France–United States relations

France–United States relations

France | United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| French Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Paris |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Gérard Araud | Chargé d'affaires Uzra Zeya |

The Statue of Liberty is a gift from the French people to the American people in memory of the Declaration of Independence.

French President Emmanuel Macron (left) and U.S. President Donald Trump (right) meet in Washington, April 2018.

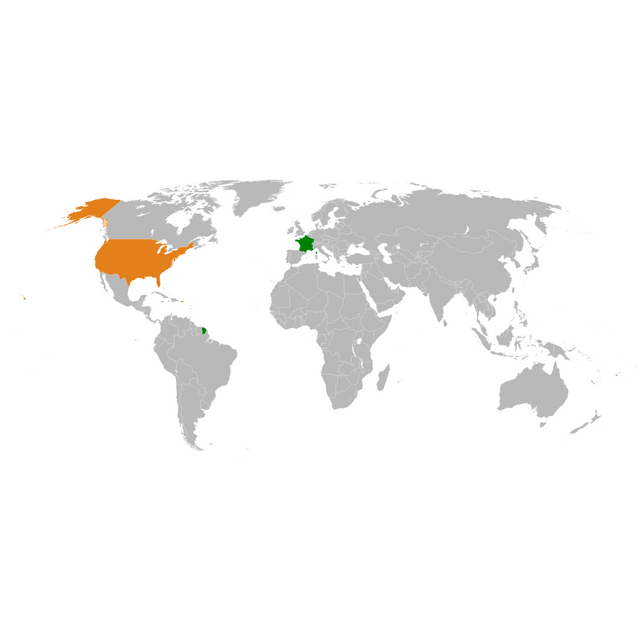

French–American relations refers to the diplomatic, social, economic and cultural relations between France and the United States since 1776. France was the first ally of the new United States. The 1778 treaty and military support proved decisive in the American victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War. France fared poorly, with few gains and heavy debts, which were contributing causes of France's own revolution and eventual transition to a Republic.

The American relationship with France has been peaceful except for the Quasi War in 1798-99, and fighting against Vichy France (while supporting Free France) during World War II. The relationship had always been important for both nations.

In the 21st Century, differences over the Iraq War led each country to have lowered favorability ratings of the other. However, since then, relations have improved, with American favorable ratings of France reaching a historic high of 87% in 2016.[1][2] Gallup concluded, "After diplomatic differences in 2003 soured relations between the two countries, France and the U.S. have found a common interest in combating international terrorism, and the mission has become personal for both countries."[2]

France | United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| French Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Paris |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Gérard Araud | Chargé d'affaires Uzra Zeya |

France and the American Revolution

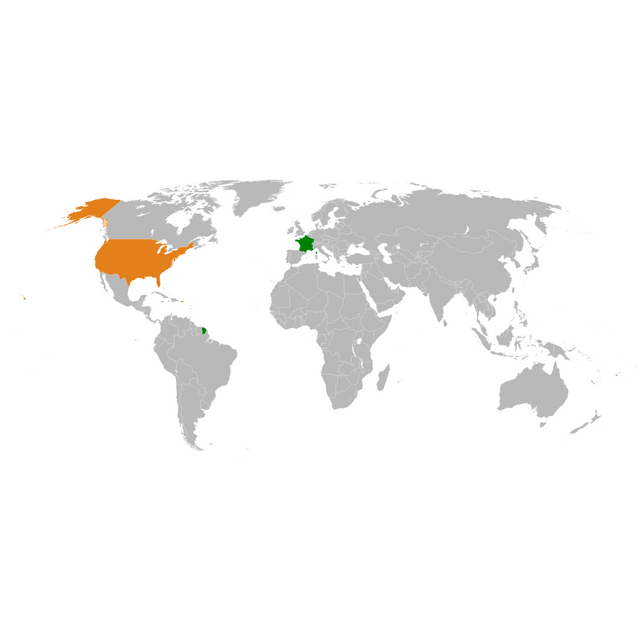

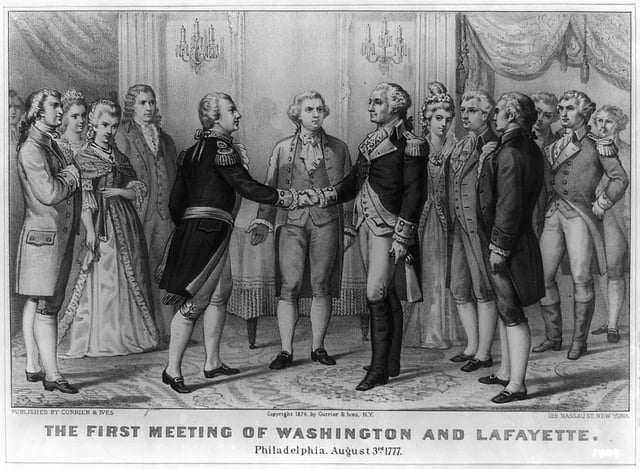

The Marquis de Lafayette visiting George Washington in 1777 during the American Revolutionary War.

The Battle of the Chesapeake where the French Navy defeated the Royal Navy in 1781

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis depicting the English surrendering to French (left) and American (right) troops.

As long as Great Britain and France remained at peace in Europe, and as long as the precarious balance in the American interior survived, British and French colonies coexisted without serious difficulty. However, beginning in earnest following the Glorious Revolution in England (1688), the simmering dynastic, religious, and factional rivalries between the Protestant British and Catholic French in both Europe and the Americas triggered four "French and Indian Wars" fought largely on American soil (King William's War, 1689–97; Queen Anne's War, 1702–13; King George's War, 1744–48; and, finally the Seven Years' War, 1756–63). Great Britain finally removed the French from continental North America in 1763 following French defeat in the Seven Years' War. Within a decade, the British colonies were in open revolt, and France retaliated by secretly supplying the independence movement with troops and war materials.

