Ferrocarril Transístmico

Ferrocarril Transístmico

| Locale | Isthmus of Tehuantepec |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | FCCM |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm(4 ft 81⁄2 in) |

| Website | www.ferroistmo.com.mx [18] |

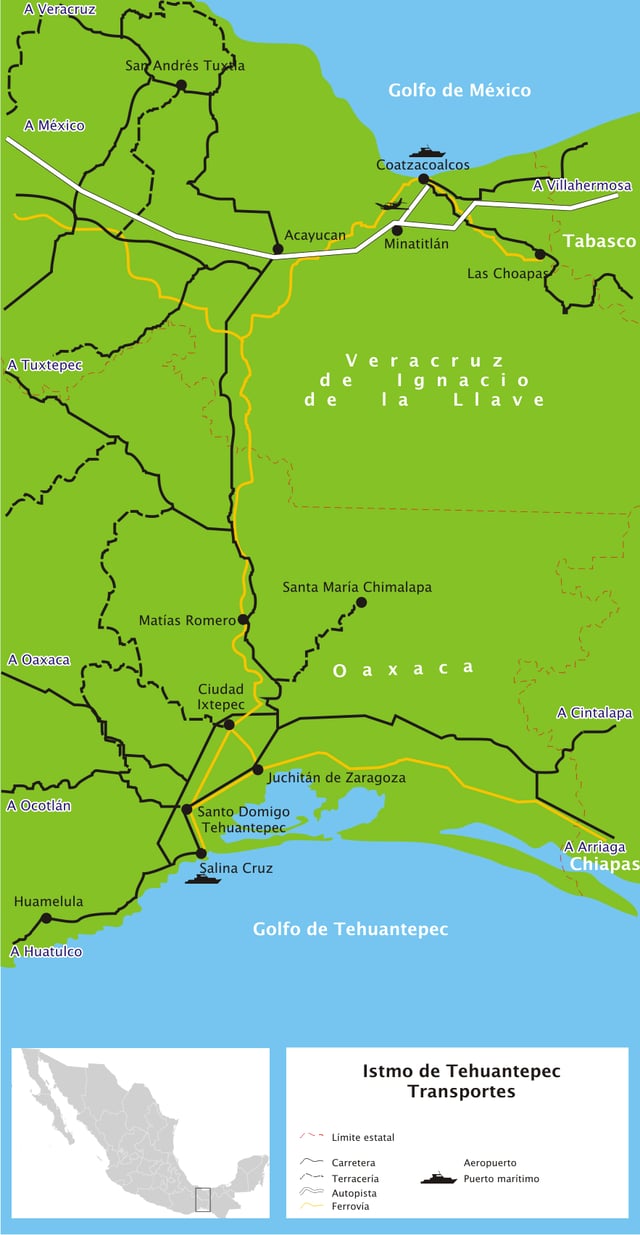

The Ferrocarril Transístmico (Spanish: Trans-Isthmic Railroad), also known as Ferrocarril del Istmo de Tehuantepec, S.A. de C.V. or simply Ferroistmo,[1] is today a railroad with no rolling stock, owned by the Mexican government, that crosses the Isthmus of Tehuantepec between Puerto Mexico, Veracruz, and Salina Cruz, Oaxaca. It is leased to Ferrocarril del Sureste FERROSUR. It was formerly leased to Ferrocarriles Chiapas-Mayab until Genesee & Wyoming gave up its concession in 2007.[2] Originally it was known as the Tehuantepec Railway.

| Locale | Isthmus of Tehuantepec |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | FCCM |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm(4 ft 81⁄2 in) |

