Client–server model

Client–server model

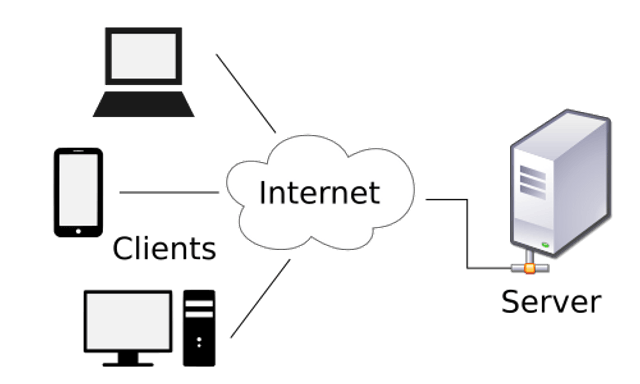

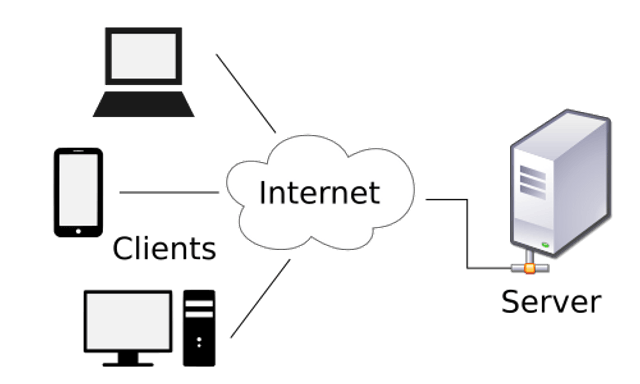

Client–server model is a distributed application structure that partitions tasks or workloads between the providers of a resource or service, called servers, and service requesters, called clients.[1] Often clients and servers communicate over a computer network on separate hardware, but both client and server may reside in the same system. A server host runs one or more server programs which share their resources with clients. A client does not share any of its resources, but requests a server's content or service function. Clients therefore initiate communication sessions with servers which await incoming requests. Examples of computer applications that use the client–server model are Email, network printing, and the World Wide Web.

Client and server role

The client-server characteristic describes the relationship of cooperating programs in an application. The server component provides a function or service to one or many clients, which initiate requests for such services. Servers are classified by the services they provide. For example, a web server serves web pages and a file server serves computer files. A shared resource may be any of the server computer's software and electronic components, from programs and data to processors and storage devices. The sharing of resources of a server constitutes a service.

Whether a computer is a client, a server, or both, is determined by the nature of the application that requires the service functions. For example, a single computer can run web server and file server software at the same time to serve different data to clients making different kinds of requests. Client software can also communicate with server software within the same computer.[2] Communication between servers, such as to synchronize data, is sometimes called inter-server or server-to-server communication.

Client and server communication

In general, a service is an abstraction of computer resources and a client does not have to be concerned with how the server performs while fulfilling the request and delivering the response. The client only has to understand the response based on the well-known application protocol, i.e. the content and the formatting of the data for the requested service.

Clients and servers exchange messages in a request–response messaging pattern. The client sends a request, and the server returns a response. This exchange of messages is an example of inter-process communication. To communicate, the computers must have a common language, and they must follow rules so that both the client and the server know what to expect. The language and rules of communication are defined in a communications protocol. All client-server protocols operate in the application layer. The application layer protocol defines the basic patterns of the dialogue. To formalize the data exchange even further, the server may implement an application programming interface (API).[3] The API is an abstraction layer for accessing a service. By restricting communication to a specific content format, it facilitates parsing. By abstracting access, it facilitates cross-platform data exchange.[4]

A server may receive requests from many distinct clients in a short period of time. A computer can only perform a limited number of tasks at any moment, and relies on a scheduling system to prioritize incoming requests from clients to accommodate them. To prevent abuse and maximize availability, server software may limit the availability to clients. Denial of service attacks are designed to exploit a server's obligation to process requests by overloading it with excessive request rates.

