Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano | |

|---|---|

| Born | 24 September 1501 Pavia |

| Died | 21 September 1576(1576-09-21)(aged 74) Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Pavia |

| Known for | Polymath, founder of various fields and inventor of several machines |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Science, maths, philosophy, and literature |

| Influences | Archimedes, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, Leonardo Fibonacci |

| Influenced | Blaise Pascal,[1] François Viète, Pierre de Fermat,[1] Isaac Newton, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, Maria Gaetana Agnesi, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Carl Friedrich Gauss |

Gerolamo (or Girolamo,[2] or Geronimo[3]) Cardano (Italian: [dʒeˈrɔlamo karˈdano]; French: Jérôme Cardan; Latin: Hieronymus Cardanus; 24 September 1501 – 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath, whose interests and proficiencies ranged from being a mathematician, physician, biologist, physicist, chemist, astrologer, astronomer, philosopher, writer, and gambler.[4] He was one of the most influential mathematicians of the Renaissance, and was one of the key figures in the foundation of probability and the earliest introducer of the binomial coefficients and the binomial theorem in the Western world. He wrote more than 200 works on science.[5]

Cardano partially invented and described several mechanical devices including the combination lock, the gimbal consisting of three concentric rings allowing a supported compass or gyroscope to rotate freely, and the Cardan shaft with universal joints, which allows the transmission of rotary motion at various angles and is used in vehicles to this day. He made significant contributions to hypocycloids, published in De proportionibus, in 1570. The generating circles of these hypocycloids were later named Cardano circles or cardanic circles and were used for the construction of the first high-speed printing presses.[6]

Today, he is well known for his achievements in algebra. He made the first systematic use of negative numbers in Europe, published with attribution the solutions of other mathematicians for the cubic and quartic equations, and acknowledged the existence of imaginary numbers.

Gerolamo Cardano | |

|---|---|

| Born | 24 September 1501 Pavia |

| Died | 21 September 1576(1576-09-21)(aged 74) Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Pavia |

| Known for | Polymath, founder of various fields and inventor of several machines |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Science, maths, philosophy, and literature |

| Influences | Archimedes, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, Leonardo Fibonacci |

| Influenced | Blaise Pascal,[1] François Viète, Pierre de Fermat,[1] Isaac Newton, Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, Maria Gaetana Agnesi, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Carl Friedrich Gauss |

Early life and education

De propria vita, 1821

He was born in Pavia, Lombardy, the illegitimate child of Fazio Cardano, a mathematically gifted jurist, lawyer, and close personal friend of Leonardo da Vinci. In his autobiography, Cardano wrote that his mother, Chiara Micheri, had taken "various abortive medicines" to terminate the pregnancy; he was "taken by violent means from my mother; I was almost dead." She was in labour for three days.[7] Shortly before his birth, his mother had to move from Milan to Pavia to escape the Plague; her three other children died from the disease.

After a depressing childhood, with frequent illnesses, including impotence, and the rough upbringing by his overbearing father, in 1520, Cardano entered the University of Pavia against his father's wish, who wanted his son to undertake studies of law, but Girolamo felt more attracted to philosophy and science. During the Italian War of 1521-6, however, the authorities in Pavia were forced to close the university in 1524.[8] Cardano resumed his studies at the University of Padua, where he graduated with a doctorate in medicine in 1525.[9] His eccentric and confrontational style did not earn him many friends and he had a difficult time finding work after his studies had ended. In 1525, Cardano repeatedly applied to the College of Physicians in Milan, but was not admitted owing to his combative reputation and illegitimate birth. However, he was consulted by many members of the College of Physicians due to his irrefutable intelligence.[10]

Early career as a physician

Cardano wanted to practice medicine in a large, rich city like Milan, but he was denied a license to practice, so he settled for the town of Saccolongo, where he practiced without a license. There, he married Lucia Banderini in 1531. Before her death in 1546, they had three children, Giovanni Battista (1534), Chiara (1537) and Aldo Urbano (1543).[7] Cardano later wrote that those were the happiest days of his life.