After Congress declared independence in July 1776, its agents in Paris recruited officers for the Continental Army, notably the Marquis de Lafayette, who served with distinction as a major general. Despite a lingering distrust of France, the agents also requested a formal alliance. After readying their fleet and being impressed by the U.S. victory at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, the French on February 6, 1778, concluded treaties of commerce and alliance that bound them to fight Britain until independence of the United States was assured.[3][4]

The military alliance began poorly. French Admiral d'Estaing sailed to North America with a fleet in 1778, and began a joint effort with American General John Sullivan to capture a British outpost at Newport, Rhode Island. D'Estaing broke off the operation to confront a British fleet, and then, despite pleas from Sullivan and Lafayette, sailed away to Boston for repairs. Without naval support, the plan collapsed, and American forces under Sullivan had to conduct a fighting retreat alone. American outrage was widespread, and several French sailors were killed in anti-French riots. D'Estaing's actions in a disastrous siege at Savannah, Georgia further undermined Franco-American relations.[5]

The alliance improved with the arrival in the United States in 1780 of the Comte de Rochambeau, who maintained a good working relationship with General Washington. French naval actions at the Battle of the Chesapeake made possible the decisive Franco–American victory at the siege of Yorktown in October 1781, effectively ending the war as far as the Americans were concerned. The French went on fighting, losing a naval battle to Britain in 1782.

The Patriot reliance on Catholic France for military, financial and diplomatic aid led to a sharp drop in anti-Catholic rhetoric. Indeed, the king replaced the pope as the demon patriots had to fight against. Anti-Catholicism remained strong among Loyalists, some of whom went to Canada after the war while most remained in the new nation. By the 1780s, Catholics were extended legal toleration in all of the New England states that previously had been so hostile. "In the midst of war and crisis, New Englanders gave up not only their allegiance to Britain but one of their most dearly held prejudices."[6]

Peace treaty

In the peace negotiations between the Americans and the British in Paris in 1782, the French played a major role. Indeed, the French Foreign Minister Vergennes had maneuvered so that the American Congress ordered its delegation to follow the advice of the French. However, the American commissioners, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and particularly John Jay, correctly realized that France did not want a strong United States. They realized that they would get better terms directly from Britain itself. The key episodes came in September, 1782, when Vergennes proposed a solution that was strongly opposed by the United States. France was exhausted by the war, and everyone wanted peace except Spain, which insisted on continuing the war until it captured Gibraltar from the British. Vergennes came up with the deal that Spain would accept instead of Gibraltar. The United States would gain its independence but be confined to the area east of the Appalachian Mountains. Britain would take the area north of the Ohio River. In the area south of that there would be set up an independent Indian state under Spanish control. It would be an Indian barrier state and keep the Americans from the Mississippi River or New Orleans, which were under Spanish control. John Jay promptly told the British that he was willing to negotiate directly with them, cutting off France and Spain. The British Prime Minister Lord Shelburne agreed. He was in full charge of the British negotiations and he now saw a chance to split the United States away from France and make the new country a valuable economic partner.[7] The western terms were that the United States would gain all of the area east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of Canada. The northern boundary would be almost the same as today.[8] The United States would gain fishing rights off Canadian coasts, and agreed to allow British merchants and Loyalists to try to recover their property. It was a highly favorable treaty for the United States, and deliberately so from the British point of view. Prime Minister Shelburne foresaw highly profitable two-way trade between Britain and the rapidly growing United States, as it indeed came to pass. Trade with France was always on a much smaller scale.[9][10][11]

The French Revolution and Napoleon

Six years later, the French Revolution toppled the Bourbon regime. At first, the United States was quite sympathetic to the new situation in France, where the hereditary monarchy was replaced by a constitutional republic. However, in the matter of a few years, the situation in France turned sour, as foreign powers tried to invade France and King Louis XVI was accused of high treason. The French revolutionary government then became increasingly authoritarian and brutal, which dissipated some of the United States' warmth for France.

A crisis emerged in 1793 when France found itself at war again with Great Britain and its allies, this time after the French revolutionary government had executed the king. The new federal government in the United States was uncertain how to respond. Should the United States recognize the radical government of France by accepting a diplomatic representative from it? Was the United States obliged by the alliance of 1778 to go to war on the side of France? The treaty had been called "military and economic", and as the United States had not finished paying off the French loan, would the military alliance be ignored as well? President George Washington (responding to advice from both Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson) recognized the French government, but did not support France in the war with Britain, as expressed in his 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality. The proclamation was issued and declared without Congressional approval. Congress instead acquiesced, and a year later passed a neutrality act forbidding U.S. citizens to participate in the war and prohibiting the use of U.S. soil as a base of operation for either side. Thus, the revolutionary government viewed Washington's policy as partial to the enemy.[12]

The first challenge to U.S. neutrality came from France, when its first diplomatic representative, the brash Edmond-Charles Genêt, toured the United States to organize U.S. expeditions against Spain and Britain. Exasperated, Washington demanded Genêt's recall, but by then the French Revolution had taken yet another turn and the new French ministers arrived to arrest Genêt. Washington refused to extradite Genêt (knowing he would otherwise be guillotined). Genêt became a U.S. citizen.[13]

France regarded Jay's Treaty (November 1794) between Britain and the United States as hostile. It opened a decade of trade when France was at war with Britain.

Timothy Pickering (1745-1829) was the third United States Secretary of State, serving in that office from 1795 to 1800 under Washington and John Adams. Biographer Gerald Clarfield says he was a "quick-tempered, self-righteous, frank, and aggressive Anglophile," who handled the French poorly. In response the French envoy Pierre Adet repeatedly provoked Pickering into embarrassing situations, then ridiculed his blunderings and blusterings to appeal to Republican Party opponents of the Administration.[14]

Quasi War 1798–1800

Signing of the Convention of 1800, ending the Quasi War and ending the Franco-American alliance.

