Perfume

Perfume

Perfume (UK: /ˈpɜːr.fjuːm/ US: /pərˈfjuːm/; French: parfum) is a mixture of fragrant essential oils or aroma compounds, fixatives and solvents, used to give the human body, animals, food, objects, and living-spaces an agreeable scent. It is usually in liquid form and used to give a pleasant scent to a persons body. Ancient texts and archaeological excavations show the use of perfumes in some of the earliest human civilizations. Modern perfumery began in the late 19th century with the commercial synthesis of aroma compounds such as vanillin or coumarin, which allowed for the composition of perfumes with smells previously unattainable solely from natural aromatics alone.

History

The word perfume derives from the Latin perfumare, meaning "to smoke through". Perfumery, as the art of making perfumes, began in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, and was further refined by the Romans and Persians.

The world's first-recorded chemist is considered a woman named Tapputi, a perfume maker mentioned in a cuneiform tablet from the 2nd millennium BC in Mesopotamia. She distilled flowers, oil, and calamus with other aromatics, then filtered and put them back in the still several times.

In India, perfume and perfumery existed in the Indus civilization (3300 BC – 1300 BC). One of the earliest distillations of Ittar was mentioned in the Hindu Ayurvedic text Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita

In 2003, archaeologists uncovered what are believed to be the world's oldest surviving perfumes in Pyrgos, Cyprus. The perfumes date back more than 4,000 years. They were discovered in an ancient perfumery, a 300-square-meter (3,230 sq ft) factory housing at least 60 stills, mixing bowls, funnels, and perfume bottles. In ancient times people used herbs and spices, such as almond, coriander, myrtle, conifer resin, and bergamot, as well as flowers.

In the 9th century the Arab chemist Al-Kindi (Alkindus) wrote the Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations, which contained more than a hundred recipes for fragrant oils, salves, aromatic waters, and substitutes or imitations of costly drugs. The book also described 107 methods and recipes for perfume-making and perfume-making equipment, such as the alembic (which still bears its Arabic name. [from Greek ἄμβιξ, "cup", "beaker"] described by Synesius in the 4th century ).

The Persian chemist Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna) introduced the process of extracting oils from flowers by means of distillation, the procedure most commonly used today. He first experimented with the rose. Until his discovery, liquid perfumes consisted of mixtures of oil and crushed herbs or petals, which made a strong blend. Rose water was more delicate, and immediately became popular. Both the raw ingredients and the distillation technology significantly influenced western perfumery and scientific developments, particularly chemistry.

The art of perfumery was known in western Europe from 1221, taking into account the monks' recipes of Santa Maria delle Vigne or Santa Maria Novella of Florence, Italy. In the east, the Hungarians produced in 1370 a perfume made of scented oils blended in an alcohol solution – best known as Hungary Water – at the behest of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary. The art of perfumery prospered in Renaissance Italy, and in the 16th century the personal perfumer to Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589), Rene the Florentine (Renato il fiorentino), took Italian refinements to France. His laboratory was connected with her apartments by a secret passageway, so that no formulae could be stolen en route. Thanks to Rene, France quickly became one of the European centers of perfume and cosmetics manufacture. Cultivation of flowers for their perfume essence, which had begun in the 14th century, grew into a major industry in the south of France.

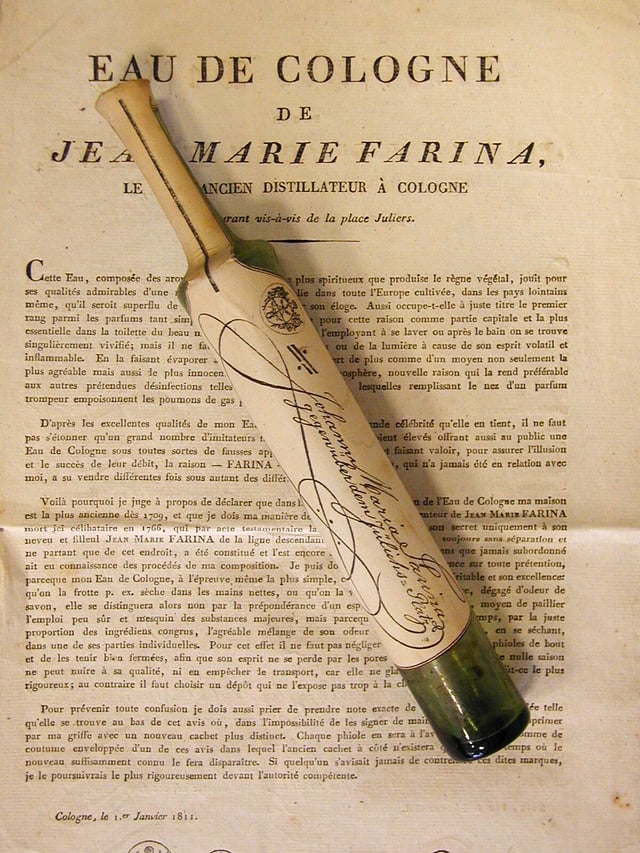

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, perfumes were used primarily by the wealthy to mask body odors resulting from infrequent bathing. Partly due to this patronage, the perfume industry developed. In 1693, Italian barber Giovanni Paolo Feminis created a perfume water called Aqua Admirabilis, today best known as eau de cologne; his nephew Johann Maria Farina (Giovanni Maria Farina) took over the business in 1732.

