Federal Aviation Administration

Federal Aviation Administration

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 23, 1958 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | Orville Wright Federal Building800 Independence Avenue SWWashington, D.C., U.S.20591 |

| Annual budget | US$15.956 billion (FY |

| Agency executive | |

| Parent agency | U.S.Department of Transportation |

| Website | |

| Footnotes | |

| [1][2] | |

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is a governmental body of the United States with powers to regulate all aspects of civil aviation in that nation as well as over its surrounding international waters. Its powers include the construction and operation of airports, air traffic management, the certification of personnel and aircraft, and the protection of U.S. assets during the launch or re-entry of commercial space vehicles. Powers over neighboring international waters were delegated to the FAA by authority of the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Created in August 1958, the FAA replaced the former Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and later became an agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation.

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 23, 1958 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | Orville Wright Federal Building800 Independence Avenue SWWashington, D.C., U.S.20591 |

| Annual budget | US$15.956 billion (FY |

| Agency executive | |

| Parent agency | U.S.Department of Transportation |

| Website | |

| Footnotes | |

| [1][2] | |

Major functions

The FAA's roles include:

Regulating U.S. commercial space transportation

Regulating air navigation facilities' geometric and flight inspection standards

Encouraging and developing civil aeronautics, including new aviation technology

Issuing, suspending, or revoking pilot certificates

Regulating civil aviation to promote transportation safety in the United States, especially through local offices called Flight Standards District Offices

Developing and operating a system of air traffic control and navigation for both civil and military aircraft

Researching and developing the National Airspace System and civil aeronautics

Developing and carrying out programs to control aircraft noise and other environmental effects of civil aviation

Organizations

The FAA is divided into four "lines of business" (LOB).[3] Each LOB has a specific role within the FAA.

Airports (ARP) [4] : plans and develops projects involving airports, overseeing their construction and operations. Ensures compliance with federal regulations.[4]

[5]]]]]Air Traffic Organization (ATO): primary duty is to safely and efficiently move air traffic within the National Airspace System. ATO employees manage air traffic facilities including Airport Traffic Control Towers (ATCT) and Terminal Radar Approach Control Facilities (TRACONs).[5] See also Airway Operational Support.

Aviation Safety (AVS) [6] : Responsible for aeronautical certification of personnel and aircraft, including pilots, airlines, and mechanics.[6]

Commercial Space Transportation (AST) [53] : ensures protection of U.S. assets during the launch or reentry of commercial space vehicles.[7]

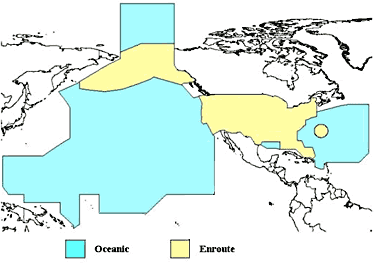

Regions and Aeronautical Center Operations

The FAA provides air traffic control services over U.S. territory and over international waters where it has been delegated such authority by the International Civil Aviation Organization. This map depicts overflight fee regions. Yellow (enroute) covers land territory, excluding Hawaii and some island territories but including most of the Bering Sea as well as Bermuda and The Bahamas (sovereign countries, where the FAA provides high-altitude ATC service). The blue regions are where the U.S. provides oceanic ATC services over international waters (Hawaii, some US island territories, & some small, foreign island nations/territories are included in this region).

The FAA is headquartered in Washington, D.C.[8] as well as the William J. Hughes Technical Center in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and its nine regional offices:

Alaskan Region – Anchorage, Alaska

Northwest Mountain – Seattle, Washington

Western Pacific – Los Angeles, California

Southwest – Fort Worth, Texas

Central – Kansas City, Missouri

Great Lakes – Chicago, Illinois

Southern – Atlanta, Georgia

Eastern – New York, New York

New England – Boston, Massachusetts

History

FAA Headquarters, Washington, D.C.

FAA Joint Surveillance Site radar, Canton, Michigan

The Air Commerce Act of May 20, 1926, is the cornerstone of the federal government's regulation of civil aviation. This landmark legislation was passed at the urging of the aviation industry, whose leaders believed the airplane could not reach its full commercial potential without federal action to improve and maintain safety standards. The Act charged the Secretary of Commerce with fostering air commerce, issuing and enforcing air traffic rules, licensing pilots, certifying aircraft, establishing airways, and operating and maintaining aids to air navigation. The newly created Aeronautics Branch, operating under the Department of Commerce assumed primary responsibility for aviation oversight.