To overcome this resentment John Adams sent a special mission to Paris in 1797 to meet the French foreign minister Talleyrand. The American delegation was shocked, however, when it was demanded that they pay monetary bribes in order to meet and secure a deal with the French government. Adams exposed the episode, known as the "XYZ Affair", which greatly offended Americans even though such bribery was not uncommon among the courts of Europe.[15]

Tensions with France escalated into an undeclared war—called the "Quasi-War." It involved two years of hostilities at sea, in which both navies attacked the other's shipping in the West Indies. The unexpected fighting ability of the U.S. Navy, which destroyed the French West Indian trade, together with the growing weaknesses and final overthrow of the ruling Directory in France, led Talleyrand to reopen negotiations. At the same time, President Adams feuded with Hamilton over control of the Adams' administration. Adams took sudden and unexpected action, rejecting the anti-French hawks in his own party and offering peace to France. In 1800 he sent William Vans Murray to France to negotiate peace; Federalists cried betrayal. The subsequent negotiations, embodied in the Convention of 1800 (also called the "Treaty of Mortefontaine") of September 30, 1800, affirmed the rights of Americans as neutrals upon the sea and abrogated the alliance with France of 1778. The treaty failed to provide compensation for the $20,000,000 "French Spoliation Claims" of the United States; the U.S. government eventually paid these claims. The Convention of 1800 ensured that the United States would remain neutral toward France in the wars of Napoleon and ended the "entangling" French alliance with the United States.[16] In truth, this alliance had only been viable between 1778 and 1783.[17][18]

Napoleon

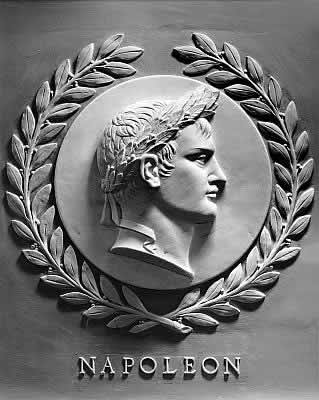

Bas-relief of Napoleon I in the chamber of the United States House of Representatives.

Spain was losing money heavily on the ownership of vast Louisiana territory, and was eager to turn it over to Napoleon in 1800. He envisioned it as the base (along with Haiti) of a New World empire. Louisiana would be a granary providing food to the enslaved labor force in the West Indies. President Jefferson could tolerate weak Spain but not powerful France in the west. He considered war to prevent French control of the Mississippi River. Jefferson sent his close friend, James Monroe, to France to buy as much of the land around New Orleans as he could. Surprisingly, Napoleon agreed to sell the entire territory. Because of an insuppressible slave rebellion in St. Domingue, modern-day Haiti, among other reasons, Bonaparte's North American plans collapsed. To keep Louisiana out of British hands in an approaching war he sold it in April 1803 to the United States for $15 million. British bankers financed the deal, taking American government bonds and shipping gold to Paris. The size of the United States was doubled without going to war.[19]

Britain and France resumed their war in 1803, just after the Purchase. Both challenged American neutrality and tried to disrupt trade with its enemy. The presupposition was that small neutral nations could benefit from the wars of the great powers. Jefferson distrusted both Napoleon and Great Britain, but saw Britain (with its monarchism, aristocracy and great navy and position in Canada) as the more immediate threat to American interests. Therefore, he and Madison took a generally pro-French position and used the embargo to hurt British trade. Both Britain and France infringed on U.S. maritime rights. The British infringed more and also impressed thousands of American sailors into the Royal Navy; France never did anything like impressment.[20] Jefferson signed the Embargo Act in 1807, which forbade all exports and imports. Designed to hurt the British, it hurt American commerce far more. The destructive Embargo Act, which had brought U.S. trade to a standstill, was rescinded in 1809, as Jefferson left office. Both Britain and France remained hostile to the United States. The War of 1812 was the logical extension of the embargo program as the United States declared war on Britain. However, there was never any sense of being an ally of France and no effort was made to coordinate military activity.[21]

France and Spain had not defined a boundary between Louisiana and neighboring territory retained by Spain, leaving this problem for the U.S. and Spain to sort out. The U.S. inherited the French claims to Texas, then in the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty traded these (and a little of the Mississippi drainage itself) in return for American possession of Florida, where American settlers and the U.S. Army were already encroaching, and acquisition of Spain's weak claims to the Pacific Northwest. Before three more decades had passed, the United States had annexed Texas.[22]

1815–1860

1835 cartoon by James Akin shows President Jackson challenging French King Louis Philippe, whose crown is falling off; Jackson is advised by king Neptune, and backed up by an American warship. On the left are French politicians, depicted as little frogs, complaining about the Americans.

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59), the most influential European student of American culture.

Relations between the two nations were generally quiet for two decades. The United States, in cooperation with Great Britain, issued the "Monroe Doctrine" in 1823 to keep European powers, especially Spain but also France, from seizing lands in the New World. The French had a strong interest in expanding commercial opportunity in Latin America, especially as the Spanish role was faltering. There was a desire among top French officials that some of the newly independent countries in Latin America might select a Bourbon king, but no actual operations ever took place. French officials ignored the American position. France and Austria, two reactionary monarchies, strenuously opposed American republicanism and wanted the United States to have no voice whatsoever in European affairs.[23]

A treaty between the United States and France in 1831 called for France to pay 25 million francs for the spoilation claims of American shipowners against French seizures during the Napoleonic wars. France did pay European claims, but refused to pay the United States. President Andrew Jackson was livid, In 1834 ordered the U.S. Navy to stand by and asked Congress for legislation. Jackson's political opponents blocked any legislation. France was annoyed but finally voted the money if the United States apologized. Jackson refused to apologize, and diplomatic relations were broken off until in December 1835 Jackson did offer some friendlier words. The British mediated, France paid the money, and cordial relations were resumed.[24]

Modest cultural exchanges resumed, most famously and intense study visits by Gustave de Beaumont and Alexis de Tocqueville, the author of Democracy in America (1835). The book was immediately a popular success in both countries, and to this day helps shape American self-understanding. American writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson appealed to an appreciative French audience. French utopian socialists Projected an idealized American society as a model for the future. French travelers to the United States were often welcomed in the name of the Lafayette, who made a triumphant American tour in 1824. Numerous political exiles found refuge in New York.[25]

In the 1840s Britain and France considered sponsoring continued independence of the Republic of Texas and blocking U.S. moves to obtain California. Balance of power considerations made Britain want to keep the western territories out of U.S. hands to limit U.S. power; in the end, France opposed such intervention in order to limit British power, the same reason for which France had sold Louisiana to the U.S. and earlier supported the American Revolution.[26] Thus the great majority of the territorial growth of the continental United States was accomplished with French support.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, 1861–65, France was neutral. However Napoleon III favored the Confederacy, hoping to weaken the United States, create a new ally in the Confederacy, safeguard the cotton trade and protect his large investment in controlling Mexico. France was too weak to declare war alone (which might cause Prussia to attack), and needed British support. The British were unwilling to go to war and nothing happened.[27]