Dilution classes

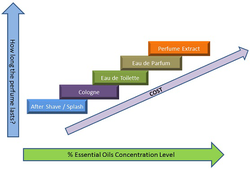

Perfume types reflect the concentration of aromatic compounds in a solvent, which in fine fragrance is typically ethanol or a mix of water and ethanol. Various sources differ considerably in the definitions of perfume types. The intensity and longevity of a perfume is based on the concentration, intensity and longevity of the aromatic compounds, or perfume oils, used. As the percentage of aromatic compounds increases, so does the intensity and longevity of the scent. Specific terms are used to describe a fragrance's approximate concentration by the percent of perfume oil in the volume of the final product. The most widespread terms are:

Parfum or extrait, in English known as perfume extract, pure perfume, or simply perfume: 15–40% (IFRA: typical ~20%) aromatic compounds

Esprit de Parfum (ESdP): 15–30% aromatic compounds, a seldom used strength concentration in between EdP and perfume

Eau de Parfum (EdP), Parfum de Toilette (PdT): 10–20% (typical ~15%) aromatic compounds, sometimes listed as "eau de perfume" or "millésime"; Parfum de Toilette is a less common term, most popular in the 1980s, that is generally analogous to Eau de Parfum

Eau de Toilette

Eau de Cologne

In addition to these widely seen concentrations, companies have marketed a variety of perfumed products under the name of "splashes," "mists," "veils" and other imprecise terms.

Generally these products contain 3% or less aromatic compounds.

There is much confusion over the term "cologne," which has three meanings.

The first and oldest definition refers to a family of fresh, citrus-based fragrances distilled using extracts from citrus, floral, and woody ingredients.

Supposedly these were first developed in the early 18th century in Cologne, Germany, hence the name. This type of "classical cologne" describes unisex compositions "which are basically citrus blends and do not have a perfume parent." Examples include Mäurer & Wirtz's 4711 (created in 1799), and Guerlain's Eau de Cologne Impériale (1853).

In the 20th century, the term took on a second meaning.

Fragrance companies began to offer lighter, less concentrated interpretations of their existing perfumes, making their products available to a wider range of customers.

Guerlain, for example, offered an Eau de Cologne version of its flagship perfume Shalimar . In contrast to classical colognes, this type of modern cologne is a lighter, diluted, less concentrated interpretation of a more concentrated product, typically a pure parfum. The cologne version is often the lightest concentration from a line of fragrance products.

Finally, the term "cologne" has entered the English language as a generic, overarching term to denote a fragrance worn by a man, regardless of its concentration.

The actual product worn by a man may technically be an eau de toilette, but he may still say that he "wears cologne."

A similar problem surrounds the term "perfume," which can be used a generic sense to refer to fragrances marketed to women, whether or not the fragrance is actually an extrait.

Classical colognes first appeared in Europe in the 17th century.

The first fragrance labeled a "parfum" extract with a high concentration of aromatic compounds was Guerlain's Jicky

Imprecise terminology

Original Eau de Cologne flacon 1811, from Johann Maria Farina, Farina gegenüber

The wide range in the percentages of aromatic compounds that may be present in each concentration means that the terminology of extrait, EdP, EdT, and EdC is quite imprecise.

Although an EdP will often be more concentrated than an EdT and in turn an EdC, this is not always the case.

Different perfumeries or perfume houses assign different amounts of oils to each of their perfumes.

Therefore, although the oil concentration of a perfume in EdP dilution will necessarily be higher than the same perfume in EdT from within a company's same range, the actual amounts vary among perfume houses.

An EdT from one house may have a higher concentration of aromatic compounds than an EdP from another.

Furthermore, some fragrances with the same product name but having a different concentration may not only differ in their dilutions, but actually use different perfume oil mixtures altogether. For instance, in order to make the EdT version of a fragrance brighter and fresher than its EdP, the EdT oil may be "tweaked" to contain slightly more top notes or fewer base notes. Chanel No. 5 is a good example: its parfum, EdP, EdT, and now-discontinued EdC concentrations are in fact different compositions (the parfum dates to 1921, whereas the EdP was not developed until the 1980s). In some cases, words such as extrême, intense, or concentrée that might indicate a higher aromatic concentration are actually completely different fragrances, related only because of a similar perfume accord. An example of this is Chanel's Pour Monsieur and Pour Monsieur Concentrée.

