the civil war, the groups fighting the Derg government had a common enemy, so the TPLF allied itself with the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF). In 1991 as part of the United Nations-facilitated transition of power to the transitional government, it was agreed that the EPLF should set up an autonomous transitional government in Eritrea and that a referendum would be held in Eritrea to find out if Eritreans wanted to secede from Ethiopia. The referendum was held and the vote was overwhelmingly in favour of independence. In April 1993 independence was achieved and the new state joined the United Nations.[10][40][41]

In 1991, the EPLF-backed transitional government of Eritrea and the TPLF-backed transitional government of Ethiopia agreed to set up a commission to look into any problems that arose between the two former wartime allies over the foreseen independence of Eritrea.[42] This commission was not successful, and during the following years relations between the governments of the two sovereign states deteriorated.[40]

Determining the border between the two states became a major conflict, and in November 1997 a border committee was set up to try to resolve that specific dispute. After federation and before independence, the line of the border had been of minor importance because it was only a demarcation line between federated provinces, and initially the two governments tacitly agreed that the border should remain as it had been immediately before independence. However, upon independence the border became an international frontier, and the two governments could not agree on the line that the border should take along its entire length,[40] and they looked back to the colonial period treaties between Italy and Ethiopia for a basis in international law for the precise line of the frontier between the states. Problems then arose because they could not agree on the interpretation of those agreements and treaties,[43] and it was not clear under international law how binding colonial treaties were on the two states.[44][45]

Writing after the war had finished, Jon Abbink postulated that President Isaias Afewerki of Eritrea, realising that his influence over the government in Ethiopia was slipping and given that "the facts on the ground, in the absence of a concrete border being marked—which anyhow lost much of its relevance after 1962 when Eritrea was absorbed by Ethiopia—have eminent relevance to any borderline decision of today" calculated that Eritrea could annex Badme.[46][47] If successful, this acquisition could be have been used to enhance his reputation and help maintain Eritrea's privileged economic relationship with Ethiopia. However, because Badme was in the province of Tigray, the region from which many of the members of the Ethiopian government originated (including Meles Zenawi, the former Ethiopian prime minister), the Ethiopian government came under political pressure from within the EPRDF as well as from the wider Ethiopian public to meet force with force.[46]

War

Chronology

After a series of armed incidents in which several Eritrean officials were killed near Badme,[48] on 6 May 1998,[49] a large Eritrean mechanized force entered the Badme region along the border of Eritrea and Ethiopia's northern Tigray Region, resulting in a firefight between the Eritrean soldiers and the Tigrayan militia and security police they encountered.[48][50][51]

On 13 May 1998 Ethiopia, in what Eritrean radio described as a "total war" policy, mobilized its forces for a full assault against Eritrea.[52] The Claims Commission found that this was in essence an affirmation of the existence of a state of war between belligerents, not a declaration of war, and that Ethiopia also notified the United Nations Security Council, as required under Article 51 of the UN Charter.[53]

The fighting quickly escalated to exchanges of artillery and tank fire, leading to four weeks of intense fighting. Ground troops fought on three fronts. On 5 June 1998, the Ethiopians launched air attacks on the airport in Asmara and the Eritreans retaliated by attacking the airport of Mekele. These raids caused civilian casualties and deaths on both sides of the border.[54][55][56] The United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1177 condemning the use of force and welcomed statements from both sides to end the air strikes.

There was then a lull as both sides mobilized huge forces along their common border and dug extensive trenches.[57] Both countries spent several hundred million dollars on new military equipment.[31] This was despite the peace mediation efforts by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and the US/Rwanda peace plan that was in the works. The US/Rwanda proposal was a four-point peace plan that called for withdrawal of both forces to pre-June 1998 positions. Eritrea refused, and instead demanded the demilitarization of all disputed areas along the common border, to be overseen by a neutral monitoring force, and direct talks.[58][59]