Napoleon III took advantage of the war in 1863, when he installed Austrian archduke Maximilian of Habsburg on the throne in Mexico. Washington protested and refused to recognize the new government.[28] Napoleon hoped that a Confederate victory would result in two weak nations on Mexico's northern borders, allowing French dominance in a country ruled by its puppet Emperor Maximilian. Matías Romero, Júarez's ambassador to the United States, gained some support in Congress for possibly intervening on Mexico's behalf against France's occupation.[29][30] However, Secretary of State William Seward was cautious in limiting US aid to Mexico. He did not want a war with France before the Confederacy was defeated.[31]

U.S. celebration of the anniversary of the Mexican victory over the French on Cinco de Mayo, 1862 started the following year and has continued up to the present. In 1865, the United States used increasing diplomatic pressure to persuade Napoleon III to end French support of Maximilian and to withdraw French troops from Mexico. When the French troops left the Mexicans executed the puppet emperor Maximilian.[32]

After a decade of extreme instability, the North American scene stabilized by 1867. The victory of the Union, French withdrawal from Mexico, British disengagement from Canada and the Russian sale of Alaska left the United States dominant, yet with Canadian and Mexican independence intact.[33]

1866–1906

Construction of the Statue of Liberty in Paris.

The removal of Napoleon III in 1870 after the Franco-Prussian War helped improve Franco–American relations. During the Siege of Paris, the small American population, led by the U.S. Minister to France Elihu B. Washburne, provided much medical, humanitarian, and diplomatic support to peoples, gaining much credit to the Americans.[34] In subsequent years the balance of power in the relationship shifted as the United States, with its very rapid growth in wealth, industry and population, came to overshadow the old powers. Trade was at a low level, and mutual investments were uncommon.

All during this period the relationship remained friendly—as symbolized by the Statue of Liberty, presented in 1884 as a gift to the United States from the French people. From 1870 until 1918, France was the only major republic in Europe, which endeared it to the United States. Many French people held the United States in high esteem, as a land of opportunity and as a source of modern ideas. Few French people emigrated to the United States. Intellectuals, however, saw the United States as a land built on crass materialism, lacking in a significant culture, and boasting of its distrust of intellectuals. Very few self-styled French intellectuals were admirers.[35]

In 1906, when Germany challenged French influence in Morocco (see Tangier Crisis and Agadir Crisis), President Theodore Roosevelt sided with the French. However, as the Americans grew mightily in economic power, and forged closer ties with Britain, the French increasingly talked about an Anglo-Saxon threat to their culture.[36]

Student exchange became an important factor, especially Americans going to France to study. The French were annoyed that so many Americans were going to Germany for post-graduate education, and discussed how to attract more Americans. After 1870, hundreds of American women traveled to France and Switzerland to obtain their medical degrees. The best American schools were closed to them and chose an expensive option superior to what they were allowed in the U.S.[37] In the First World War, normal enrollments plunged at French universities, and the government made a deliberate decision to attract American students partially to fill the enrollment gap, and more importantly to neutralize German influences in American higher education. Thousands of American soldiers, waiting for their slow return to America after the war ended in late 1918, enrolled in university programs set up especially for them.[38]

World War I (1914–19)

The Great War (1917–18)

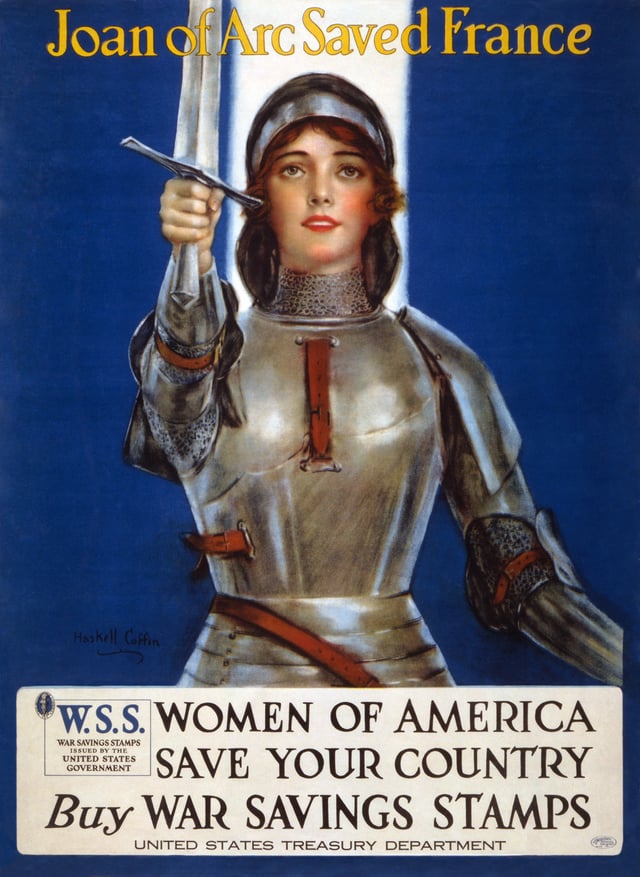

United States patriotic poster depicting the French heroine Joan of Arc during the World War I.

During World War I the United States was initially neutral but eventually entered the conflict in 1917 and provided much-needed money—as loans to be repaid—that purchased American food, oil and chemicals for the French effort. The American troops were sent over without their heavy equipment (so that the ships could carry more soldiers). They used French artillery, airplanes and tanks, such as the SPAD XIII fighter biplane and Renault FT light tank serving in the aviation and armored formations of the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front in 1918. In 1918 the United States sent over a million combat troops who were stationed to the south of the main French lines. They gave the Allies a decisive edge, as the Germans were unable to replace their heavy losses and lost their self-confidence by September 1918.[39]

The peace settlement (1919)

Wilson had become the hero of the war for Frenchmen, and his arrival in Paris was widely hailed. However, the two countries clashed over France's policy to weaken Germany and make it pay for the entire French war. The burning ambition of French Premier Georges Clemenceau was to ensure the security of France in the future; his formula was not friendship with Germany restitution, reparations, and guarantees. Clemenceau had little confidence in what he considered to be the unrealistic and utopian principles of US President Woodrow Wilson: "Even God was satisfied with Ten Commandments, but Wilson insists on fourteen" (a reference to Wilson's "Fourteen Points"). The two nations disagreed on debts, reparations, and restraints on Germany.