As a rule of thumb, women's fragrances tend to have higher levels of aromatic compounds than men's fragrances.

Fragrances marketed to men are typically sold as EdT or EdC, rarely as EdP or perfume extracts.

Women's fragrances used to be common in all levels of concentration, but today are mainly seen in parfum, EdP and EdT concentrations.

Solvent types

Perfume oils are often diluted with a solvent, though this is not always the case, and its necessity is disputed.

By far the most common solvent for perfume oil dilution is an alcohol solution typically a mixture of ethanol and water or a rectified spirit. Perfume oil can also be diluted by means of neutral-smelling oils such as fractionated coconut oil, or liquid waxes such as jojoba oil.

Applying fragrances

The conventional application of pure perfume (parfum extrait) in Western cultures is at pulse points, such as behind the ears, the nape of the neck, and the insides of wrists, elbows and knees, so that the pulse point will warm the perfume and release fragrance continuously.

According to perfumer Sophia Grojsman behind the knees is the ideal point to apply perfume in order that the scent may rise. The modern perfume industry encourages the practice of layering fragrance so that it is released in different intensities depending upon the time of the day. Lightly scented products such as bath oil, shower gel, and body lotion are recommended for the morning; eau de toilette is suggested for the afternoon; and perfume applied to the pulse points for evening. Cologne fragrance is released rapidly, lasting around 2 hours. Eau de toilette lasts from 2 to 4 hours, while perfume may last up to six hours.

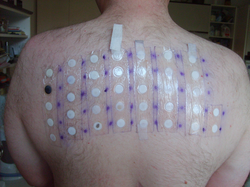

A variety of factors can influence how fragrance interacts with the wearer's own physiology and affect the perception of the fragrance.

Diet is one factor, as eating spicy and fatty foods can increase the intensity of a fragrance.

The use of medications can also impact the character of a fragrance.

The relative dryness of the wearer's skin is important, since dry skin will not hold fragrance as long as skin with more oil.

Describing a perfume

The precise formulae of commercial perfumes are kept secret. Even if they were widely published, they would be dominated by such complex ingredients and odorants that they would be of little use in providing a guide to the general consumer in description of the experience of a scent. Nonetheless, connoisseurs of perfume can become extremely skillful at identifying components and origins of scents in the same manner as wine experts.

The most practical way to start describing a perfume is according to the elements of the fragrance notes of the scent or the "family" it belongs to, all of which affect the overall impression of a perfume from first application to the last lingering hint of scent.

The trail of scent left behind by a person wearing perfume is called its sillage, after the French word for "wake", as in the trail left by a boat in water.

Fragrance notes

Perfume is described in a musical metaphor as having three sets of notes, making the harmonious scent accord. The notes unfold over time, with the immediate impression of the top note leading to the deeper middle notes, and the base notes gradually appearing as the final stage. These notes are created carefully with knowledge of the evaporation process of the perfume.

Top notes: Also called the head notes. The scents that are perceived immediately on application of a perfume. Top notes consist of small, light molecules that evaporate quickly. They form a person's initial impression of a perfume and thus are very important in the selling of a perfume. Examples of top notes include mint, lavender and coriander.

Middle notes: Also referred to as heart notes. The scent of a perfume that emerges just prior to the dissipation of the top note. The middle note compounds form the "heart" or main body of a perfume and act to mask the often unpleasant initial impression of base notes, which become more pleasant with time. Examples of middle notes include seawater, sandalwood and jasmine.

Base notes: The scent of a perfume that appears close to the departure of the middle notes. The base and middle notes together are the main theme of a perfume. Base notes bring depth and solidity to a perfume. Compounds of this class of scents are typically rich and "deep" and are usually not perceived until 30 minutes after application. Examples of base notes include tobacco, amber and musk.

The scents in the top and middle notes are influenced by the base notes, as well the scents of the base notes will be altered by the type of fragrance materials used as middle notes.

Manufacturers of perfumes usually publish perfume notes and typically they present it as fragrance pyramid, with the components listed in imaginative and abstract terms.

Olfactive families

Grouping perfumes can never be a completely objective or final process.

Many fragrances contain aspects of different families.

Even a perfume designated as "single flower", however subtle, will have undertones of other aromatics.

"True" unitary scents can rarely be found in perfumes as it requires the perfume to exist only as a singular aromatic material.

Classification by olfactive family is a starting point for a description of a perfume, but it cannot by itself denote the specific characteristic of that perfume.

Traditional

The traditional classification which emerged around 1900 comprised the following categories:

Single Floral: Fragrances that are dominated by a scent from one particular flower; in French called a soliflore. (e.g. Serge Lutens'Sa Majeste La Rose, which is dominated by rose.)

