Horner's method

Horner's method

In mathematics, the term Horner's rule (or Horner's method, Horner's scheme etc) refers to a polynomial evaluation method named after William George Horner expressed by

multiplications and

multiplications and additions. This is optimal, since there are polynomials of degreenthat cannot be evaluated with fewer arithmetic operations.

additions. This is optimal, since there are polynomials of degreenthat cannot be evaluated with fewer arithmetic operations.This algorithm is much older than Horner. He himself ascribed it to Joseph-Louis Lagrange but it can be traced back many hundreds of years to Chinese and Persian mathematicians.[1]

Horner's root-finding method: Until computers came into general use in about 1970 the term 'Horner's method' was used to refer to a root-finding method for polynomials named after Horner who described a similar method in 1819. This method was widely used and became a standard method for hand calculation. It gave a convenient way for using the Newton–Raphson method for polynomials. It relied on the algorithm for polynomial evaluation now named after Horner. After the introduction of computers this root-finding method went out of use and as a result the term Horner's method (rule etc) has become understood to mean just the polynomial evaluation algorithm.

Description of the algorithm

Given the polynomial

are constant coefficients, we wish to evaluate the polynomial at a specific value of

are constant coefficients, we wish to evaluate the polynomial at a specific value of that we'll call

that we'll call .

.To accomplish this, we define a new sequence of constants as follows:

is the value of

is the value of .

.To see why this works, note that the polynomial can be written in the form

into the expression,

into the expression,

Examples

for

for

We use synthetic division as follows:

on division by

on division by is 5.

is 5. . Thus

. Thus

we can see that

we can see that , the entries in the third row. So, synthetic division is based on Horner's method.

, the entries in the third row. So, synthetic division is based on Horner's method. on division by

on division by .

The remainder is 5. This makes Horner's method useful forpolynomial long division.

.

The remainder is 5. This makes Horner's method useful forpolynomial long division. by

by :

: .

. and

and . Divide

. Divide by

by using Horner's method.

using Horner's method.The third row is the sum of the first two rows, divided by 2. Each entry in the second row is the product of 1 with the third-row entry to the left. The answer is

Floating-point multiplication and division

, and

, and . Then, x (or x to some power) is repeatedly factored out. In thisbinary numeral system(base 2),

. Then, x (or x to some power) is repeatedly factored out. In thisbinary numeral system(base 2), , so powers of 2 are repeatedly factored out.

, so powers of 2 are repeatedly factored out.Example

For example, to find the product of two numbers (0.15625) and m:

Method

To find the product of two binary numbers d and m:

- A register holding the intermediate result is initialized to d.

- Begin with the least significant (rightmost) non-zero bit in m.

- 2b. Count (to the left) the number of bit positions to the next most significant non-zero bit. If there are no more-significant bits, then take the value of the current bit position.

- 2c. Using that value, perform a left-shift operation by that number of bits on the register holding the intermediate result

- If all the non-zero bits were counted, then the intermediate result register now holds the final result. Otherwise, add d to the intermediate result, and continue in step 2 with the next most significant bit in m.

Derivation

) the product is

) the product is

At this stage in the algorithm, it is required that terms with zero-valued coefficients are dropped, so that only binary coefficients equal to one are counted, thus the problem of multiplication or division by zero is not an issue, despite this implication in the factored equation:

The denominators all equal one (or the term is absent), so this reduces to

or equivalently (as consistent with the "method" described above)

In binary (base-2) math, multiplication by a power of 2 is merely a register shift operation. Thus, multiplying by 2 is calculated in base-2 by an arithmetic shift. The factor (2−1) is a right arithmetic shift, a (0) results in no operation (since 20 = 1 is the multiplicative identity element), and a (21) results in a left arithmetic shift. The multiplication product can now be quickly calculated using only arithmetic shift operations, addition and subtraction.

The method is particularly fast on processors supporting a single-instruction shift-and-addition-accumulate. Compared to a C floating-point library, Horner's method sacrifices some accuracy, however it is nominally 13 times faster (16 times faster when the "canonical signed digit" (CSD) form is used) and uses only 20% of the code space.[2]

Polynomial root finding

of degree

of degree with zeros

with zeros make some initial guess

make some initial guess such that

such that . Now iterate the following two steps:

. Now iterate the following two steps:- Using

of

of using the guess

using the guess .

.- Using Horner's method, divide out

to obtain

to obtain . Return to step 1 but use the polynomial

. Return to step 1 but use the polynomial and the initial guess

and the initial guess .