With the help of a few noblemen, Cardano obtained a teaching position in mathematics in Milan. Having finally received his medical license, he practiced mathematics and medicine simultaneously, treating a few influential patients in the process. Because of this, he became one of the most sought-after doctors in Milan. In fact, by 1536, he was able to quit his teaching position, although he was still interested in mathematics. His notability in the medical field was such that the aristocracy tried to lure him out of Milan. Cardano later wrote that he turned down offers from the kings of Denmark and France, and the Queen of Scotland.[11]

Mathematics

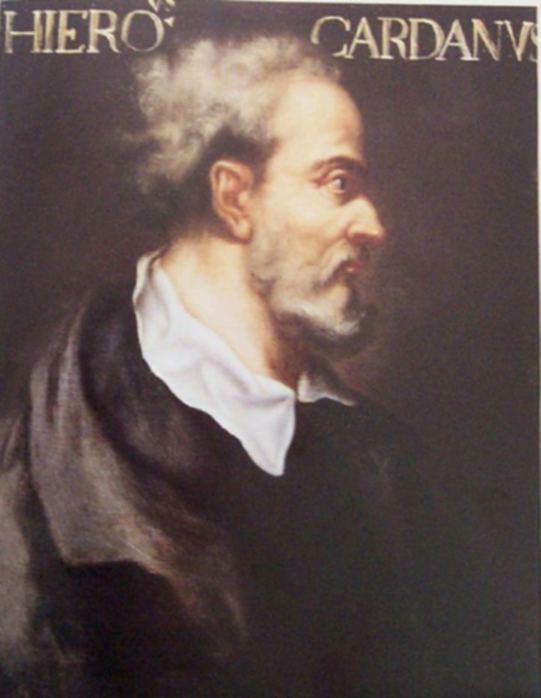

Portrait of Cardano on display at the School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews.

[13] (in modern notation), had been communicated to him in 1539 byNiccolò Fontana Tartaglia(who later claimed that Cardano had sworn not to reveal it, and engaged Cardano in a decade-long dispute) in the form of a poem,[14] but Ferro's solution predated Fontana's.[11] In his exposition, he acknowledged the existence of what are now calledimaginary numbers, although he did not understand their properties, described for the first time by his Italian contemporaryRafael Bombelli. In Opus novum de proportionibus he introduced thebinomial coefficientsand thebinomial theorem.

[13] (in modern notation), had been communicated to him in 1539 byNiccolò Fontana Tartaglia(who later claimed that Cardano had sworn not to reveal it, and engaged Cardano in a decade-long dispute) in the form of a poem,[14] but Ferro's solution predated Fontana's.[11] In his exposition, he acknowledged the existence of what are now calledimaginary numbers, although he did not understand their properties, described for the first time by his Italian contemporaryRafael Bombelli. In Opus novum de proportionibus he introduced thebinomial coefficientsand thebinomial theorem.Cardano was notoriously short of money and kept himself solvent by being an accomplished gambler and chess player. His book about games of chance, Liber de ludo aleae ("Book on Games of Chance"), written around 1564,[15] but not published until 1663, contains the first systematic treatment of probability,[16] as well as a section on effective cheating methods. He used the game of throwing dice to understand the basic concepts of probability. He demonstrated the efficacy of defining odds as the ratio of favourable to unfavourable outcomes (which implies that the probability of an event is given by the ratio of favourable outcomes to the total number of possible outcomes[17]). He was also aware of the multiplication rule for independent events but was not certain about what values should be multiplied.[18]

Other contributions

"Oneiron" ("Dream"), reverse of the medallion of Cardano by Leone Leoni, 1550-51.

Cardano's work with hypocycloids led him to the Cardan's Movement or Cardan Gear mechanism, in which a pair of gears with the smaller being one-half the size of the larger gear is used converting rotational motion to linear motion with greater efficiency and precision than a Scotch yoke, for example.[19] He is also credited with the invention of the Cardan suspension or gimbal.

Cardano made several contributions to hydrodynamics and held that perpetual motion is impossible, except in celestial bodies. He published two encyclopedias of natural science which contain a wide variety of inventions, facts, and occult superstitions. He also introduced the Cardan grille, a cryptographic writing tool, in 1550.

Someone also assigned to Cardano the credit for the invention of the so-called Cardano's Rings, also called Chinese Rings, but it is very probable that they predate Cardano.

