Günter Grass

Günter Grass

Günter Grass | |

|---|---|

| Born | Günter Wilhelm Graß [1] (1927-10-16)16 October 1927 Danzig-Langfuhr, Free City of Danzig |

| Died | 13 April 2015(2015-04-13)(aged 87) Lübeck, Germany |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, playwright, sculptor, graphic designer |

| Language | German |

| Period | 1956–2013 |

| Literary movement | Vergangenheitsbewältigung |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Georg Büchner Prize 1965 Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature 1999 Prince of Asturias Awards 1999 |

| Signature |  |

He was born in the Free City of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland). As a teenager, he served as a drafted soldier from late 1944 in the Waffen-SS and was taken prisoner of war by US forces at the end of the war in May 1945. He was released in April 1946. Trained as a stonemason and sculptor, Grass began writing in the 1950s. In his fiction, he frequently returned to the Danzig of his childhood.

Grass is best known for his first novel, The Tin Drum (1959), a key text in European magic realism. It was the first book of his Danzig Trilogy, the other two being Cat and Mouse and Dog Years. His works are frequently considered to have a left-wing political dimension, and Grass was an active supporter of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The Tin Drum was adapted as a film of the same name, which won both the 1979 Palme d'Or and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In 1999, the Swedish Academy awarded him the Nobel Prize in Literature, praising him as a writer "whose frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history".[7]

Günter Grass | |

|---|---|

| Born | Günter Wilhelm Graß [1] (1927-10-16)16 October 1927 Danzig-Langfuhr, Free City of Danzig |

| Died | 13 April 2015(2015-04-13)(aged 87) Lübeck, Germany |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, playwright, sculptor, graphic designer |

| Language | German |

| Period | 1956–2013 |

| Literary movement | Vergangenheitsbewältigung |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Georg Büchner Prize 1965 Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature 1999 Prince of Asturias Awards 1999 |

| Signature |  |

Early life

Grass's childhood home in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland)

Grass was born in the Free City of Danzig on 16 October 1927, to Wilhelm Grass (1899–1979), a Lutheran Protestant of German origin, and Helene Grass (née Knoff, 1898–1954), a Roman Catholic of Kashubian-Polish origin.[8][9] He referred to himself as Kashubian.[10][11][12] Grass was raised a Catholic and served as an altar boy when he was a child.[13] His parents had a grocery store with an attached apartment in Danzig-Langfuhr (now Gdańsk-Wrzeszcz). He had a sister, Waltraud, born in 1930.[14]

Grass attended the Danzig gymnasium Conradinum. In 1943, at age 16, he became a Luftwaffenhelfer (Air Force "helper"). Soon thereafter, he was conscripted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst (National Labour Service). In November 1944, shortly after his 17th birthday, Grass volunteered for submarine service with Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine, "to get out of the confinement felt as a teenager in his parents' house", which he considered stuffy Catholic lower middle-class.[15][16]

The Navy refused him and he was instead called up for the 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg in late 1944.[17][18] Grass did not reveal until 2006 that he was drafted into the Waffen-SS at that time.[19] His unit functioned as a regular Panzer Division, and he served with them from February 1945 until he was wounded on 20 April 1945. He was captured in Marienbad (now Mariánské Lázně, Czech Republic) and sent to a U.S. prisoner-of-war camp in Bad Aibling, Bavaria.[20]

From 1946 to 1947, Grass worked in a mine and received training in stonemasonry. He studied sculpture and graphics at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. He also was a co-founder of Group 47, organized by Hans Werner Richter. Grass worked as a writer, graphic designer, and sculptor, travelling frequently. In 1953 he moved to West Berlin and studied at the Berlin University of the Arts. From 1960, he lived in Berlin as well as part-time in Schleswig-Holstein.[21] In 1961 he publicly objected to the erection of the Berlin Wall.

From 1983 to 1986, he held the presidency of the Academy of Arts, Berlin.[20]

Personal life

Grass's 1954 marriage to Anna Margareta Schwarz - a Swiss dancer - ended in divorce in 1978. He and Schwarz had four children: Franz (born 1957), Raoul (1957), Laura (1961), and Bruno (1965). Separated in 1972, he began a relationship with Veronika Schröter and had a child with her, Helene (1974). He also had a child with Ingrid Kruger, Nele (1979). In 1979 he married Ute Grunert, an organist, to whom he was still married at his death.[20] He had two stepsons from his second marriage, Malte and Hans. He had 18 grandchildren at his death.[20][22]

Grass was a fan of Bundesliga Club SC Freiburg.[23]

Major works

Danzig Trilogy

Danzig Krahntor waterfront (postcard, c. 1900)

Grass's best-known work is The Tin Drum (German: Die Blechtrommel), published in 1959 (and adapted as a film of the same name by director Volker Schlöndorff in 1979). It was followed in 1961 by Cat and Mouse (German: Katz und Maus), a novella, and in 1963 by the novel Dog Years (German: Hundejahre).