.These two steps are repeated until all real zeros are found for the polynomial. If the approximated zeros are not precise enough, the obtained values can be used as initial guesses for Newton's method but using the full polynomial rather than the reduced polynomials.[3]

Example

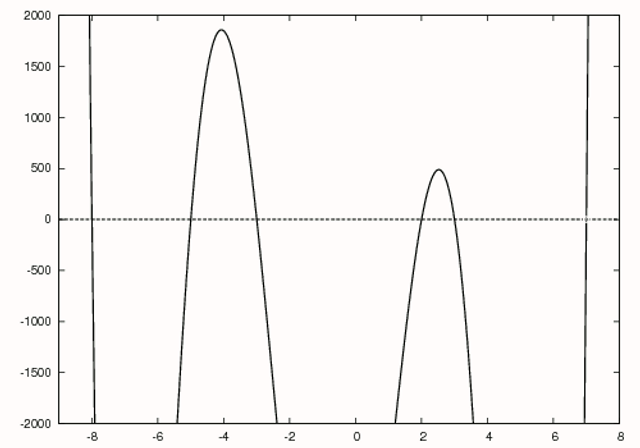

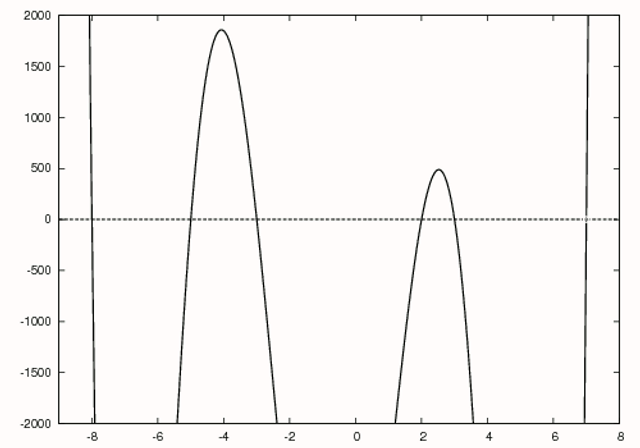

Consider the polynomial

which can be expanded to

is divided by

is divided by to obtain

to obtain

to obtain

to obtain

which is shown in yellow. The zero for this polynomial is found at 2 again using Newton's method and is circled in yellow. Horner's method is now used to obtain

which is shown in green and found to have a zero at −3. This polynomial is further reduced to

and solving the linear equation. As can be seen, the expected roots of −8, −5, −3, 2, 3, and 7 were found.

and solving the linear equation. As can be seen, the expected roots of −8, −5, −3, 2, 3, and 7 were found.Application

instead of n multiplies are needed (at the expense of requiring more storage) using the 1973 method of Paterson and Stockmeyer.[4]

instead of n multiplies are needed (at the expense of requiring more storage) using the 1973 method of Paterson and Stockmeyer.[4]Efficiency

Evaluation using the monomial form of a degree-n polynomial requires at most n additions and (n2 + n)/2 multiplications, if powers are calculated by repeated multiplication and each monomial is evaluated individually. (This can be reduced to n additions and 2n − 1 multiplications by evaluating the powers of x iteratively.) If numerical data are represented in terms of digits (or bits), then the naive algorithm also entails storing approximately 2n times the number of bits of x (the evaluated polynomial has approximate magnitude xn, and one must also store xn itself). By contrast, Horner's method requires only n additions and n multiplications, and its storage requirements are only n times the number of bits of x. Alternatively, Horner's method can be computed with n fused multiply–adds. Horner's method can also be extended to evaluate the first k derivatives of the polynomial with kn additions and multiplications.[5]

Horner's method is optimal, in the sense that any algorithm to evaluate an arbitrary polynomial must use at least as many operations. Alexander Ostrowski proved in 1954 that the number of additions required is minimal.[6] Victor Pan proved in 1966 that the number of multiplications is minimal.[7] However, when x is a matrix, Horner's method is not optimal.

This assumes that the polynomial is evaluated in monomial form and no preconditioning of the representation is allowed, which makes sense if the polynomial is evaluated only once. However, if preconditioning is allowed and the polynomial is to be evaluated many times, then faster algorithms are possible. They involve a transformation of the representation of the polynomial. In general, a degree-n polynomial can be evaluated using only ⌊n/2⌋+2 multiplications and n additions.[8]

Parallel evaluation

A disadvantage of Horner's rule is that all of the operations are sequentially dependent, so it is not possible to take advantage of instruction level parallelism on modern computers. In most applications where the efficiency of polynomial evaluation matters, many low-order polynomials are evaluated simultaneously (for each pixel or polygon in computer graphics, or for each grid square in a numerical simulation), so it is not necessary to find parallelism within a single polynomial evaluation.