With Eritrea's refusal to accept the US/Rwanda peace plan, on 22 February 1999 Ethiopia launched a massive military offensive to recapture Badme. Tension had been high since 6 February 1999, when Ethiopia claimed that Eritrea had violated the moratorium on air raids by bombing Adigrat, a claim it later withdrew.[60] Surveying the extensive trenches the Eritreans had constructed, Ethiopian General Samora Yunis observed, "The Eritreans are good at digging trenches and we are good at converting trenches into graves. They, too, know this. We know each other very well".[61]

Following the first five days of heavy fighting at Badme, by which time Ethiopian forces had broken through Eritrea's fortified front and was 10 kilometers (six miles) deep into Eritrean territory, Eritrea accepted the OAU peace plan on 27 February 1999.[62][63] While both states said that they accepted the OAU peace plan, Ethiopia did not immediately stop its advance because it demanded that peace talks be contingent on an Eritrean withdrawal from territory occupied since the first outbreak of fighting.[64]

On 16 May the BBC reported that, after a lull of two weeks, the Ethiopians had attacked at Velessa on the Tsorona front-line, south of Eritrea's capital Asmara and that after two days of heavy fighting the Eritreans had beaten back the attack claiming to have destroyed more than forty-five Ethiopian tanks; although not able to verify the claim, which the Ethiopian Government dismissed as ridiculous, the BBC reporter did see more than 300 dead Ethiopians and more than 20 destroyed Ethiopian tanks.[65] In June 1999 the fighting continued with both sides in entrenched positions.[66] About a quarter of Eritrean soldiers were women.[67]

"Proximity talks" broke down in early May 2000 "with Ethiopia accusing Eritrea of imposing unacceptable conditions".[68][69] On 12 May the Ethiopians launched an offensive that broke through the Eritrean lines between Shambuko and Mendefera, crossed the Mareb River, and cut the road between Barentu and Mendefera, the main supply line for Eritrean troops on the western front of the fighting.[70][71]

Ethiopian sources state that on 16 May Ethiopian aircraft all returned to their bases after attacking targets between Areza and Maidema, and between Barentu and Omohager, while heavy ground fighting continued in the Dass and Barentu area and in Maidema. The next day Ethiopian ground forces with air support captured Das. Eritrean forces evacuated Barentu and fighting continued in Maidema.[72] Also on 17 May, due to the continuing hostilities, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1298 imposing an arms embargo on both countries.[73]

By 23 May Ethiopia claimed that its "troops had seized vital command posts in the heavily defended Zalambessa area, about 100 km (60 mi) south of the Eritrean capital, Asmara".[69] But the Eritreans claimed they withdrew from the disputed border town of Zalambessa and other disputed areas on the central front as a "'goodwill' gesture to revive peace talks"[74] while Eritrea claimed it was a 'tactical retreat' to take away one of Ethiopia's last remaining excuses for continuing the war;[75] a report from Chatham House observes, "the scale of Eritrean defeat was apparent when Eritrea unexpectedly accepted the OAU peace framework."[76] Having recaptured most of the contested territories—and having heard that the Eritrean government would withdraw from any other territories it occupied at the start of fighting in accordance with a request from the OAU—on 25 May 2000, Ethiopia declared the war was over.[7][77][78] By the end of May 2000, Ethiopia occupied about a quarter of Eritrea's territory, displacing 650,000 people[79] and destroying key components of Eritrea's infrastructure.

The widespread use of trenches has resulted in comparisons of the conflict to the trench warfare of World War I.[57] According to some reports, trench warfare led to the loss of "thousands of young lives in human-wave assaults on Eritrea's positions".[80] The Eritrean defences were eventually overtaken by a surprise Ethiopian pincer movement on the Western front, attacking a mined, but lightly defended mountain (without trenches), resulting in the capture of Barentu and an Eritrean retreat. The element of surprise in the attack involved the use of donkeys as pack animals as well as being a solely infantry affair, with tanks coming in afterwards only to secure the area.[81]