Significantly, in the history of education of the deaf, he said that deaf people were capable of using their minds, argued for the importance of teaching them, and was one of the first to state that deaf people could learn to read and write without learning how to speak first. He was familiar with a report by Rudolph Agricola about a deaf mute who had learned to write.

De Subtilitate (1550)

As quoted from Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology:

The title of a work of Cardano's, published in 1552, De Subtilitate (corresponding to what would now be called transcendental philosophy), would lead us to expect, in the chapter on minerals, many far fetched theories characteristic of that age; but when treating of petrified shells, he decided that they clearly indicated the former sojourn of the sea upon the mountains.[20]

Later years and death

Medallion portrait of Cardano aged 49 by Leone Leoni (1509-1590)

Two of Cardano's children — Giovanni Battista and Aldo Urbano — came to ignoble ends. Giovanni Battista, Cardano's eldest and favorite son, was tried and beheaded in 1560 for poisoning his wife,[11] after he discovered that their three children were not his. Aldo Urbano was a gambler, who stole money from his father, and so Gerolamo disinherited him in 1569.

Cardano moved from Pavia to Bologna, in part because he believed that the decision to execute Giovanni was influenced by Gerolamo's battles with the academic establishment in Pavia, and his colleagues' jealousy at his scientific achievements and also because he was beset with allegations of sexual impropriety with his students.[7] Cardano was arrested by the Inquisition in 1570 for unknown reasons, and forced to spend several months in prison and abjure his professorship. He moved to Rome, and received a lifetime annuity from Pope Gregory XIII (after first having been rejected by Pope Pius V) and finished his autobiography. He was accepted in the Royal College of Physicians, and as well as practising medicine he continued his philosophical studies until his death in 1576.[5][7] Cardano is reported to have correctly predicted the exact date of his own death but it has been claimed that he achieved this by committing suicide.[11][21]

References in literature

The seventeenth century English physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne possessed the ten volumes of the Leyden 1663 edition of the complete works of Cardan in his library.[22]

Browne critically viewed Cardan as:

"that famous Physician of Milan, a great Enquirer of Truth, but too greedy a Receiver of it. He hath left many excellent Discourses, Medical, Natural, and Astrological; the most suspicious are those two he wrote by admonition in a dream, that is De Subtilitate & Varietate Rerum. Assuredly this learned man hath taken many things upon trust, and although examined some, hath let slip many others. He is of singular use unto a prudent Reader; but unto him that only desireth Hoties, or to replenish his head with varieties; like many others before related, either in the Original or confirmation, he may become no small occasion of Error."[23]

Richard Hinckley Allen tells of an amusing reference made by Samuel Butler in his book Hudibras:

Alessandro Manzoni's novel I Promessi Sposi portrays a pedantic scholar of the obsolete, Don Ferrante, as a great admirer of Cardano. Significantly, he values him only for his superstitious and astrological writings; his scientific writings are dismissed because they contradict Aristotle, but excused on the ground that the author of the astrological works deserves to be listened to even when he is wrong.

English novelist E. M. Forster's Abinger Harvest, a 1936 volume of essays, authorial reviews and a play, provides a sympathetic treatment of Cardano in the section titled 'The Past'. Forster believes Cardano was so absorbed in "self-analysis that he often forgot to repent of his bad temper, his stupidity, his licentiousness, and love of revenge" (212).

Works

De malo recentiorum medicorum medendi usu libellus, Hieronymus Scotus, Venice, 1536 (on medicine).[24]

Practica arithmetice et mensurandi singularis (on mathematics), Io. Antoninus Castellioneus/Bernadino Caluscho, Milan, 1539.[25]

De Consolatione, Libri tres, Hieronymus Scotus, Venice, 1542.[26] Translation into English by T. Bedingfield (1573).[27]

Libelli duo: De Supplemento Almanach; De Restitutione temporum et motuum coelestium; Item Geniturae LXVII insignes casibus et fortuna, cum expositione, Iohan. Petreius, Norimbergae, 1543.[28]

De Sapientia, Libri quinque, Iohan. Petreius, Norimbergae, 1544 (with De Consolatione reprint and De Libris Propriis, book I).[29]

De Immortalitate animorum, Henric Petreius, Nuremberg 1544/Sebastianus Gryphius, Lyons, 1545.[30]

Contradicentium medicorum (on medicine), Hieronymus Scotus, Venetijs, 1545.[31]