The books are collectively called the Danzig Trilogy and focus on the rise of Nazism and how World War II affected Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), which was separated from Germany after World War I and became the Free City of Danzig (German: Freie Stadt Danzig).[24] Dog Years (1965) is considered a sequel of sorts to The Tin Drum, as it features some of the same characters.[25] It portrays the area's mixed ethnicities and complex historical background in lyrical prose that is highly evocative.[26]

The Tin Drum established Grass as one of the leading authors of Germany, and also set a high bar of comparison for all of his subsequent works, which were often compared unfavorably to this early work by critics.[27] Nonetheless, in the West Germany of the late '50s and early '60s the book could be controversial, and its "immorality" prompted the city of Bremen to revoke a prize it had bestowed upon him.[20] When Grass received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1999 the Nobel Committee stated that the publication of The Tin Drum "was as if German literature had been granted a new beginning after decades of linguistic and moral destruction"[28]

The Flounder

The 1977 novel The Flounder (German: Der Butt) is based on the folktale of "The Fisherman and His Wife", and deals with the struggle between the sexes. It has been read as an anti-feminist novel, since in the novel the magical flounder of the folk tale, now representing male triumphalism and the patriarchy is caught by a group of 1970s feminists, who put it on trial. The book interrogates male-female relations from the past and the present through the relationship between the narrator and his wife, who as the wife in the folk tale, insatiably craves more.[29] In spite of the fact that the book could be read as a defense of women and a denouncement of male chauvinism, the book was harshly critiqued and rejected by feminists, partly due to its portrayal of violence, sexualization and objectification, and what the feminists perceived as male narcissism and gender essentialism.[30]

My Century and Crabwalk

The 1999 book My Century (German: Mein Jahrhundert) was an overview of the 20th-century's many brutal historic events, conveyed in short pieces, a mosaic of expression. In 2002, Grass returned to the forefront of world literature with Crabwalk (German: Im Krebsgang). This novella, one of whose main characters first appeared in Cat and Mouse, was Grass's most successful work in decades. It dealt with the events of a refugee ship, full of thousands of Germans, being sunk by a Russian submarine, killing most on board. It was one of a number of works since the late 20th century that have explored the victimization of Germans in World War II.[31]

Memoir trilogy

In 2006, Grass published the first volume in a trilogy of autobiographic memoirs. Titled Peeling the Onion (German: Beim Häuten der Zwiebel), it dealt with his childhood, war years, early efforts as a sculptor and poet, and finally his literary success with the publication of The Tin Drum. In a prepublication interview Grass for the first time revealed that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS, and not only a Flakhelfer (anti-aircraft assistant) as he had long said. On being asked what caused the need for public confession and revelation of his past in the book he answered: "It was a weight on me, my silence over all these years is one of the reasons I wrote the book. It had to come out in the end."[32]

The interview and the book caused critics to accuse him of hypocrisy for having hidden this part of his past, while simultaneously being a strong voice for ethics and morality in the public debate.[32] The book itself was also praised for its depictions of the German postwar generation and the social and moral development of a nation burdened simultaneously by destruction and a deep sense of guilt.[33] Throughout the memoir Grass plays with the frailty of memory, for which the layers of the onion are a metaphor. Grass second-guesses his own memories, throws his own autobiographical statements into doubt and questions whether the person inhabiting his past was really him. This struggle with memory comes to represent the struggle of the German people during the same period with Germany's Nazi past.[34]

Main themes and literary style

A main theme in Grass's work is World War II and its effects on Germany and the German people, including a critique of the forms of ideological reasoning that undergirded the Nazi regime. The place of the city of Danzig/Gdańsk and its ambiguous historical status in between Germany and Poland often stands as a symbol of the ambiguity between ethnic groups, also found in Grass's own heritage which includes both German and Slavic family members who fought on opposite sides of the war. His works also show a sustained concern for the marginal and marginalized subjects, such as Oskar Matzerath, the dwarf in The Tin Drum whose body was considered an aberration unworthy of life in the Nazi ideology, or with Roma and Sinti people who were also deemed impure and unworthy and subjected to eugenics and genocide.[35][36]

His literary style combines elements of magic realism, with a penchant for questioning and complicating questions of authorship by intermingling realistic autobiographical elements with unreliable narrators and fantastic events or happenings that creates irony or satirizes events to form social critiques.[37][38]