Regional destabilisation

The fighting also spread to Somalia as both governments tried to outflank one another. The Eritrean government began supporting the Oromo Liberation Front,[82] a rebel group seeking independence of Oromia from Ethiopia that was based in a part of Somalia controlled by Mohamed Farrah Aidid.[83] Ethiopia retaliated by supporting groups in southern Somalia who were opposed to Aidid, and by renewing relations with the Islamic regime in Sudan—which is accused of supporting the Eritrean Islamic Salvation, a Sudan-based group that had launched attacks in the Eritrea–Sudan border region—while also lending support to various Eritrean rebel groups including a group known as the Eritrean Islamic Jihad.[84][85]

Casualties, displacement and economic disruption

Eritrea claimed that 19,000 Eritrean soldiers were killed during the conflict;[86] most reports put the total war casualties from both sides as being around 70,000.[29][87][88][89][90][91] All these figures have been contested and other news reports simply state that "tens of thousands" or "as many as 100,000" were killed in the war.[30][34] Eritrea accused Ethiopia of using "human waves" to defeat Eritrean trenches. But according to a report by The Independent, there were no "human waves" because Ethiopia instead outmaneuvered and overpowered the Eritrean trenches.[92]

The fighting led to massive internal displacement in both countries as civilians fled the war zone. Ethiopia expelled 77,000 Eritreans and Ethiopians of Eritrean origin it deemed a security risk, thus compounding Eritrea's refugee problem.[82][93][94] The majority of those were considered well off by the Ethiopian standard of living. They were deported after their belongings had been confiscated.[95] On the Eritrean side, around 7,500 Ethiopians living in Eritrea were interned, and thousands of others were deported. Thousands more remain in Eritrea, many of whom are unable to pay the 1,000 Birr tax on Ethiopians relocating to Ethiopia. According to Human Rights Watch, detainees on both sides were subject in some cases to torture, rape, or other degrading treatment.[96]

The economies of both countries were already weak as a result of decades of cold-war politics, civil war and drought. The war exacerbated these problems, resulting in food shortages. Prior to the war, much of Eritrea's trade was with Ethiopia, and much of Ethiopia's foreign trade relied on Eritrean roads and ports.[97]

Aftermath

Cessation of hostilities

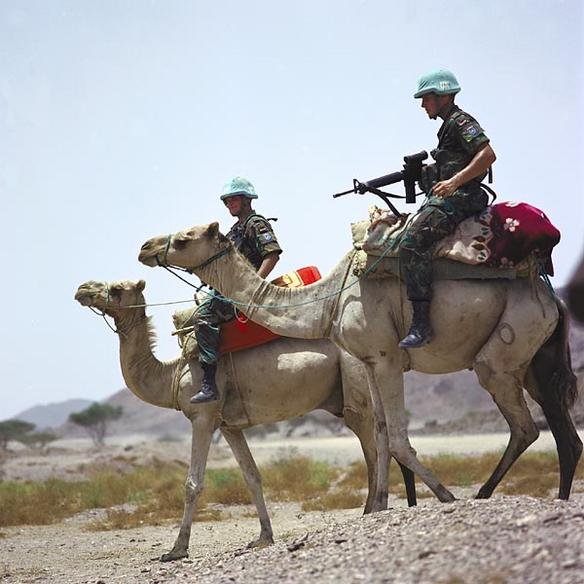

On 18 June 2000, the parties agreed to a comprehensive peace agreement and binding arbitration of their disputes under the Algiers Agreement. A 25-kilometer-wide Temporary Security Zone (TSZ) was established within Eritrea, patrolled by the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) from over 60 countries. On 12 December 2000 a peace agreement was signed by the two governments.[98]

Continued tensions

United Nations soldiers, part of the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea, monitoring Eritrea–Ethiopia boundary (2005).