In fulfilling its civil aviation responsibilities, the Department of Commerce initially concentrated on such functions as safety regulations and the certification of pilots and aircraft.

It took over the building and operation of the nation's system of lighted airways, a task initiated by the Post Office Department. The Department of Commerce improved aeronautical radio communications—before the founding of the Federal Communications Commission in 1934, which handles most such matters today—and introduced radio beacons as an effective aid to air navigation.

The Aeronautics Branch was renamed the Bureau of Air Commerce in 1934 to reflect its enhanced status within the Department.

As commercial flying increased, the Bureau encouraged a group of airlines to establish the first three centers for providing air traffic control (ATC) along the airways. In 1936, the Bureau itself took over the centers and began to expand the ATC system. The pioneer air traffic controllers used maps, blackboards, and mental calculations to ensure the safe separation of aircraft traveling along designated routes between cities.

In 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Act transferred the federal civil aviation responsibilities from the Commerce Department to a new independent agency, the Civil Aeronautics Authority. The legislation also expanded the government's role by giving the CAA the authority and the power to regulate airline fares and to determine the routes that air carriers would serve.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt split the authority into two agencies in 1940: the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). CAA was responsible for ATC, airman and aircraft certification, safety enforcement, and airway development. CAB was entrusted with safety regulation, accident investigation, and economic regulation of the airlines. The CAA was part of the Department of Commerce. The CAB was an independent federal agency.

On the eve of America's entry into World War II, CAA began to extend its ATC responsibilities to takeoff and landing operations at airports. This expanded role eventually became permanent after the war. The application of radar to ATC helped controllers in their drive to keep abreast of the postwar boom in commercial air transportation. In 1946, meanwhile, Congress gave CAA the added task of administering the federal-aid airport program, the first peacetime program of financial assistance aimed exclusively at development of the nation's civil airports.

The approaching era of jet travel, and a series of midair collisions (most notable was the 1956 Grand Canyon mid-air collision) prompted passage of the Federal Aviation Act of 1958. This legislation gave the CAA's functions to a new independent body, the Federal Aviation Agency. The act transferred air safety regulation from the CAB to the new FAA, and also gave the FAA sole responsibility for a common civil-military system of air navigation and air traffic control. The FAA's first administrator, Elwood R. Quesada, was a former Air Force general and adviser to President Eisenhower.

The same year witnessed the birth of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), created in the wake of the Soviets launching the first artificial satellite and assuming NACA's role of aeronautical research.

In 1967, a new U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) combined major federal responsibilities for air and surface transport. The Federal Aviation Agency's name changed to the Federal Aviation Administration as it became one of several agencies (e.g., Federal Highway Administration, Federal Railroad Administration, the Coast Guard, and the Saint Lawrence Seaway Commission) within DOT (albeit the largest). The FAA administrator would no longer report directly to the president but would instead report to the Secretary of Transportation. New programs and budget requests would have to be approved by DOT, which would then include these requests in the overall budget and submit it to the president.

At the same time, a new National Transportation Safety Board took over the Civil Aeronautics Board's (CAB) role of investigating and determining the causes of transportation accidents and making recommendations to the secretary of transportation. CAB was merged into DOT with its responsibilities limited to the regulation of commercial airline routes and fares.

The FAA gradually assumed additional functions.

The hijacking epidemic of the 1960s had already brought the agency into the field of civil aviation security.

In response to the hijackings on September 11, 2001, this responsibility is now primarily taken by the Department of Homeland Security. The FAA became more involved with the environmental aspects of aviation in 1968 when it received the power to set aircraft noise standards. Legislation in 1970 gave the agency management of a new airport aid program and certain added responsibilities for airport safety. During the 1960s and 1970s, the FAA also started to regulate high altitude (over 500 feet) kite and balloon flying.

By the mid-1970s, the agency had achieved a semi-automated air traffic control system using both radar and computer technology. This system required enhancement to keep pace with air traffic growth, however, especially after the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 phased out the CAB's economic regulation of the airlines. A nationwide strike by the air traffic controllers union in 1981 forced temporary flight restrictions but failed to shut down the airspace system. During the following year, the agency unveiled a new plan for further automating its air traffic control facilities, but progress proved disappointing. In 1994, the FAA shifted to a more step-by-step approach that has provided controllers with advanced equipment.[9]

In 1979, Congress authorized the FAA to work with major commercial airports to define noise pollution contours and investigate the feasibility of noise mitigation by residential retrofit programs. Throughout the 1980s, these charters were implemented.

In the 1990s, satellite technology received increased emphasis in the FAA's development programs as a means to improvements in communications, navigation, and airspace management.

