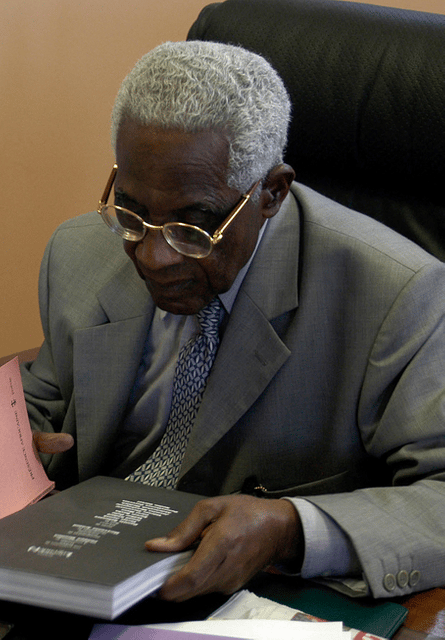

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire | |

|---|---|

| Born | Aimé Fernand David Césaire (1913-06-26)26 June 1913 Basse-Pointe, Martinique, France |

| Died | 17 April 2008(2008-04-17)(aged 94) Fort-de-France, Martinique, France |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure, University of Paris[1] |

| Known for | Poet, politician |

| Political party | Parti Progressiste Martiniquais |

| Spouse(s) | Suzanne Roussi |

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (/ɛmeɪ seɪˈzɛər/; French: [ɛme sezɛʁ]; 26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a Francophone and French poet, author and politician from the region of Martinique. He was "one of the founders of the négritude movement in Francophone literature".[2] His works included Une Tempête, a response to Shakespeare's play The Tempest, and Discours sur le colonialisme (Discourse on Colonialism), an essay describing the strife between the colonizers and the colonized. His works have been translated into many languages.

Aimé Fernand David Césaire | |

|---|---|

| Born | Aimé Fernand David Césaire (1913-06-26)26 June 1913 Basse-Pointe, Martinique, France |

| Died | 17 April 2008(2008-04-17)(aged 94) Fort-de-France, Martinique, France |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure, University of Paris[1] |

| Known for | Poet, politician |

| Political party | Parti Progressiste Martiniquais |

| Spouse(s) | Suzanne Roussi |

Student, educator and poet

Aimé Césaire was born in Basse-Pointe, Martinique, France, in 1913. His father was a tax inspector and his mother was a dressmaker. He was a lower class citizen but still learned to read and write. His family moved to the capital of Martinique, Fort-de-France, in order for Césaire to attend the only secondary school on the island, Lycée Schoelcher.[3] He considered himself of Igbo descent from Nigeria, and considered his first name Aimé a retention of an Igbo name; though the name is of French origin, ultimately from the Old French word amée, meaning beloved, its pronunciation is similar to the Igbo eme, which forms the basis for many Igbo given names.[4] Césaire traveled to Paris to attend the Lycée Louis-le-Grand on an educational scholarship. In Paris, he passed the entrance exam for the École Normale Supérieure in 1935 and created the literary review L'Étudiant noir (The Black Student) with Léopold Sédar Senghor and Léon Damas. Upon returning home to Martinique in 1936, Césaire began work on his long poem Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), a vivid and powerful depiction of the ambiguities of Caribbean life and culture in the New World.

Césaire married fellow Martinican student Suzanne Roussi in 1937. Together they moved back to Martinique in 1939 with their young son. Césaire became a teacher at the Lycée Schoelcher in Fort-de-France, where he taught Frantz Fanon, becoming a great influence for Fanon as both a mentor and contemporary. Césaire also served as an inspiration for, but did not teach, writer Édouard Glissant.

World War II

The years of World War II were ones of great intellectual activity for the Césaires. In 1941, Aimé Césaire and Suzanne Roussi founded the literary review Tropiques, with the help of other Martinican intellectuals such as René Ménil and Aristide Maugée, in order to challenge the cultural status quo and alienation that characterized Martinican identity at the time. Césaire's many run-ins with censorship did not deter him, however, from being an outspoken defendant of Martinican identity.[5] He also became close to French surrealist poet André Breton, who spent time in Martinique during the war. (The two had met in 1940, and Breton later would champion Cesaire's work.)[6]

In 1947, his book-length poem Cahier d'un retour au pays natal, which had first appeared in the Parisian periodical Volontés in 1939 after rejection by a French book publisher,[7] was published.[8] The book mixes poetry and prose to express Césaire's thoughts on the cultural identity of black Africans in a colonial setting. Breton contributed a laudatory introduction to this 1947 edition, saying that the "poem is nothing less than the greatest lyrical monument of our times."[9]

Political career

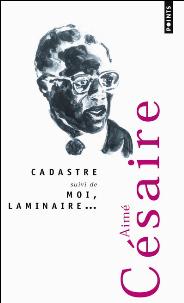

Cadastre (1961) and Moi, laminaire (1982)

In 1945, with the support of the French Communist Party (PCF), Césaire was elected mayor of Fort-de-France and deputy to the French National Assembly for Martinique. He was one of the principal drafters of the 1946 law on departmentalizing former colonies, a role for which pro-independence politicians have often criticized him.