On 13 April 2002, the Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission that was established under the Algiers Agreement in collaboration with Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague agreed upon a "final and binding" verdict. The ruling awarded some territory to each side, but Badme (the flash point of the conflict) was awarded to Eritrea.[99][100] Both countries vowed to accept the decision wholeheartedly the day after the ruling was made official.[101] A few months later Ethiopia requested clarifications, then stated it was deeply dissatisfied with the ruling.[102][103][104] In September 2003 Eritrea refused to agree to a new commission,[105] which they would have had to agree to if the old binding agreement was to be set aside,[99] and asked the international community to put pressure on Ethiopia to accept the ruling.[105] In November 2004, Ethiopia accepted the ruling "in principle".[106]

On 21 December 2005, a commission at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled that Eritrea broke international law when it attacked Ethiopia in 1998, triggering the broader conflict.[109]

Ethiopia and Eritrea subsequently remobilized troops along the border, leading to fears that the two countries could return to war.[110][111] On 7 December 2005, Eritrea banned UN helicopter flights and ordered Western members (particularly from the United States, Canada, Europe and Russia) of the UN peacekeeping mission on its border with Ethiopia to leave within 10 days, sparking concerns of further conflict with its neighbour.[112] In November 2006 Ethiopia and Eritrea boycotted an Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission meeting at The Hague which would have demarcated their disputed border using UN maps. Ethiopia was not there because it does not accept the decision and as it will not allow physical demarcation it will not accept map demarcation, and Eritrea was not there because although it backs the commission's proposals, it insists that the border should be physically marked out.[113]

Both nations have been accused of supporting dissidents and armed opposition groups against each other. John Young, a Canadian analyst and researcher for IRIN, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs news agency, reported that "the military victory of the EPRDF (Ethiopia) that ended the Ethiopia–Eritrea War, and its occupation of a swath of Eritrean territory, brought yet another change to the configuration of armed groups in the borderlands between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Asmara replaced Khartoum as the leading supporter of anti-EPRDF armed groups operating along the frontier".[114] However, Ethiopia is also accused of supporting rebels opposed to the Eritrean government.[115]

At the November 2007 deadline, some analysts feared the restart of the border war but the date passed without any conflict.[116] There were many reasons why war did not resume. Former U.S. Ambassador David Shinn said both Ethiopia and Eritrea were in a bad position. Many fear the weak Eritrean economy is not improving like those of other African nations while others say Ethiopia is bogged down in Mogadishu. David Shinn said Ethiopia has "a very powerful and so far disciplined national army that made pretty short work of the Eritreans in 2000 and the Eritreans have not forgotten that."[116] But he stated Ethiopia is not interested in war because America would condemn Ethiopia if it initiated the war saying "I don't think even the US could sit by and condone an Ethiopian initiated attack on Eritrea."[116]

Arbitration through the Permanent Court of Arbitration

As decided in the Algiers Agreement, the two parties presented their cases at the Permanent Court of Arbitration to two different Commissions:

In July 2001 the Commission sat to decide its jurisdiction, procedures and possible remedies. The result of this sitting was issued on August 2001. In October 2001, following consultations with the Parties, the Commission adopted its Rules of Procedure. In December 2001 the Parties filed their claims with the Commission. The claims filed by the Parties relate to such matters as the conduct of military operations in the front zones, the treatment of POWs and of civilians and their property, diplomatic immunities and the economic impact of certain government actions during the conflict. At the end of 2005 final awards have been issued on claims on Pensions, and Ports. Partial awards have been issued for claims about: Prisoners of War, the Central Front, Civilians Claims, the Western and Eastern Fronts, Diplomatic, Economic and property losses, and Jus Ad Bellum.

The Ethiopia–Eritrean claim committee ruled that:

- The areas initially invaded by Eritrean forces on that day [12 May 1998] were all either within undisputed Ethiopian territory or within territory that was peacefully administered by Ethiopia and that later would be on the Ethiopian side of the line to which Ethiopian armed forces were obligated to withdraw in 2000 under the Cease-Fire Agreement of 18 June 2000. In its Partial Award in Ethiopia’s Central Front Claims, the Commission held that the best available evidence of the areas effectively administered by Ethiopia in early May 1998 is that line to which they were obligated to withdraw in 2000. ...