In 1995, the agency assumed responsibility for safety oversight of commercial space transportation, a function begun eleven years before by an office within DOT headquarters.

The agency was responsible for the decision to ground flights after the September 11 attacks.

21st century

In December 2000, an organization within the FAA called the Air Traffic Organization,[10] (ATO) was set up by presidential executive order. This became the air navigation service provider for the airspace of the United States and for the New York (Atlantic) and Oakland (Pacific) oceanic areas. It is a full member of the Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation.

The FAA issues a number of awards to holders of its licenses.

Among these are demonstrated proficiencies as an aviation mechanic, a flight instructor, a 50-year aviator, or as a safe pilot.

The latter, the FAA "Wings Program", provides a series of three badges for pilots who have undergone several hours of training since their last award. For more information see "FAA Advisory Circular 61-91H".

On March 18, 2008, the FAA ordered its inspectors to reconfirm that airlines are complying with federal rules after revelations that Southwest Airlines flew dozens of aircraft without certain mandatory inspections.[11] The FAA exercises surprise Red Team drills on national airports annually.

On October 31, 2013, after outcry from media outlets, including heavy criticism [12] from Nick Bilton of The New York Times,[13][14] the FAA announced it will allow airlines to expand the passengers use of portable electronic devices during all phases of flight, but mobile phone calls would still be prohibited (and use of cellular networks during any point when aircraft doors are closes remains prohibited to-date). Implementation initially varied among airlines. The FAA expected many carriers to show that their planes allow passengers to safely use their devices in airplane mode, gate-to-gate, by the end of 2013. Devices must be held or put in the seat-back pocket during the actual takeoff and landing. Mobile phones must be in airplane mode or with mobile service disabled, with no signal bars displayed, and cannot be used for voice communications due to Federal Communications Commission regulations that prohibit any airborne calls using mobile phones. From a technological standpoint, cellular service would not work in-flight because of the rapid speed of the airborne aircraft: mobile phones cannot switch fastlt enough between cellular towers at an aircraft's high speed; however, the ban is did to potential radio interference with aircraft avionics. If an air carrier provides Wi-Fi service during flight, passengers may use it. Short-range Bluetooth accessories, like wireless keyboards, can also be used.[15]

In July 2014, in the wake of the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, the FAA suspended flights by U.S. airlines to Ben Gurion Airport during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict for 24 hours. The ban was extended for a further 24 hours but was lifted about six hours later.[16]

History of FAA Administrators

| Term start date | End date | Administrator | Status/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 Nov 1 | 1961 Jan 20 | Elwood Richard Quesada | |

| 1961 Mar 3 | 1965 Jul 1 | Najeeb Halaby | |

| 1965 Jul 1 | 1968 Jul 31 | William F. McKee | [20] |

| 1969 Mar 24 | 1973 Mar 14 | John H. Shaffer | [20] |

| 1973 Mar 14 | 1975 Mar 31 | Alexander Butterfield | |

| 1975 Nov 24 | 1977 Apr 1 | John L. McLucas | |

| 1977 Ma 4 | 1981 Jan 20 | Langhorne Bond | |

| 1981 Apr 22 | 1984 Jan 31 | J. Lynn Helms | |

| 1984 Apr 10 | 1987 Jul 2 | Donald D. Engen | |

| 1987 Jul 22 | 1989 Feb 17 | T. Allan McArtor | |

| 1989 Jun 30 | 1991 Dec 4 | James B. Busey IV | |

| 1992 Jun 27 | 1993 Jan 20 | Thomas C. Richards | |

| 1993 Aug 10 | 1996 Nov 9 | David R. Hinson | |

| 1997 Aug 4 | 2002 Aug 2 | Jane Garvey | |

| 2002 Sep 12 | 2007 Sep 13 | Marion Blakey | |

| 2007 Sep 14 | 2009 Jan 15 | Robert A. Sturgell | (acting) |

| 2009 Jan 16 | 2009 May 31 | Lynne Osmus | (acting) |

| 2009 Jun 1 | 2011 Dec 6 | Randy Babbitt | |

| 2011 Dec 7 | 2018 Jan 6 | Michael Huerta | |

| 2018 Jan 6 | 2019 Aug 12 | Daniel K. Elwell | (acting)[21][22][23] |

| 2019 Aug 12 | present | Stephen Dickson |

On March 19, 2019, President Donald Trump announced he would nominate Stephen Dickson, a former executive and pilot at Delta Air Lines, to be the next FAA Administrator.[24][22][23] On July 24, 2019, the Senate confirmed Dickson by a vote of 52-40.[25][26] He was sworn in as Administrator by Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao on August 12, 2019.[26]

