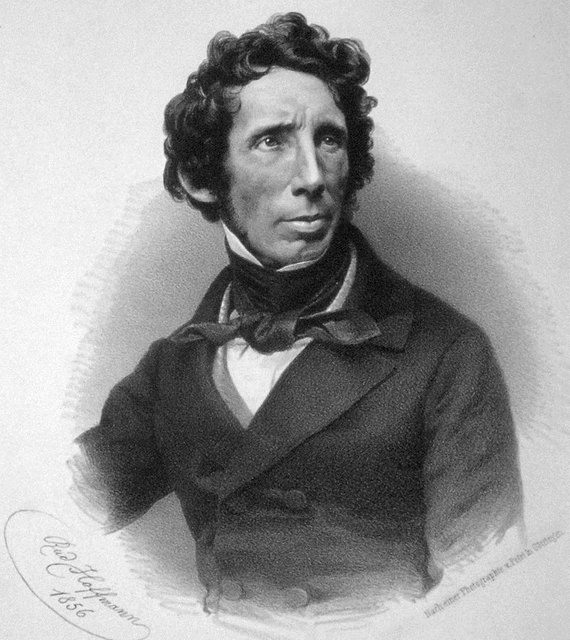

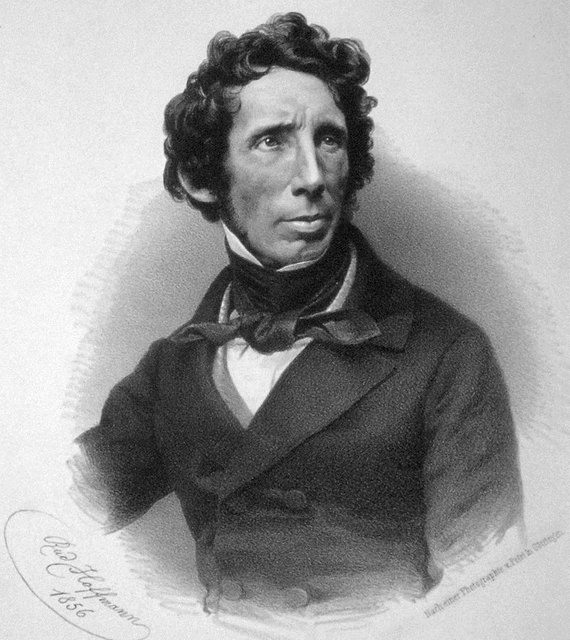

Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler | |

|---|---|

| Born | (1800-07-31)31 July 1800 Eschersheim, Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 23 September 1882(1882-09-23)(aged 82) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Wöhler synthesis of urea |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1872) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organic chemistry Biochemistry |

| Institutions | Polytechnic School in Berlin Polytechnic School at Kassel University of Göttingen |

| Doctoral advisor | Leopold Gmelin Jöns Jakob Berzelius |

| Doctoral students | Heinrich Limpricht Rudolph Fittig Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe Georg Ludwig Carius Albert Niemann Vojtěch Šafařík Carl Schmidt Theodor Zincke |

| Other notable students | Augustus Voelcker[1] Wilhelm Kühne |

Prof Friedrich Wöhler (German: [ˈvøːlɐ]) FRS(For) HFRSE (31 July 1800 – 23 September 1882) was a German chemist, best known for his synthesis of urea, but also the first to isolate several chemical elements, most notably titanium.

Friedrich Wöhler | |

|---|---|

| Born | (1800-07-31)31 July 1800 Eschersheim, Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 23 September 1882(1882-09-23)(aged 82) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Wöhler synthesis of urea |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1872) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organic chemistry Biochemistry |

| Institutions | Polytechnic School in Berlin Polytechnic School at Kassel University of Göttingen |

| Doctoral advisor | Leopold Gmelin Jöns Jakob Berzelius |

| Doctoral students | Heinrich Limpricht Rudolph Fittig Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe Georg Ludwig Carius Albert Niemann Vojtěch Šafařík Carl Schmidt Theodor Zincke |

| Other notable students | Augustus Voelcker[1] Wilhelm Kühne |

Biography

He was born in Eschersheim, which then belonged to Hanau, but is now a district of Frankfurt am Main. He was educated at the Frankfurt Gymnasium. His initial higher studies were at Marburg University in 1820.