Floral Bouquet: Is a combination of fragrance of several flowers in a perfume compound. Examples include Quelques Fleurs by Houbigant and Joy by Jean Patou.

Amber or "Oriental": A large fragrance class featuring the sweet slightly animalic scents of ambergris or labdanum, often combined with vanilla, tonka bean, flowers and woods. Can be enhanced by camphorous oils and incense resins, which bring to mind Victorian era imagery of the Middle East and Far East. Traditional examples include Guerlain's Shalimar , Yves Saint Laurent's Opium and Chanel's Coco Mademoiselle.

Woody: Fragrances that are dominated by woody scents, typically of agarwood, sandalwood, cedarwood, and vetiver. Patchouli, with its camphoraceous smell, is commonly found in these perfumes. A traditional example here would be Myrurgia's Maderas De Oriente or Chanel Bois des Îles. A modern example would be Balenciaga Rumba.

Leather: A family of fragrances which features the scents of honey, tobacco, wood and wood tars in its middle or base notes and a scent that alludes to leather. Traditional examples include Robert Piguet's Bandit and Balmain's Jolie Madame.

Chypre ( IPA: [ʃipʁ] ): Meaning Cyprus in French, this includes fragrances built on a similar accord consisting of bergamot, oakmoss, and labdanum. This family of fragrances is named after the eponymous 1917 perfume by François Coty, and one of the most famous extant examples is Guerlain's Mitsouko

Fougère ( IPA: [fu.ʒɛʁ] ): Meaning fern in French, built on a base of lavender, coumarin and oakmoss. Houbigant's Fougère Royale pioneered the use of this base. Many men's fragrances belong to this family of fragrances, which is characterized by its sharp herbaceous and woody scent. Some well-known modern fougères are Fabergé Brut and Guy Laroche Drakkar Noir.

Modern

Since 1945, due to great advances in the technology of perfume creation (i.e., compound design and synthesis) as well as the natural development of styles and tastes, new categories have emerged to describe modern scents:

Bright Floral: combining the traditional Single Floral & Floral Bouquet categories. A good example would be Estée Lauder's Beautiful.

Green: a lighter and more modern interpretation of the Chypre type, with pronounced cut grass, crushed green leaf and cucumber-like scents. Examples include Estée Lauder's Aliage, Sisley's Eau de Campagne, and Calvin Klein's Eternity.

Aquatic, Oceanic, or Ozonic: the newest category in perfume history, first appearing in 1988 Davidoff Cool Water (1988), Christian Dior's Dune (1991), and many others. A clean smell reminiscent of the ocean, leading to many of the modern androgynous perfumes. Generally contains calone, a synthetic scent discovered in 1966, or other more recent synthetics. Also used to accent floral, oriental, and woody fragrances.

Citrus: An old fragrance family that until recently consisted mainly of "freshening" eau de colognes, due to the low tenacity of citrus scents. Development of newer fragrance compounds has allowed for the creation of primarily citrus fragrances. A good example here would be Faberge Brut.

Fruity: featuring the aromas of fruits other than citrus, such as peach, cassis (black currant), mango, passion fruit, and others. A modern example here would be Ginestet Botrytis.

Gourmand ( French: [ɡuʁmɑ̃] ): scents with "edible" or "dessert"-like qualities. These often contain notes like vanilla, tonka bean and coumarin, as well as synthetic components designed to resemble food flavors. A sweet example is Thierry Mugler's Angel.

Fragrance wheel

An original bottle of Fougère Royale by Houbigant. Created by Paul Parquet in 1884, it is one of the most important modern perfumes and inspired the eponymous Fougère class of fragrances.

The Fragrance wheel is a relatively new classification method that is widely used in retail and in the fragrance industry.

The method was created in 1983 by Michael Edwards, a consultant in the perfume industry, who designed his own scheme of fragrance classification. The new scheme was created in order to simplify fragrance classification and naming scheme, as well as to show the relationships between each of the individual classes.

The five standard families consist of Floral, Oriental, Woody, Aromatic Fougère, and Fresh, with the first four families borrowing from the classic terminology and the last consisting of newer bright and clean smelling citrus and oceanic fragrances that have arrived in the past generation due to improvements in fragrance technology. Each of the families are in turn divided into subgroups and arranged around a wheel. In this classification scheme, Chanel No.5, which is traditionally classified as an aldehydic floral, would be located under the Soft Floral sub-group, and amber scents would be placed within the Oriental group. As a class, chypre perfumes are more difficult to place since they would be located under parts of the Oriental and Woody families. For instance, Guerlain's Mitsouko is placed under Mossy Woods, but Hermès Rouge, a chypre with more floral character, would be placed under Floral Oriental.