If, however, one is evaluating a single polynomial of very high order, it may be useful to break it up as follows:

More generally, the summation can be broken into k parts:

where the inner summations may be evaluated using separate parallel instances of Horner's method. This requires slightly more operations than the basic Horner's method, but allows k-way SIMD execution of most of them.

Divided difference of a polynomial

Given the polynomial (as before)

Given the polynomial (as before)

proceed as follows[9]

At completion, we have

and

and separately, particularly when

separately, particularly when . Substituting

. Substituting in this method gives

in this method gives , the derivative of

, the derivative of .

.History

Qin Jiushao's algorithm for solving the quadratic polynomial equationresult: x=840[10]

Horner's paper, titled "A new method of solving numerical equations of all orders, by continuous approximation",[11] was read before the Royal Society of London, at its meeting on July 1, 1819, with Davies Gilbert, Vice-President and Treasurer, in the chair; this was the final meeting [26] of the session before the Society adjourned for its Summer recess. When a sequel was read before the Society in 1823, it was again at the final meeting of the session. On both occasions, papers by James Ivory, FRS, were also read. In 1819, it was Horner's paper that got through to publication in the "Philosophical Transactions".[11] later in the year, Ivory's paper falling by the way, despite Ivory being a Fellow; in 1823, when a total of ten papers were read, fortunes as regards publication, were reversed. Gilbert, who had strong connections with the West of England and may have had social contact with Horner, resident as Horner was in Bristol and Bath, published his own survey [27] of Horner-type methods earlier in 1823.

Horner's paper in Part II of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London for 1819 was warmly and expansively welcomed by a reviewer [28] in the issue of The Monthly Review: or, Literary Journal for April, 1820; in comparison, a technical paper by Charles Babbage is dismissed curtly in this review. However, the reviewer noted that another, similar method had also recently been published by the architect and mathematical expositor, Peter Nicholson. This theme is developed in a further review [29] of some of Nicholson's books in the issue of The Monthly Review for December, 1820, which in turn ends with notice of the appearance of a booklet by Theophilus Holdred, from whom Nicholson acknowledges he obtained the gist of his approach in the first place, although claiming to have improved upon it. The sequence of reviews is concluded in the issue of The Monthly Review for September, 1821, with the reviewer [30] concluding that whereas Holdred was the first person to discover a direct and general practical solution of numerical equations, he had not reduced it to its simplest form by the time of Horner's publication, and saying that had Holdred published forty years earlier when he first discovered his method, his contribution could be more easily recognized. The reviewer is exceptionally well-informed, even having cited Horner's preparatory correspondence with Peter Barlow in 1818, seeking work of Budan. The Bodlean Library, Oxford has the Editor's annotated copy of The Monthly Review from which it is clear that the most active reviewer in mathematics in 1814 and 1815 (the last years for which this information has been published) was none other than Peter Barlow, one of the foremost specialists on approximation theory of the period, suggesting that it was Barlow, who wrote this sequence of reviews. As it also happened, Henry Atkinson, of Newcastle, devised a similar approximation scheme in 1809; he had consulted his fellow Geordie, Charles Hutton, another specialist and a senior colleague of Barlow at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, only to be advised that, while his work was publishable, it was unlikely to have much impact. J. R. Young, writing in the mid-1830s, concluded that Holdred's first method replicated Atkinson's while his improved method was only added to Holdred's booklet some months after its first appearance in 1820, when Horner's paper was already in circulation.

The feature of Horner's writing that most distinguishes it from his English contemporaries is the way he draws on the Continental literature, notably the work of Arbogast. The advocacy, as well as the detraction, of Horner's Method has this as an unspoken subtext. Quite how he gained that familiarity has not been determined. Horner is known to have made a close reading of John Bonneycastle's book on algebra. Bonneycastle recognizes that Arbogast has the general, combinatorial expression for the reversion of series, a project going back at least to Newton. But Bonneycastle's main purpose in mentioning Arbogast is not to praise him, but to observe that Arbogast's notation is incompatible with the approach he adopts. The gap in Horner's reading was the work of Paolo Ruffini, except that, as far as awareness of Ruffini goes, citations of Ruffini's work by authors, including medical authors, in Philosophical Transactions speak volumes, as there are none — Ruffini's name[12] only appears in 1814, recording a work he donated to the Royal Society. Ruffini might have done better if his work had appeared in French, as had Malfatti's Problem in the reformulation of Joseph Diez Gergonne, or had he written in French, as had Antonio Cagnoli, a source quoted by Bonneycastle on series reversion. (Today, Cagnoli is in the Italian Wikipedia, as shown, but has yet to make it into either French or English.)