Reception by critics and colleagues

Grass's work has tended to divide the critics into those who have considered his experiments and style to be sublime and those who have found it to be tied down by his political posturing. Particularly American critics such as John Updike have found the mixture of politics and social critique in his works to diminish its artistic qualities.[39] In his various critiques of Grass's works, Updike wrote that Grass had been consumed by his "strenuous career as celebrity-author-artist-Socialist" and about one of his later novels that "he can't be bothered to write a novel; he just sends dispatches ... from the front lines of his engagement". Even if frequently critical of Grass, Updike considered him to be "one of the very, very few authors whose next novel one has no intention of missing".[40]

Grass's literary style has been widely influential. John Irving called Grass "simply the most original and versatile writer alive". And many have noted parallels between Irving's A Prayer for Owen Meany and The Tin Drum.[41] Similarly, Salman Rushdie has acknowledged a debt to Grass's work, particularly The Tin Drum, and many parallels to Grass's work have been pointed out in his own oeuvre.[42]

Social and political activism

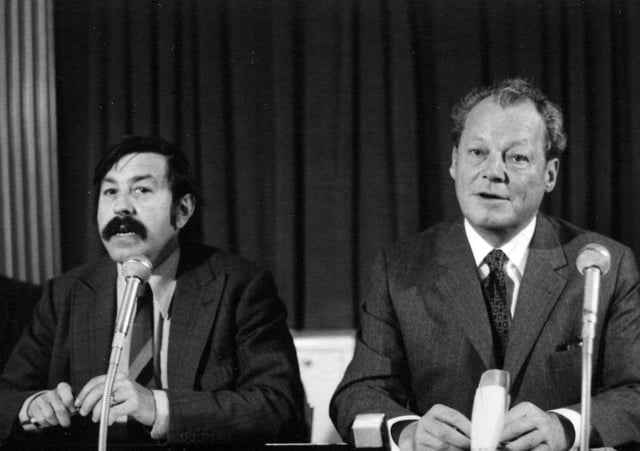

Grass in 1986

Grass was for several decades a supporter of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and its policies. He took part in German and international political debate on several occasions. During Willy Brandt's chancellorship, Grass was an active supporter. Grass criticised left-wing radicals and instead argued in favour of the "snail's pace", as he put it, of democratic reform (Aus dem Tagebuch einer Schnecke). Books containing his speeches and essays were released throughout his literary career.[20]

In the 1980s, he became active in the peace movement and visited Calcutta for six months.[20] A diary with drawings was published as Zunge zeigen, an allusion to Kali's tongue.

During the events leading up to the reunification of Germany in 1989–90, Grass argued for the continued separation of the two German states. He asserted that a unified Germany would be likely to resume its role as belligerent nation-state. This argument estranged many Germans, who came to see him as too much of a moralizing figure.[32]

On 4 April 2012, Grass's poem "What Must Be Said" (German: Was gesagt werden muss) was published in several European newspapers. Grass expressed his concern about the hypocrisy of German military support (the delivery of a submarine) for an Israel that might use such equipment to launch nuclear warheads against Iran, which "could wipe out the Iranian people". And he hoped that many would demand "that the governments of both Iran and Israel allow an international authority free and open inspection of the nuclear potential and capability of both." In response, Israel declared him persona non grata in that country.[45][46][47]

According to Avi Primor, president of the Israel Council on Foreign Relations, Grass was the only important German cultural figure who had refused to meet with him when he served as Israeli ambassador to Germany. Primor noted: "One explanation for [Grass']s strange behaviour might be found in the fact that Grass (who despite his poem is probably not the bitter enemy of Israel that one would imagine) had certain personal difficulties with Israel." Primor said that during Grass's earlier visit to Israel, he "was confronted with the anger of an Israeli public that booed him in successive public appearances. To be sure, the Israeli protestors were not targeting Grass personally and their anger had nothing at all to do with his literature. It was the German effort to establish cultural relations with Israel to which they objected. Grass, however, did not see it that way and may well have felt personally slighted."[48]

Grass was a supporter of the Campaign for the Establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, an organisation which campaigns for democratic reformation of the United Nations, and the creation of a more accountable international political system.[49]

On 26 April 2012, Grass wrote a poem criticizing European policy for the treatment of Greece in the European debt crisis. In "Europe's Disgrace", Grass accuses Europe of condemning Greece to poverty, a country "whose mind conceived Europe."[50][51]

Just a few days before he died Grass completed his last book, Vonne Endlichkait. The title is in East Prussian dialect, the native dialect of Grass, and it means "About Finitude." According to his publisher Gerhard Steidl, the book was "a literary experiment", combining short prose texts, poems and a pencil drawings by the writer.[52] The book was published in August 2015.