Clemenceau was also determined that a buffer state consisting of the German territory west of the Rhine River should be established under the aegis of France. In the eyes of the U.S. and British representatives, such a crass violation of the principle of self-determination would only breed future wars, and a compromise was therefore offered Clemenceau, which he accepted. The territory in question was to be occupied by Allied troops for a period of five to fifteen years, and a zone extending fifty kilometers east of the Rhine was to be demilitarized. Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George agreed that the United States and Great Britain, by treaty, would guarantee France against German aggression. Republican leaders in Washington were willing to support a security treaty with France. It failed because Wilson insisted on linking it to the Versailles Treaty, which the Republicans would not accept without certain amendments Wilson refused to allow.[40]

While French historian Duruoselle portrays Clemenceau as wiser than Wilson, and equally compassionate and committed to justice but one who understood that world peace and order depended on the permanent suppression of the German threat.[41] Blumenthal (1986), by contrast, says Wilson's policies were far sounder than the harsh terms demanded by Clemenceau. Blumenthal agrees with Wilson that peace and prosperity required Germany's full integration into the world economic and political community as an equal partner. One result was that in the 1920s the French deeply distrusted the Americans, who were loaning money to Germany (which Germany used to pay its reparations to France and other Allies), while demanding that France repay its war loans from Washington.[42][43][44]

Interwar years (1919–38)

The French ambassador's residence in Washington, D.C. It served as the French embassy from 1936 to 1985.

During the interwar years, the two nations remained friendly. Beginning in the 1920s, U.S. intellectuals, painters, writers, and tourists were drawn to French art, literature, philosophy, theatre, cinema, fashion, wines, and cuisine.

A number of American artists, such as Josephine Baker, experienced popular success in France. Paris was also quite welcoming to American jazz music and black artists in particular, as France, unlike a significant part of the United States at the time, had no racial discrimination laws. Numerous writers such as William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and others were deeply influenced by their experiences of French life. Known as the Lost Generation, their time in Paris was documented by Hemingway in his memoir A Moveable Feast.

However, anti-Americanism came of age in the 1920s, as many French traditionalists were alarmed at the power of Hollywood and warned that America represented modernity, which in turn threatened traditional French values, customs, and popular literature.[45] The alarm of American influence escalated half a century later when Americans opened a $4 billion Disneyland Paris theme park in 1992. It attracted larger crowds than the Louvre, and soon it was said that the iconic American cartoon character Mickey Mouse had become more familiar than Asterix among French youth.[46][47]

The J. Walter Thompson Company of New York was the leading American advertising agency of the interwar years. It established branch offices in Europe, including one in Paris in 1927. Most of these branches were soon the leading local agencies, as in Britain and Germany, JWT-Paris did poorly from the late 1920s through the early 1960s. The causes included cultural clashes between the French and Americans and subtle anti-Americanism among potential clients. Furthermore, The French market was heavily regulated and protected to repel all foreign interests, and the American admen in Paris were not good at hiding their condescension and insensitivity.[48]

In 1928 the two nations were the chief sponsors of the Kellogg–Briand Pact which outlawed war. The pact, which was endorsed by most major nations, renounced the use of war, promoted peaceful settlement of disputes, and called for collective force to prevent aggression. Its provisions were incorporated into the United Nations Charter and other treaties and it became a stepping stone to a more activist American policy.[49] Diplomatic intercourse was minimal under Franklin D. Roosevelt from 1933 to 1939.[50]

World War II (1938–45)

American Cemetery and Memorial in Suresnes, France.

In the approach to Second World War the United States helped France arm its air force against the Nazi threat. The successful performance of German warplanes during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) suddenly forced France to realize its military inferiority. Germany had better warplanes, more of them, pilots with wartime experience in Spain, and much more efficient factories. President Roosevelt had long been interested in France, and was a personal friend of French Senator, Baron Amaury de La Grange. In late 1937 he told Roosevelt about the French weaknesses, and asked for military help. Roosevelt was forthcoming, and forced the War Department to secretly sell the most modern American airplanes to France.[51][52] Paris frantically expanded its own aircraft production, but it was too little and too late. France and Britain declared war on Germany when it invaded Poland in September 1939, but there was little action until the following spring. Suddenly a German blitzkrieg overwhelmed Denmark and Norway and trapped French and British forces in Belgium. France was forced to accept German terms and a pro-fascist dictatorship took over in Vichy France.[53]

Vichy France (1940–44)

Langer (1947) argues that Washington was shocked by the sudden collapse of France in spring 1940, and feared that Germany might gain control of the large French fleet, and exploit France's overseas colonies. This led the Roosevelt administration to maintain diplomatic relations. FDR appointed his close associate Admiral William D. Leahy as ambassador. Vichy regime was officially neutral but it was helping Germany. The United States severed diplomatic relations in late 1942 when Germany took direct control of areas that Vichy had ruled, and Vichy France became a Nazi puppet state.[54] More recently, Hurstfield (1986) concluded that Roosevelt, not the State Department, had made the decision, thereby deflecting criticism from leftwing elements of his coalition onto the hapless State Department. When the experiment ended FDR brought Leahy back to Washington as his top military advisor and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.[55]

Free French Forces

Relations were strained between Roosevelt and Charles De Gaulle, the leader of the Free French. After Normandy the Americans and the Allies knew it was only a matter of time before the Nazis lost. Eisenhower did give De Gaulle his word that Paris would be liberated by the French as the Americans had no interest in Paris, a city they considered lacking tactical value. It was therefore easy for Eisenhower to let De Gaulle's FFI take the charge. There was one important aspect of Paris that did seem to matter to everyone: it was its historical and cultural significance. Hitler had given the order to bomb and burn Paris to the ground; he wanted to make it a second Stalingrad. The Americans and the Allies could not let this happen.[56] The French 2nd armored division with Maj. Gen Phillipe Leclerc at its helm was granted this supreme task of liberating Paris.[57] General Leclerc was ecstatic at this thought because he wanted to wipe away the humiliation of the Vichy Government.[56][58]