Fuller[13] showed that the method in Horner's 1819 paper differs from what afterwards became known as "Horner's method" and that in consequence the priority for this method should go to Holdred (1920). This view may be compared with the remarks concerning the works of Horner and Holdred in the previous paragraph. Fuller also takes aim at Augustus De Morgan. Precocious though Augustus de Morgan was, he was not the reviewer for The Monthly Review, while several others — Thomas Stephens Davies, J. R. Young, Stephen Fenwick, T. T. Wilkinson — wrote Horner firmly into their records, not least Horner, as he published extensively up until the year of his death in 1837. His paper in 1819 was one that would have been difficult to miss. In contrast, the only other mathematical sighting of Holdred is a single named contribution to The Gentleman's Mathematical Companion, an answer to a problem.

It is questionable to what extent it was De Morgan's advocacy of Horner's priority in discovery[14][15] that led to "Horner's method" being so called in textbooks, but it is true that those suggesting this tend to know of Horner largely through intermediaries, of whom De Morgan made himself a prime example. However, this method qua method was known long before Horner. In reverse chronological order, Horner's method was already known to:

Isaac Newton in 1669 (but precise reference needed)

the Chinese mathematician Zhu Shijie in the 14th century[15]

the Chinese mathematician Qin Jiushao in his Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections in the 13th century

the Persian mathematician Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī in the 12th century (the first to use that method in a general case of cubic equation)[16]

the Chinese mathematician Jia Xian in the 11th century (Song dynasty)

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, a Chinese work of the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) edited by Liu Hui (fl. 3rd century).[17]

However, this observation on its own masks significant differences in conception and also, as noted with Ruffini's work, issues of accessibility.

Qin Jiushao, in his Shu Shu Jiu Zhang (Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections; 1247), presents a portfolio of methods of Horner-type for solving polynomial equations, which was based on earlier works of the 11th century Song dynasty mathematician Jia Xian; for example, one method is specifically suited to bi-quintics, of which Qin gives an instance, in keeping with the then Chinese custom of case studies. The first person writing in English to note the connection with Horner's method was Alexander Wylie, writing in The North China Herald in 1852; perhaps conflating and misconstruing different Chinese phrases, Wylie calls the method Harmoniously Alternating Evolution (which does not agree with his Chinese, linglong kaifang, not that at that date he uses pinyin), working the case of one of Qin's quartics and giving, for comparison, the working with Horner's method. Yoshio Mikami in Development of Mathematics in China and Japan published in Leipzig in 1913, gave a detailed description of Qin's method, using the quartic illustrated to the above right in a worked example; he wrote:

"... who can deny the fact of Horner's illustrious process being used in China at least nearly six long centuries earlier than in Europe ... We of course don't intend in any way to ascribe Horner's invention to a Chinese origin, but the lapse of time sufficiently makes it not altogether impossible that the Europeans could have known of the Chinese method in a direct or indirect way."[18]

However, as Mikami is also aware, it was not altogether impossible that a related work, Si Yuan Yu Jian (Jade Mirror of the Four Unknowns; 1303) by Zhu Shijie might make the shorter journey across to Japan, but seemingly it never did, although another work of Zhu, Suan Xue Qi Meng, had a seminal influence on the development of traditional mathematics in the Edo period, starting in the mid-1600s. Ulrich Libbrecht (at the time teaching in school, but subsequently a professor of comparative philosophy) gave a detailed description in his doctoral thesis of Qin's method, he concluded: It is obvious that this procedure is a Chinese invention ... the method was not known in India. He said, Fibonacci probably learned of it from Arabs, who perhaps borrowed from the Chinese.[19] Here, the problems is that there is no more evidence for this speculation than there is of the method being known in India. Of course, the extraction of square and cube roots along similar lines is already discussed by Liu Hui in connection with Problems IV.16 and 22 in Jiu Zhang Suan Shu, while Wang Xiaotong in the 7th century supposes his readers can solve cubics by an approximation method described in his book Jigu Suanjing.

See also

Clenshaw algorithm to evaluate polynomials in Chebyshev form

De Boor's algorithm to evaluate splines in B-spline form

De Casteljau's algorithm to evaluate polynomials in Bézier form

Estrin's scheme to facilitate parallelization on modern computer architectures

Lill's method to approximate roots graphically

Ruffini's rule to divide a polynomial by a binomial of the form x − r