Awards and honours

Grass with the West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, 1972

Grass received dozens of international awards; in 1999, he was awarded the highest literary honour: the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy noted him as a writer "whose frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history".[7] His literature is commonly categorised as part of the German artistic movement known as Vergangenheitsbewältigung, roughly translated as "coming to terms with the past."

In 1965, Grass received the Georg Büchner Prize; in 1993 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[53] In 1995, he received the Hermann Kesten Prize.

Representatives of the city of Bremen joined together to establish the Günter Grass Foundation with the aim of establishing a centralized collection of his numerous works, especially his many personal readings, videos and films. The Günter Grass House in Lübeck houses exhibitions of his drawings and sculptures, an archive and a library.[54]

In 2012, Grass received the award European of the Year from the European Movement Denmark (Europabevægelsen) honoring his political debates in European affairs.[55]

Waffen-SS revelations

In August 2006, in an interview about his forthcoming book, Peeling the Onion, Grass said that he had been a member of the Waffen-SS in World War II.[19] Prior to that, he had been considered a typical member of the "Flakhelfer generation", one of those too young to see much fighting or to be involved with the Nazi regime beyond its youth organizations.[56]

On 15 August 2006, the online edition of Der Spiegel, Spiegel Online, published three 1946 documents from U.S. forces verifying Grass's Waffen-SS membership.[57]

After an unsuccessful attempt to volunteer for the U-boat fleet in 1942, at age 15, Grass was conscripted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service). He was called up for the Waffen-SS in 1944. Grass was trained as a tank gunner and fought with the 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg until its surrender to U.S. forces at Marienbad.[58][59]

In 2007, Grass published an account of his wartime experience in The New Yorker, including an attempt to "string together the circumstances that probably triggered and nourished my decision to enlist."[59] To the BBC, Grass said in 2006: "It happened as it did to many of my age. We were in the labour service and all at once, a year later, the call-up notice lay on the table. And only when I got to Dresden did I learn it was the Waffen-SS."[60]

Joachim Fest – German journalist, historian and biographer of Adolf Hitler – remarked, to the German weekly Der Spiegel, on Grass's disclosure: "After 60 years, this confession comes a bit too late. I can't understand how someone who for decades set himself up as a moral authority, a rather smug one, could pull this off.[61]

As Grass was for many decades an outspoken left-leaning critic of Germany's failure to deal with its Nazi past, his statement caused a great stir in the press. Rolf Hochhuth said it was "disgusting" that this same "politically correct" Grass had publicly criticized Helmut Kohl and Ronald Reagan's visit to a military cemetery at Bitburg in 1985, because it contained graves of Waffen-SS soldiers.[32] In the same vein, the historian Michael Wolffsohn accused Grass of hypocrisy in not earlier disclosing his SS membership.[62]

Others defended Grass, saying his involuntary Waffen-SS membership came very early in his life, resulting from his being drafted shortly after his seventeenth birthday. They noted he had always—after the war was lost—been publicly critical of Germany's Nazi past. For example, novelist John Irving criticised those who would dismiss the achievements of a lifetime because of a mistake made as a teenager.[63]

Grass's biographer Michael Jürgs described the controversy as resulting in "the end of a moral institution".[64] Lech Wałęsa initially criticized Grass for keeping silent about his Waffen-SS membership for 60 years. He later withdrew his criticism after reading Grass's letter to the mayor of Gdańsk, saying that Grass "set the good example for the others."[65] On 14 August 2006, the ruling party of Poland, Law and Justice, called on Grass to relinquish his honorary citizenship of Gdańsk. Jacek Kurski, a Law and Justice politician said, "It is unacceptable for a city where the first blood was shed, where World War II began, to have a Waffen-SS member as an honorary citizen."[66] But, according to a 2010 poll[67][68] ordered by city's authorities, the vast majority of Gdańsk citizens did not support Kurski's position. The mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz, said that he opposed submitting the affair to the municipal council because it was not for the council to judge history.[69]

Death

Grave of Günter Grass in Behlendorf

U.S. novelist John Irving delivered the main eulogy at a memorial service for Grass on 10 May in the Theater Lübeck. Among those who attended were German President Joachim Gauck, federal Commissioner for Culture Monika Grütters, and Paweł Adamowicz, mayor of Gdańsk.[73] Grütters, in remarks to mourners, noted that Grass through his work championed the independence of artists and of art itself.[74] Adamowicz said Grass had "bridged the chasm between Germany and Poland," and praised the novelist's "unwillingness to compromise."[75]