| Website | www.ferroistmo.com.mx [18] |

History of the Tehuantepec Railway

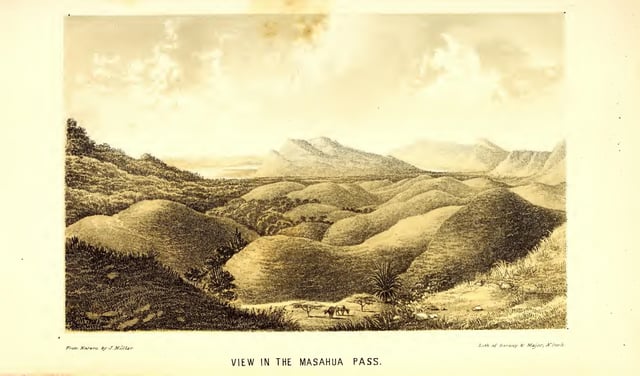

An illustration from Barnard's Survey of the Tehuantepec route

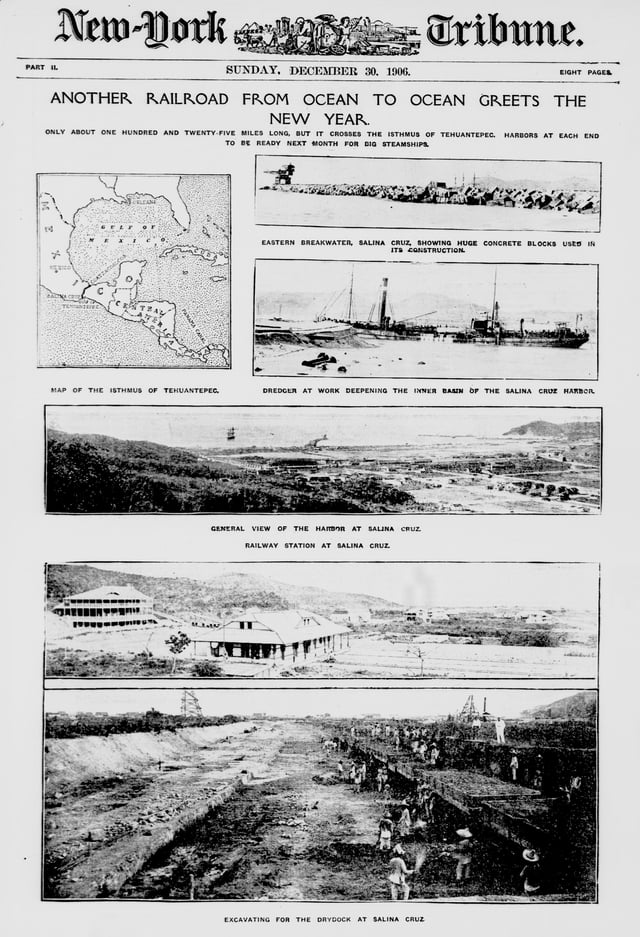

Newspaper report of the completion of the Tehuantepac Railroad

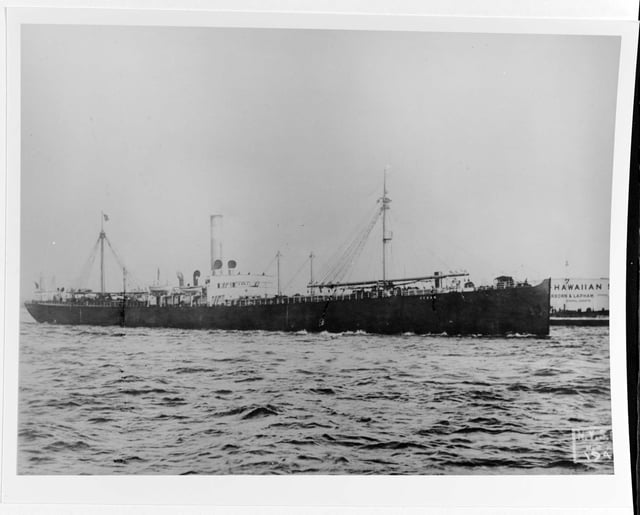

SS Texan , one of the freighters used on the Tehuantepec route[14]

The potential of the route from the Atlantic to the Pacific across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec has long been appreciated. As early as 1814 the Spanish government authorized a canal across the Isthmus. Soon after Mexico became independent in 1821, surveys were carried out which recommended constructing a plank trail for wagons through the Chivela Pass, with the northernmost part of the route using the Coatzacoalcos River which flows northward to the Gulf of Mexico on the Atlantic side of the isthmus. The river would be dredged to allow navigation. Nothing came of either of these plans[3][4][5].

More serious planning began in the early 1840s, when José de Garay, the First Officer of the Ministry of War obtained a concession on the route and carried out a more thorough survey[3]. After many failed attempts to obtain funding, the concession was taken over by a New Orleans company, The Tehuantepec Railroad Company of New Orleans (TRCNO). Despite diplomatic problems over the status of the concession, a further survey of the route was carried out by Major John G. Barnard. This was published in 1852[6].

The years between 1852 and 1861 were turbulent both diplomatically and financially. The opening of the Panama Railroad in 1854 provided competition for the Tehuantepec route, but also gave warning that the TRNCO's cost estimates were wildly optimistic. The Panic of 1857 made raising capital for transportation projects more difficult. There were disputes over the concession with the Mexican Government[7]. In spite of this, the company managed to construct a wagon trail (not a railroad) along the route, and offer a service for passengers and mail from New Orleans to San Francisco, starting in 1858. It was too little too late, however, and the company became insolvent in 1860. The outbreak of the American Civil War and the French intervention in Mexico the following year ended any immediate hope of reviving the project[5].

After the Civil War ended, there was once again interest in trans-isthmus routes, in particular for a canal. A commission was appointed by the US Government in 1872. A new survey of the Tehuantepec route had been carried out by Admiral R. W. Shufeldt in 1870, but in spite of his positive report[8] the commission recommended a route through Nicaragua in 1876[9]. No government action resulted, however, and actual canal construction was started in Panama in 1881 by a French company headed by Ferdinand de Lesseps.

A radically different solution was proposed by James B. Eads - a ship-railway. Rather than a canal, he proposed a 6-track railway across the isthmus, with ships of up to 6,000 tons carried in a specially designed cradle[10]. Eads' ideas received considerable support in the USA, but he died in 1887, and this was effectively the end of the proposal[9].

Railroad construction actually continued during this period, and the line was completed in 1894. However it had many problems, including inadequate port facilities at each end, and varying standards of construction along the route. It soon became clear that a complete overhaul was necessary, and Weetman D. Pearson was contracted by the Mexican Government to undertake the work. The line was stabilized, and where necessary structures were rebuilt. Port facilities were established at Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz. The newly refurbished line opened in 1907[11][12][9]. The locomotives on the line were oil-burning steam locomotives. The Tehuantepec Railroad was one of the first to use this source of power[13].

The American-Hawaiian Steamship Company, which had been operating from San Francisco and Hawaii to New York through the Straits of Magellan contracted to provide connecting steamship lines to both ends of the railroad, allowing a 25 day service between San Francisco and New York[15]. Sugar became a major part of the freight, amounting to 250,000 tons annually[16], and most of the sugar from Hawaii to Philadelphia and New York was carried on this route[17].

The railroad prospered for seven years, until the Panama Canal opened in 1914. Despite optimistic forecasts that there was plenty of business for both the railroad and the canal[4], business declined drastically after 1914, not helped by the Mexican Revolution and the onset of the First World War. The railroad continued to handle substantial passenger traffic well into the fifties, but ceased to be a significant carrier of freight[12][9].

Transport Routes in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

Map from Wikicommons

See also

American-Hawaiian Steamship Company

Ferrocarril de Veracruz al Istmo

List of Mexican railroads