Like many left-wing intellectuals in 1930s and 1940s France, Césaire looked toward the Soviet Union as a source of progress, virtue, and human rights. He later grew disillusioned with Communism, after the Soviet Union's 1956 suppression of the Hungarian revolution. He announced his resignation from the PCF in a text entitled Lettre à Maurice Thorez (Letter to Maurice Thorez). In 1958 Césaire founded the Parti Progressiste Martiniquais.

His writings during this period reflect his passion for civic and social engagement. He wrote Discours sur le colonialisme (Discourse on Colonialism), a denunciation of European colonial racism, decadence, and hypocrisy that was republished in the French review Présence Africaine in 1955 (English translation 1957). In 1960, he published Toussaint Louverture, based on the life of the Haitian revolutionary. In 1969, he published the first version of Une Tempête, a radical adaptation of Shakespeare's play The Tempest for a black audience.

Césaire served as President of the Regional Council of Martinique from 1983 to 1988. He retired from politics in 2001.

Later life

In 2006, he refused to meet the leader of the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), Nicolas Sarkozy, a probable contender at the time for the 2007 presidential election, because the UMP had voted for the 2005 French law on colonialism. This law required teachers and textbooks to "acknowledge and recognize in particular the positive role of the French presence abroad, especially in North Africa, a law considered by many as a eulogy to colonialism and French actions during the Algerian War. President Jacques Chirac finally had the controversial law repealed.

On 9 April 2008, Césaire had serious heart troubles and was admitted to Pierre Zobda Quitman hospital in Fort-de-France. He died on 17 April 2008.[10]

Césaire was accorded the honor of a state funeral, held at the Stade de Dillon in Fort-de-France on 20 April. French President Nicolas Sarkozy was present but did not make a speech. Pierre Aliker, who served for many years as deputy mayor under Césaire, gave the funeral oration.

Legacy

Martinique's airport at Le Lamentin was renamed Martinique Aimé Césaire International Airport on 15 January 2007. A national commemoration ceremony was held on 6 April 2011, as a plaque in Césaire's name was inaugurated in the Panthéon in Paris.[11]

Works

Each year links to its corresponding "[year] in poetry" article for poetry, or "[year] in literature" article for other works:

Poetry

1939: Cahier d'un retour au pays natal, Paris: Volontés, OCLC 213466273 [33] .

1946: Les armes miraculeuses, Paris: Gallimard, OCLC 248258485 [34] .

1947: Cahier d'un retour au pays natal, Paris: Bordas, OCLC 369684638 [35] .

1960: Ferrements, Paris: Editions du Seuil, OCLC 59034113 [38] .

1961: Cadastre, Paris: Editions du Seuil, OCLC 252242086 [39] .

1982: Moi, laminaire, Paris: Editions du Seuil, ISBN 978-2-02-006268-8.

1994: Comme un malentendu de salut ..., Paris: Editions du Seuil, ISBN 2-02-021232-3

Theatre

1958: Et les Chiens se taisaient, tragédie: arrangement théâtral. Paris: Présence Africaine; reprint: 1997.

1963: La Tragédie du roi Christophe. Paris: Présence Africaine; reprint: 1993; The Tragedy of King Christophe, New York: Grove, 1969.

1969: Une Tempête, adapted from The Tempest by William Shakespeare: adaptation pour un théâtre nègre. Paris: Seuil; reprint: 1997; A Tempest, New York: Ubu repertory, 1986.

1966: Une Saison au Congo. Paris: Seuil; reprint: 2001; A Season in the Congo, New York, 1968 (a play about Patrice Lumumba).

Other writings

"Poésie et connaissance", Tropiques (12): 158–70, January 1945.

Discours sur le colonialisme, Paris: Présence Africaine, 1955, OCLC 8230845 [40] .

Lettre à Maurice Thorez, Paris: Présence Africaine, 24 October 1956.[12]

Toussaint Louverture: La Révolution française et le problème colonial, Paris: Club français du livre, 1960, OCLC 263448333 [41] .

Discourse on Colonialism

Césaire’s "Discourse on Colonialism"[13] challenges the narrative of the colonizer and the colonized. This text criticizes the hypocrisy of justifying colonization with the equation "Christianity=civilized, paganism=savagery" (2) comparing white colonizers to "savages" (3). Césaire writes that "no one colonizes innocently, that no one colonizes with impunity either" concluding that "a nation which colonizes, that a civilization which justifies colonization - and therefore force - is already a sick civilization" (4). He condemns the colonizers, saying that though the men may not be inherently bad, the practice of colonization ruins them (2).

Césaire continues to deconstruct the colonizer, and ultimately concludes that by colonizing those white men often lose touch with who they were, and become brutalized into hidden instincts that result in the rape, torture, and race hatred that they put onto the people they colonize (2). He also examines the effects colonialism has on the colonized, stating that “colonization = ‘thing-ification’” (6), where because the colonizers are able to “other” the colonized, they can justify the means by which they colonize.

The text also continuously references Nazism, blaming the barbarism of colonialism and how whitewashed and accepted the tradition, for Hitler’s rise to power. He says that Hitler lives within and is the demon of "the very distinguished, very humanistic, very Christian bourgeois of the twentieth century."(3)

Césaire originally wrote his text in French in 1950, but later worked with Joan Pinkham to translate it to English. The translated version was published in 1972 (1).

See also

Créolité

Antillanité

Octave Mannoni