Criticism

Conflicting roles

The FAA has been cited as an example of regulatory capture, "in which the airline industry openly dictates to its regulators its governing rules, arranging for not only beneficial regulation, but placing key people to head these regulators."[27] Retired NASA Office of Inspector General Senior Special Agent Joseph Gutheinz, who used to be a Special Agent with the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Transportation and with FAA Security, is one of the most outspoken critics of FAA. Rather than commend the agency for proposing a $10.2 million fine against Southwest Airlines for its failure to conduct mandatory inspections in 2008, he was quoted as saying the following in an Associated Press story: "Penalties against airlines that violate FAA directives should be stiffer. At $25,000 per violation, Gutheinz said, airlines can justify rolling the dice and taking the chance on getting caught. He also said the FAA is often too quick to bend to pressure from airlines and pilots."[28] Other experts have been critical of the constraints and expectations under which the FAA is expected to operate. The dual role of encouraging aerospace travel and regulating aerospace travel are contradictory. For example, to levy a heavy penalty upon an airline for violating an FAA regulation which would impact their ability to continue operating would not be considered encouraging aerospace travel.

On July 22, 2008, in the aftermath of the Southwest Airlines inspection scandal, a bill was unanimously approved in the House to tighten regulations concerning airplane maintenance procedures, including the establishment of a whistleblower office and a two-year "cooling off" period that FAA inspectors or supervisors of inspectors must wait before they can work for those they regulated.[29][30] The bill also required rotation of principal maintenance inspectors and stipulated that the word "customer" properly applies to the flying public, not those entities regulated by the FAA.[29] The bill died in a Senate committee that year.[31]

In September 2009, the FAA administrator issued a directive mandating that the agency use the term "customers" to refer to only the flying public.[32]

Lax regulatory oversight

In 2007, two FAA whistleblowers, inspectors Charalambe "Bobby" Boutris and Douglas E. Peters, alleged that Boutris said he attempted to ground Southwest after finding cracks in the fuselage of an aircraft, but was prevented by supervisors he said were friendly with the airline.[33] This was validated by a report by the Department of Transportation which found FAA managers had allowed Southwest Airlines to fly 46 airplanes in 2006 and 2007 that were overdue for safety inspections, ignoring concerns raised by inspectors. Audits of other airlines resulted in two airlines grounding hundreds of planes, causing thousands of flight cancellations.[29] The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee held hearings in April 2008. Jim Oberstar, former chairman of the committee, said its investigation uncovered a pattern of regulatory abuse and widespread regulatory lapses, allowing 117 aircraft to be operated commercially although not in compliance with FAA safety rules [69].[33] Oberstar said there was a "culture of coziness" between senior FAA officials and the airlines and "a systematic breakdown" in the FAA's culture that resulted in "malfeasance, bordering on corruption".[33] In 2008 the FAA proposed to fine Southwest $10.2 million for failing to inspect older planes for cracks,[28] and in 2009 Southwest and the FAA agreed that Southwest would pay a $7.5 million penalty and would adopt new safety procedures, with the fine doubling if Southwest failed to follow through.[34]

Changes to air traffic controller application process

In 2014, the FAA modified its approach to air traffic control hiring.

It launched more "off the street bids", allowing anyone with either a four-year degree or five years of full-time work experience to apply, rather than the closed college program or VRA bids, something that had last been done in 2008.

Thousands have been picked up, including veterans, CTI grads, and people who are true "off the street" hires.

The move was made to open the job up to more people who might make good controllers but did not go to a college that offered a CTI program.

Before the change, candidates who had completed coursework at participating colleges and universities could be "fast-tracked" for consideration.

However, the CTI program had no guarantee of a job offer, nor was the goal of the program to teach people to work actual traffic.

The goal of the program was to prepare people for the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, OK.

Having a CTI certificate allowed a prospective controller to skip the Air Traffic Basics part of the academy, about a 30- to 45-day course, and go right into Initial Qualification Training (IQT).

All prospective controllers, CTI or not, have had to pass the FAA Academy in order to be hired as a controller.

Failure at the academy means FAA employment is terminated.

In January 2015 they launched another pipeline, a "prior experience" bid, where anyone with an FAA Control Tower Operator certificate (CTO) and 52 weeks of experience could apply.

This was a revolving bid, every month the applicants on this bid were sorted out, and eligible applicants were hired and sent directly to facilities, bypassing the FAA academy entirely.