General George S. Patton was at the command of the U.S. Third Army that swept across northern France. It campaigned in Lorraine for some time, but it was one of the least successful of Patton's career. While in Lorraine, he annexed the Maj. Gen. Phillipe Leclerc's battalion into his army.[56] Leclerc did not respect his American counterparts because like the British he thought that they were new to the war. Therefore, he thought the Americans did not know what they were doing on the field. After being more trouble than help Patton let Leclerc go for Paris. The French then went on to liberate Paris from the east while the 4th U.S. Infantry (they were originally part of Patton's Army) came from the west. Because of Eisenhower's deal with De Gaulle, the Liberation was left to the French's 2nd armored division.[56][57][59] With De Gaulle becoming the head of state, the Americans and the British had no other choice, but to accept him. Eisenhower even came to Paris to give De Gaulle his blessing.[60]

Roosevelt opposes French colonies in Asia

Roosevelt was strongly committed to terminating European colonialism in Asia. especially French Indochina. He wanted to put it under an international trusteeship. He wanted the United States to work closely with China to become the policeman for the region and stabilize it; the U.S. would provide suitable financing. The scheme was directly contrary to the Free French, for de Gaulle had a grand vision of the French overseas empire as the base for his returned to defeat Vichy France. Roosevelt could not abide de Gaulle, but Winston Churchill realized that Britain needed French help to reestablish its position in Europe after the war. He and the British foreign office decided to work closely with de Gaulle to achieve that goal, and therefore they had to frustrated Roosevelt's decolonization scheme. In doing so, they had considerable support from like-minded American officials. The basic weakness of Roosevelt's scheme was its dependence on Chiang Kai-shek the ruler of China. Chiang's regime virtually collapsed under Japanese pressures in 1944, and Japan overran the American airbases that were built to attack Japan. The Pentagon's plans to use China as a base to destroy Japan collapsed, so the U.S. Air Force turned its attention to attacking Japan with very long-range B-29 bombers based in the Pacific. The American military no longer needed China or Southeast Asia. China clearly was too weak to be a policeman. With the defeat of Japan, Britain took over Southeast Asia and returned Indochina to France. Roosevelt realized his trusteeship plan was dead, and accepted the British-French actions as necessary to stabilize Southeast Asia.[61]

Postwar years

In the postwar years, both cooperation and discord persisted. After de Gaulle left office in January 1946, the logjam was broken in terms of financial aid. Lend Lease had barely restarted when it was unexpectedly ended in August 1945. The U.S. Army shipped in food, 1944-46. U.S. Treasury loans and cash grants were given in 1945-47, and especially the Marshall Plan gave large sums (1948–51). There was post-Marshall aid (1951–55) designed to help France rearm and provide massive support for its war in Indochina. Apart from low-interest loans, the other funds were grants that did not involve repayment. The debts left over from World War I, whose payment had been suspended since 1931, was renegotiated in the Blum-Byrnes agreement of 1946. The United States forgave all $2.8 billion in debt from the First World War, and gave France a new loan of $650 million. In return French negotiator Jean Monnet set out the French five-year plan for recovery and development.[62] The Marshall Plan gave France $2.3 billion with no repayment. The total of all American grants and credits to France from 1946 to 1953, amounted to $4.9 billion.[63] A central feature of the Marshall Plan was to encourage international trade, reduce tariffs, lower barriers, and modernize French management. The Marshall Plan set up intensive tours of American industry. France sent 500 missions with 4700 businessmen and experts to tour American factories, farms, stores and offices. They were especially impressed with the prosperity of American workers, and how they could purchase an inexpensive new automobile for nine months work, compared to 30 months in France.[64] Some French businesses resisted Americanization, but the most profitable, especially chemicals, oil, electronics, and instrumentation, seized upon the opportunity to attract American investments and build a larger market.[65] The U.S. insisted on opportunities for Hollywood films, and the French film industry responded with new life.[66]

Cold War

Charles de Gaulle, Heinrich Lübke and Lyndon B. Johnson, 1967

In 1949 the two became formal allies through the North Atlantic treaty, which set up the NATO military alliance. Although the United States openly disapproved of French efforts to regain control of colonies in Africa and Southeast Asia, it supported the French government in fighting the Communist uprising in French Indochina.[67] However, in 1954, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower declined French requests for aerial strikes to relieve besieged French forces at Dien Bien Phu.[68][69]

Both countries opposed the Soviet Union in Cold War confrontations but went through another crisis in 1956. When France, Britain, and Israel attacked Egypt, which had recently nationalized the Suez Canal and shown signs of warming relations with the Soviet Union and China, Eisenhower forced them to withdraw. By exposing their diminished international stature, the Suez Crisis had a profound impact on the UK and France: the UK subsequently aligned its Middle East policy to that of the United States,[70] whereas France distanced itself from what it considered to be unreliable allies and sought its own path.[71]

While occasional tensions surfaced between the governments, the French public, except for the Communists, generally had a good opinion of the United States throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s. Despite some cultural friction, the United States was seen as a benevolent giant, the land of modernity, and French youth took a taste to American culture such as chewing gum, Coca-Cola, and rock and roll.

De Gaulle

In the 1950s France sought American help in developing nuclear weapons; Eisenhower rejected the overtures for four reasons. Before 1958, he was troubled by the political instability of the French Fourth Republic and worried that it might use nuclear weapons in its colonial wars in Vietnam and Algeria. Charles de Gaulle brought stability to the Fifth Republic starting in 1958, but Eisenhower was still hesitant to assist in the nuclearization of France. De Gaulle wanted to challenge the Anglo-Saxon monopoly on Western weapons by having his own Force de frappe. Eisenhower feared his grandiose plans to use the bombs to restore French grandeur would weaken NATO. Furthermore, Eisenhower wanted to discourage the proliferation of nuclear arms anywhere.[72]

Charles de Gaulle also quarreled with Washington over the admission of Britain into the European Economic Community. These and other tensions led to de Gaulle's decision in 1966 to withdraw French forces from the integrated military structure of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and forced it to move its headquarters to Belgium. De Gaulle's foreign policy was centered on an attempt to limit the power and influence of both superpowers, which would increase France's international prestige in relative terms. De Gaulle hoped to move France from being a follower of the United States to a leading first-world power with a large following among certain non-aligned Third World countries. The nations de Gaulle considered potential participants in this grouping were those in France's traditional spheres of influence, Africa and the Middle East.[73]