In 1823 Wöhler finished his study of Medicine at Heidelberg University, having been taught in the laboratory of Leopold Gmelin, who then arranged for him to work under Jöns Jakob Berzelius in Stockholm, Sweden.

From 1826 to 1831 Wohler taught chemistry at the Polytechnic School in Berlin. In 1839 he was stationed at the Polytechnic School at Kassel. Afterwards, he became Ordinary Professor of Chemistry in the University of Göttingen, where he remained until his death in 1882. In 1834, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Contributions to chemistry

Wöhler is regarded as a pioneer in organic chemistry as a result of his (accidentally) synthesizing urea from ammonium cyanate in the Wöhler synthesis in 1828.[2] In a letter to Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius the same year, he wrote, 'In a manner of speaking, I can no longer hold my chemical water. I must tell you that I can make urea without the use of kidneys of any animal, be it man or dog.'[3]

This discovery has become celebrated as a refutation of vitalism, the hypothesis that living things are alive because of some special "vital force". However, contemporary accounts do not support that notion. This Wöhler Myth, as historian of science Peter J. Ramberg called it, originated from a popular history of chemistry published in 1931, which, "ignoring all pretense of historical accuracy, turned Wöhler into a crusader who made attempt after attempt to synthesize a natural product that would refute vitalism and lift the veil of ignorance, until 'one afternoon the miracle happened'".[4] Nevertheless, it was the beginning of the end of one popular vitalist hypothesis, that of Jöns Jakob Berzelius, that "organic" compounds could be made only by living things.

Major works, discoveries and research

Wöhler was also known for being a co-discoverer of beryllium, silicon and silicon nitride,[5] as well as the synthesis of calcium carbide, among others. In 1834, Wöhler and Justus Liebig published an investigation of the oil of bitter almonds. They proved by their experiments that a group of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms can behave like an element, take the place of an element, and be exchanged for elements in chemical compounds. Thus the foundation was laid of the doctrine of compound radicals, a doctrine which had a profound influence on the development of chemistry.

Wöhler was the first to isolate the elements yttrium, beryllium, and titanium, and to observe that "silicium" (silicon) can be obtained in crystals, and that some meteoric stones contain organic matter. He analyzed meteorites, and for many years wrote the digest on the literature of meteorites in the Jahresberichte über die Fortschritte der Chemie; he possessed the best private collection of meteoric stones and irons existing. Wöhler and Sainte Claire Deville discovered the crystalline form of boron, and Wöhler and Heinrich Buff discovered silane in 1856. Wöhler also prepared urea, a constituent of urine, from ammonium cyanate in the laboratory without the help of a living cell.

Final days and legacy

Wöhler's discoveries had great influence on the theory of chemistry. The journals of every year from 1820 to 1881 contain contributions from him. In the Scientific American supplement for 1882, it was remarked that "for two or three of his researches he deserves the highest honor a scientific man can obtain, but the sum of his work is absolutely overwhelming. Had he never lived, the aspect of chemistry would be very different from that it is now".[6]

Wöhler had several students who became notable chemists. Among them were Georg Ludwig Carius, Heinrich Limpricht, Rudolph Fittig, Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe, Albert Niemann, and Vojtěch Šafařík.

Family

He married twice: firstly in 1830 to Franziska Wohler (d.1832), and secondly in 1834 to Julie Pfeiffer.

Further works

Further works from Wöhler:

Lehrbuch der Chemie, Dresden, 1825, 4 vols.

Grundriss der Anorganischen Chemie, Berlin, 1830

Grundriss der Chemie, Berlin, 1837–1858 Vol.1&2 Digital edition [21] by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

Grundriss der Organischen Chemie, Berlin, 1840

Praktische Übungen in der Chemischen Analyse, Berlin, 1854

See also

Justus von Liebig

Silver cyanate

Silver fulminate

Isomerism

History of aluminium

Hilaire Marin Rouelle

Stanley Miller