In the process of promoting diversity, the FAA revised its hiring process.[35][36] The FAA later issued a report that the "bio-data" was not a reliable test for future performance. However, the "Bio-Q" was not the determinating factor for hiring, it was merely a screening tool to determine who would take a revised Air Traffic Standardized Aptitude Test (ATSAT). Due to cost and time, it was not practical to give all 30,000 some applicants the revised ATSAT, which has since been validated. In 2015 Fox News levied unsubstantiated criticism that the FAA discriminated against qualified candidates.[37]

In December 2015, a reverse discrimination lawsuit was filed against the FAA seeking class-action status for the thousands of men and women who spent up to $40,000 getting trained under FAA rules before they were abruptly changed.

The prospects of the lawsuit are unknown, as the FAA is a self-governing entity and therefore can alter and experiment with its hiring practices, and there was never any guarantee of a job in the CTI program.[38]

Boeing 737 MAX crisis

As a result of the March 10, 2019 Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crash and the Lion Air Flight 610 crash five months earlier, most airlines and countries began grounding the Boeing 737 MAX 8 (and in many cases all MAX variants) due to safety concerns, but the FAA declined to temporarily ground Boeing 737 Max 8 aircraft operating in the U.S.[39] On March 12, the FAA said that its ongoing review showed "no systemic performance issues and provides no basis to order grounding the aircraft."[40] Some U.S. Senators called for the FAA to ground the aircraft until an investigation into the cause of the Ethiopian Airlines crash was complete.[40] U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao said that "If the FAA identifies an issue that affects safety, the department will take immediate and appropriate action."[41] On March 13, President Donald Trump announced that all Boeing 737 MAX airplanes within U.S. territory would be grounded, and the FAA issued the official order, citing new evidence of similarity between the two accidents. Three major U.S. airlines--Southwest, United, and American Airlines—were affected by this decision.[42]

Regulatory process

Designated Engineering Representative

A Designated Engineering Representative (DER) is an engineer who is appointed under 14 CFR section 183.29 to act on behalf of a company or as an independent consultant (IC).[43]

Company DERs act on behalf of their employer and may only approve, or recommend that the FAA approves, technical data produced by their employer.

Consultant DERs are appointed to act as independent DERs and may approve, or recommend that the FAA approves, technical data produced by any person or organization.

Designated Airworthiness Representative (DAR)

A DAR[44] is an individual appointed in accordance with 14 CFR 183.33 who may perform examination, inspection, and testing services necessary to the issuance of certificates.

There are two types of DARs: manufacturing, and maintenance.

Manufacturing DARs must possess aeronautical knowledge, experience, and meet the qualification requirements of Order 8100.8.

Maintenance DARs must hold: a mechanic's certificate with an airframe and powerplant rating, under 14 CFR part 65 Certification: Airmen Other Than Flight Crewmembers, or a repairman certificate and be employed at a repair station certificated under 14 CFR part 145, or an air carrier operating certificate holder with an FAA-approved continuous airworthiness program, and must meet the qualification requirements of FAA Order 8100.8, Chapter 14.

Specialized Experience – Amateur-Built and Light-Sport Aircraft DARs Both Manufacturing DARs and Maintenance DARs may be authorized to perform airworthiness certification of light-sport aircraft.

DAR qualification criteria and selection procedures for amateur-built and light-sport aircraft airworthiness functions are provided in Order 8100.8.

Proposed regulatory reforms

FAA reauthorization and air traffic control reform

U.S. law requires that the FAA's budget and mandate be reauthorized on a regular basis.

On July 18, 2016, President Obama signed a second short-term extension of the FAA authorization, replacing a previous extension that was due to expire that day.[45]

The 2016 extension (set to expire itself in September 2017) left out a provision pushed by Republican House leadership, including House Transportation and Infrastructure (T&I) Committee Chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA). The provision would have moved authority over air traffic control from the FAA to a non-profit corporation, as many other nations, such as Canada, Germany and the United Kingdom, have done.[46] Shuster's bill, the Aviation Innovation, Reform, and Reauthorization (AIRR) Act,[47] expired in the House at the end of the 114th Congress.[48]

The House T&I Committee began the new reauthorization process for the FAA in February 2017.

It is expected that the committee will again urge Congress to consider and adopt air traffic control reform as part of the reauthorization package.

Shuster has additional support from President Trump, who, in a meeting with aviation industry executives in early 2017 said the U.S. air control system is "....totally out of whack."[49]

See also

Acquisition Management System

Federal Aviation Regulations

National aviation authority (generic term)

Office of Dispute Resolution for Acquisition

SAFO, Safety Alert for Operators

United States government role in civil aviation

Weather Information Exchange Model