The two nations differed over the waging of the Vietnam War, in part because French leaders were convinced that the United States could not win. The recent French experience with the Algerian War of Independence was that it was impossible, in the long run, for a democracy to impose by force a government over a foreign population without considerable manpower and probably the use of unacceptable methods such as torture. The French popular view of the United States worsened at the same period, as it came to be seen as an imperialist power.[74][75]

1970–1989

François Mitterrand and Ronald Reagan, 1981

Relations improved somewhat after de Gaulle lost power in 1969. Small tensions reappeared intermittently. France, more strongly than any other nation, has seen the European Union as a method of counterbalancing American power, and thus works towards such ends as having the Euro challenge the preeminent position of the United States dollar in global trade and developing a European defense initiative as an alternative to NATO. Overall, the United States had much closer relations with the other large European powers, Great Britain, Germany and Italy. In the 1980s the two nations cooperated on some international matters but disagreed sharply on others, such as Operation El Dorado Canyon and the desirability of a reunified Germany. The Reagan administration did its best efforts to prevent France and other European countries from buying natural gas from Russia, through the construction of the Siberia-Europe pipeline. The European governments, including the French, were undeterred and the pipeline was finally built.[76]

Anti-Americanism

Richard Kuisel, an American scholar, has explored how France partly embraced American consumerism while rejecting much of American values and power. He writes in 2013:

America functioned as the "other" in configuring French identity. To be French was not to be American. Americans were conformists, materialists, racists, violent, and vulgar. The French were individualists, idealists, tolerant, and civilized. Americans adored wealth; the French worshiped la douceur de vivre. This caricature of America, which was already broadly endorsed at the beginning of the century, served to essentialize French national identity. At the end of the twentieth century, the French strategy [was to use] America as a foil, as a way of defining themselves as well as everything from their social policies to their notion of what constituted culture.[77]

On the other hand, Kuisel identifies several strong pull effects:

American products often carried a representational or symbolic quality. They encoded messages like modernity, youthfulness, rebellion, transgression, status, and freedom ... There was the linkage with political and economic power: historically culture has followed power. Thus Europeans learned English because it is a necessary skill in a globalized environment featuring American technology, education, and business. Similarly the size and power of U.S. multinationals, like that of the global giant Coca-Cola, helped American products win market shares. Finally, it must be acknowledged, that there has been something inherently appealing about what we make and sell. Europeans liked Broadway musicals, TV shows, and fashions. We know how to make and market what others want.[78]

Middle East conflict

France under President François Mitterrand supported the 1991 Persian Gulf War in Iraq as a major participant under Operation Daguet. The French Assemblee Nationale even took the "unprecedented decision" to place all French forces in the Gulf under United States command for the duration of the war.[79]

9-11

All the political elements in France strongly denounced the barbaric acts of the Al-Qaeda Terrorists in the 9/11 attack in 2001. President Jacques Chirac —later known for his frosty relationship with President George W. Bush—ordered the French secret services to collaborate closely with U.S. intelligence, and created Alliance Base in Paris, a joint-intelligence service center charged with enacting the Bush administration's War on Terror. However all the political elements rejected the idea of a full-scale war against Islamic radical terrorism. Memories of the Algerian war, and its disastrous impact on French internal affairs, as well as more distant memories of its own failed Vietnam war, played a major role. Furthermore, France had to deal with a large Islamic population of its own, which Chirac could not afford to alienate. As a consequence, France refused to support militant American efforts in the Middle East. Numerous works by novelists and film makers criticized the American efforts to transform the disaster into a justification for war.[80][81]

Iraq War

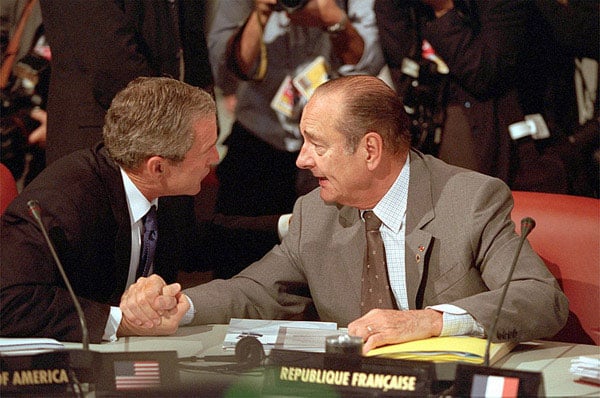

George W. Bush and Jacques Chirac during the 27th G8 summit, 2001

In March 2003 France, along with Germany, China, and Russia, opposed the proposed UN resolution that would have authorized a U.S. invasion of Iraq.[82] During the run-up to the war, French foreign minister Dominique de Villepin emerged as a prominent critic of the American Iraq policies. Despite the recurring rifts, the often ambivalent relationship remained formally intact. The United States did not need French help, and instead worked closely with Britain and its other allies.[83]

Angry American talk about boycotting French products in retaliation fizzled out, having little impact beyond the short-lived renaming of French fries as "Freedom fries."[84] Nonetheless, the Iraq war, the attempted boycott, and anti-French sentiments caused a hostile negative counter reaction in Europe.[85] By 2006, only one American in six considered France an ally of the United States.[86]

The ire of American popular opinion towards France during the run-up to the 2003 Iraq Invasion was primarily due to the fact that France decided not to intervene in Iraq (because the French did not believe the reasons given to go to war, such as the supposed link between Saddam Hussein and Al-Qaeda, and the purported weapons of mass destruction to be legitimate). This contributed to the perception of the French as uncooperative and unsympathetic in American popular opinion at the time. This perception was quite strong and persisted despite the fact that France was and had been for some time a major ally in the campaign in Afghanistan (see for example the French forces in Afghanistan) where both nations (among others in the US-led coalition) were dedicated to the removal of the rogue Taliban, and the subsequent stabilization of Afghanistan, a recognized training ground and safe haven for terrorists intent on carrying out attacks in the Western world.

As the Iraq War progressed, relations between the two nations began to improve. In June 2006 the Pew Global Attitudes Project revealed that 52% of Americans had a positive view of France, up from 46% in 2005.[87] Other reports indicate Americans are moving not so much toward favorable views of France as toward ambivalence,[88] and that views toward France have stabilized roughly on par with views toward Russia and China.[89]

Following issues like Hezbollah's rise in Lebanon, Iran's nuclear program and the stalled Israeli-Palestinian peace process, George Bush urged Jacques Chirac and other world leaders to "stand up for peace" in the face of extremism during a meeting in New York on September 19, 2006.