- Consequently, the Commission holds that Eritrea violated Article 2, paragraph 4, of the Charter of the United Nations by resorting to armed force to attack and occupy Badme,

then under peaceful administration by Ethiopia, as well as other territory in the Tahtay Adiabo and Laelay Adiabo Weredas of Ethiopia, in an attack that began on 12 May 1998, and is liable to compensate Ethiopia, for the damages caused by that violation of international law.— Eritrea Ethiopia Claims Commission[120]

Christine Gray, in an article in the European Journal of International Law (2006), questioned the jurisdiction of the Commission making such an award, because "there were many factors which suggested that the Commission should have abstained from giving judgment". For example, the hearing of this claim, according to the Algiers agreement was to be heard by a separate commission and to be an investigation of exclusively factual concern not compensation.[121]

2018 Peace Agreement

The Ethiopian government under the leadership of new prime minister Abiy Ahmed unexpectedly announced on 5 June 2018 that it fully accepts the terms of the peace Algiers Agreement (2000). Ethiopia also announced that it would accept the outcome of the 2002 UN-backed Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) ruling which awarded disputed territories including the town of Badme to Eritrea.[122]

Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki noted the “positive signals”.

Eritrea Foreign Minister Osman Saleh led the first Eritrean deleagtion to Ethiopia in almost two decades when he visited Addis Ababa in late June 2018.[123]

At a summit in July 2018 in Asmara, Eritrea's President Isaias Afewerki and Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed signed a joint declaration formally ending the state of war between Ethiopia and Eritrea.[9][124] [125] Following the peace agreement, on July 18, 2018, after twenty years Ethiopian Airlines restarted its operations to Eritrea. Flight ET0312 left Bole International Airport to Asmara.[126][127]

Timeline: Continuing border conflicts

Eritrea (green) and Ethiopia (orange)

On 19 June 2008 the BBC published a time line (which they update periodically) of the conflict and reported that the "Border dispute rumbles on":

2007 September – War could resume between Ethiopia and Eritrea over their border conflict, warns United Nations special envoy to the Horn of Africa, Kjell Magne Bondevik. 2007 November – Eritrea accepts border line demarcated by international boundary commission. Ethiopia rejects it. 2008 January – UN extends mandate of peacekeepers on Ethiopia–Eritrea border for six months. UN Security Council demands Eritrea lift fuel restrictions imposed on UN peacekeepers at the Eritrea–Ethiopia border area. Eritrea declines, saying troops must leave border. 2008 February – UN begins pulling 1,700-strong peacekeeper force out due to lack of fuel supplies following Eritrean government restrictions. 2008 April – UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon warns of likelihood of new war between Ethiopia and Eritrea if peacekeeping mission withdraws completely. Outlines options for the future of the UN mission in the two countries. Djibouti accuses Eritrean troops of digging trenches at disputed Ras Doumeira border area and infiltrating Djiboutian territory. Eritrea denies charge. 2008 May – Eritrea calls on UN to terminate peacekeeping mission. 2008 June – Fighting breaks out between Eritrean and Djiboutian troops. 2016 June – Battle of Tsorona between Eritrean and Ethiopian troops— BBC[41]

In August 2009, Eritrea and Ethiopia were ordered to pay each other compensation for the war.[41]

In March 2011, Ethiopia accused Eritrea of sending bombers across the border. In April, Ethiopia acknowledged that it was supporting rebel groups inside Eritrea.[41] In July, a United Nations Monitoring Group accused Eritrea of being behind a plot to attack an African Union summit in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in January 2011. Eritrea stated the accusation was a total fabrication.[128]

In January 2012, five European tourists were killed and another two were kidnapped close to the border with Eritrea in the remote Afar Region in Ethiopia. In early March the kidnappers announced that they had released the two kidnapped Germans. On 15 March, Ethiopian ground forces attacked Eritrean military posts that they stated were bases in which Ethiopian rebels, including those involved in the January kidnappings, were trained by the Eritreans.[41][129]