Artis magnae, sive de regulis algebraicis (on algebra: also known as Ars magna), Iohan. Petreius, Nuremberg, 1545.[32][33] Translation into English by D. Witmer (1968).[34]

Della Natura de Principii e Regole Musicale, ca 1546 (on music theory: in Italian): posthumously published.[35]

De Subtilitate rerum (on natural phenomena), Johann Petreius, Nuremberg, 1550 .[36] Translation into English by J.M. Forrester (2013).[37]

Metoposcopia libris tredecim, et octingentis faciei humanae eiconibus complexa (on physiognomy), written 1550 (published posthumously by Thomas Jolly, Paris (Lutetiae Parisiorum), 1658).[38]

In Cl. Ptolemaei Pelusiensis IIII, De Astrorum judiciis... libros commentaria: cum eiusdem De Genituris libro, Henrichus Petri, Basle, 1554.[39]

Geniturarum Exemplar (De Genituris liber, separate printing), Theobaldus Paganus, Lyons, 1555.[40]

Ars Curandi Parva (written c. 1556).[41]

De Libris propriis (about the books he has written, and his successes in medical work), Gulielmus Rouillius, Leiden, 1557.[42]

De Rerum varietate, Libri XVII (on natural phenomena); (Revised edition), Matthaeus Vincentius, Avignon 1558.[43] Also Basle, Henricus Petri, 1559.[44][45]

Actio prima in calumniatorem (reply to J.C. Scaliger), 1557.

De Utilitate ex adversis capienda, Libri IIII (on the uses of adversity), Henrich Petri, Basle, 1561.[46]

Theonoston, seu De Tranquilitate, 1561. (Opera, Vol. II).

Somniorum synesiorum omnis generis insomnia explicantes, Libri IIII (Book of Dreams: with other writings), Henricus Petri, Basle 1562.[47]

Neronis encomium, Basle, 1562.[48] Translation into English by A. Paratico (2012).[49]

De Providentia ex anni constitutione, Alexander Benaccius, Bononiae, 1563.[50]

De Methodo medendi, Paris, In Aedibus Rouillii, 1565.[51]

De Causis, signis ac locis morborum, Liber unus, Alexander Benatius, Bononiae, 1569.[52]

Commentarii in Hippocratis Coi Prognostica, Opus Divinum; Commentarii De Aere, aquis et locis opus, Henric Petrina Officina, Basel, 1568/1570.[53]

Opus novum, De Proportionibus numerorum, motuum, ponderum, sonorum, aliarumque rerum mensurandarum. Item de aliza regula, Henric Petrina, Basel, 1570.[54]

Opus novum, cunctis De Sanitate tuenda, Libri quattuor, Sebastian HenricPetri, Basle, 1569.[55]

De Vita propria, 1576 (autobiography).[56] Translation into English by J. Stoner (2002).[57]

Liber De Ludo aleae, ("On Casting the Die" - on probability): posthumously published.[58][59] Translation into English by S.H. Gould (1961).[60]

Proxeneta, seu De Prudentia Civili (posthumously published: Paulus Marceau, Geneva, 1630).[61]

Collected Works

(A chronological key to this edition is supplied by M. Fierz.[62])

Hieronymi Cardani Mediolanensis Opera Omnia, cura Carolii Sponii (Lugduni, Ioannis Antonii Huguetan and Marci Antonii Ravaud, 1663) (10 volumes, Latin): Volume 1: Philologica, Logica, Moralia (Internet Archive [91] ; another at Google [92] ; another at Google [93] ) Volume 2: Moralia Quaedam et Physica (Google [94] ) Volume 3: Physica (Google [95] ) Volume 4: Arithmetica, Geometrica, Musica (Google [96] ) Volume 5: Astronomica, Astrologica, Onirocritica (Internet Archive [97] ; another at Google [98] ) Volume 6: Medicinalium I (Google [99] ) Volume 7: Medicinalium II (Google [100] ) Volume 8: Medicinalium III (Google [101] ) Volume 9: Medicinalium IV (Google [102] ) Volume 10: Opuscula Miscellanea (Google [103] )

See also

Blow book - an early form of art or magic trick initially uncovered by Gerolamo Cardano

Negative numbers - the core of Cardano's major contributions to science and maths