Strong French and American diplomatic cooperation at the United Nations played an important role in the Cedar Revolution, which saw the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon. France and the United States also worked together (with some tensions) in crafting UN resolution 1701, intended to bring about a ceasefire in the 2006 Israeli–Lebanese conflict.

Sarkozy administration

U.S. President Barack Obama and French President Nicolas Sarkozy in the White House in 2010.

In 2007, Sarkozy delivered a speech before the U.S. Congress that was seen as a strong affirmation of French–American ties; during the visit, he also met with President George W. Bush as well as senators John McCain and Barack Obama (before they were chosen as presidential candidates).[95]

Obama and McCain also met with Sarkozy in Paris after securing their respective nominations in 2008. After receiving Obama in July, Sarkozy was quoted saying "Obama? C'est mon copain",[96] which means "Obama? He's my buddy." Because of their previous acquaintance, relations between the Sarkozy and Obama administrations were expected to be warm.[97]

In 2011 the two countries were part of the multi-state coalition which launched a military intervention in Libya where they led the alliance and conducted 35% of all NATO strikes.

Hollande and Obama

U.S. President Barack Obama and French President François Hollande in February 2014.

After president François Hollande pledged support for military action against Syria, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry referred to France as "our oldest ally".[101]

During his state visit Hollande toured Monticello where he stated:

On September 19, 2014 it was announced that France had joined the United States in bombing Islamic State targets in Iraq as a part of the 2014 American intervention in Iraq. United States president, Barack Obama & the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Martin Dempsey, praised Hollande's decision to join the operation:

As one of our oldest and closest allies, France is a strong partner in our efforts against terrorism and we are pleased that French and American service members will once again work together on behalf of our shared security and our shared values.[108]

Said Obama,

the French were our very first ally and they're with us again now.

Stated Dempsey, who was visiting the Normandy landing beaches and the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial with his French counterpart, General Pierre de Villiers.[109]

On April 18, 2015, the Hermione (a replica of the famous 1779 French frigate Hermione) departed La Rochelle, France, bound for Yorktown, Virginia, USA, where it arrived in early June. After that it has visited ports along the eastern seaboard en route to New York City for Independence Day celebrations. The original Concorde class frigate became famous when she ferried General Lafayette to the United States in 1780 to allow him to rejoin the American side in the American Revolutionary War. French President François Hollande was at La Rochelle to see the replica off, where he stated:[110]

L'Hermione is a luminous episode of our history. She is a champion of universal values, freedom, courage and of the friendship between France and the United States,[111]

President Barack Obama in a letter commemorating the voyage stated:

For more than two centuries, the United States and France have stood united in the freedom we owe to one another. From the battlefields where a revolution was won to the beaches where the liberation of a continent began, generations of our peoples have defended the ideals that guide us-overcoming the darkness of oppression and injustice with the light of liberty and equality, time and again. As we pay tribute to the extraordinary efforts made by General Lafayette and the French people to advance the Revolutionary cause, we reflect on the partnership that has made France our Nation's oldest ally. By continuing to renew and deepen our alliance in our time, we ensure generations to come can carry it forward proudly.[112]

The ship was given a copy of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen by the French President to be presented to the American President upon its arrival.[113]

Macron and Trump

U.S. President Donald Trump and French President Emmanuel Macron in Washington, April 2018.

Shortly after Donald Trump’s election in November 2016, 75 percent of French adults held a negative opinion of him. Most said he would damage U.S.-European relations and threaten world peace. On the French right, half of the supporters of Marine Le Pen, opposed Trump, despite sharing many of his views on immigration, and trade.[114]

On July 12, 2017, President Donald Trump visited France as the guest of President Emmanuel Macron. The two leaders discussed issues that included counter-terrorism and the war in Syria, but played down topics where they sharply disagreed, especially trade, immigration and climate change.[115]

In late 2018, President Trump attacked President Macron over nationalism, tariffs, France's World War Two defeat, plans for a European army and the French leader's approval ratings. This followed Mr Trump's Armistice Day visit to Paris which was heavily criticized in both France and the United States. Mr Trump had been expected to attend a ceremony at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery where American and French troops repelled German forces in 1918, but called off the visit because of rain.

A French government spokesman criticized Mr Trump for displaying a lack of common decency as France was marking the anniversary of the Bataclan terrorist attack.[116]

Also in December French President Macron criticized President Trump over his decision to withdraw US troops from Syria, stating: "To be allies is to fight shoulder to shoulder. It’s the most important thing for a head of state and head of the military," and "An Ally Should Be Dependable," Macron went on to praise US Defense Secretary General Jim Mattis, calling him a "reliable partner". Mattis resigned over Trump’s announcement.[119][120]

In April 2019, the departing French ambassador to the United States Gérard Araud commented on the Trump administration and the US:[121]

Basically, this president and this administration don't have allies, don't have friends. It's really [about] bilateral relationships on the basis of the balance of power and the defense of narrow American interest.[122]

And:

...we don't have interlocutors... ...[When] we have people to talk to, they are acting, so they don't have real authority or access. Basically, the consequence is that there is only one center of power: the White House.[122]

On France working with the US:

...We really don't want to enter into a childish confrontation and are trying to work with our most important ally, the most important country in the world.[123]

In July US President Donald Trump threatened tariffs against France in retaliation for France enacting a digital services tax against multinational firms. With Trump tweeting:[124]

France just put a digital tax on our great American technology companies. If anybody taxes them, it should be their home Country, the USA. We will announce a substantial reciprocal action on Macron's foolishness shortly. I've always said American wine is better than French wine![124]

French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire indicated France would follow through with its digital tax plans.[124] French Agriculture Minister Didier Guillaume responded on French TV:

It's absurd, in terms of having a political and economic debate, to say that if you tax the 'GAFAs', I'll tax wine. It's completely moronic.[125]

After President Trump again indicated his intentions to impose taxes on French wine over France's digital tax plans, President of the European Council Donald Tusk stated the European Union would support France and impose retaliatory tariffs on the US.[126]

See also

Francophile

Francophobia

French American

Freedom fries