Example

When a bank customer accesses online banking services with a web browser (the client), the client initiates a request to the bank's web server. The customer's login credentials may be stored in a database, and the web server accesses the database server as a client. An application server interprets the returned data by applying the bank's business logic, and provides the output to the web server. Finally, the web server returns the result to the client web browser for display.

In each step of this sequence of client–server message exchanges, a computer processes a request and returns data. This is the request-response messaging pattern. When all the requests are met, the sequence is complete and the web browser presents the data to the customer.

This example illustrates a design pattern applicable to the client–server model: separation of concerns.

Early history

An early form of client–server architecture is remote job entry, dating at least to OS/360 (announced 1964), where the request was to run a job, and the response was the output.

While formulating the client–server model in the 1960s and 1970s, computer scientists building ARPANET (at the Stanford Research Institute) used the terms server-host (or serving host) and user-host (or using-host), and these appear in the early documents RFC 5 [16] [5] and RFC 4 [17] .[6] This usage was continued at Xerox PARC in the mid-1970s.

One context in which researchers used these terms was in the design of a computer network programming language called Decode-Encode Language (DEL).[5] The purpose of this language was to accept commands from one computer (the user-host), which would return status reports to the user as it encoded the commands in network packets. Another DEL-capable computer, the server-host, received the packets, decoded them, and returned formatted data to the user-host. A DEL program on the user-host received the results to present to the user. This is a client–server transaction. Development of DEL was just beginning in 1969, the year that the United States Department of Defense established ARPANET (predecessor of Internet).

Client-host and server-host

Client-host and server-host have subtly different meanings than client and server. A host is any computer connected to a network. Whereas the words server and client may refer either to a computer or to a computer program, server-host and user-host always refer to computers. The host is a versatile, multifunction computer; clients and servers are just programs that run on a host. In the client–server model, a server is more likely to be devoted to the task of serving.

An early use of the word client occurs in "Separating Data from Function in a Distributed File System", a 1978 paper by Xerox PARC computer scientists Howard Sturgis, James Mitchell, and Jay Israel. The authors are careful to define the term for readers, and explain that they use it to distinguish between the user and the user's network node (the client).[7] (By 1992, the word server had entered into general parlance.)[8][9]

Centralized computing

The client–server model does not dictate that server-hosts must have more resources than client-hosts. Rather, it enables any general-purpose computer to extend its capabilities by using the shared resources of other hosts. Centralized computing, however, specifically allocates a large amount of resources to a small number of computers. The more computation is offloaded from client-hosts to the central computers, the simpler the client-hosts can be.[10] It relies heavily on network resources (servers and infrastructure) for computation and storage. A diskless node loads even its operating system from the network, and a computer terminal has no operating system at all; it is only an input/output interface to the server. In contrast, a fat client, such as a personal computer, has many resources, and does not rely on a server for essential functions.

As microcomputers decreased in price and increased in power from the 1980s to the late 1990s, many organizations transitioned computation from centralized servers, such as mainframes and minicomputers, to fat clients.[11] This afforded greater, more individualized dominion over computer resources, but complicated information technology management.[10][12][13] During the 2000s, web applications matured enough to rival application software developed for a specific microarchitecture. This maturation, more affordable mass storage, and the advent of service-oriented architecture were among the factors that gave rise to the cloud computing trend of the 2010s.[14]

Comparison with peer-to-peer architecture

In addition to the client–server model, distributed computing applications often use the peer-to-peer (P2P) application architecture.

In the client–server model, the server is often designed to operate as a centralized system that serves many clients. The computing power, memory and storage requirements of a server must be scaled appropriately to the expected work-load (i.e., the number of clients connecting simultaneously). Load-balancing and failover systems are often employed to scale the server implementation.

In a peer-to-peer network, two or more computers (peers) pool their resources and communicate in a decentralized system. Peers are coequal, or equipotent nodes in a non-hierarchical network. Unlike clients in a client–server or client–queue–client network, peers communicate with each other directly. In peer-to-peer networking, an algorithm in the peer-to-peer communications protocol balances load, and even peers with modest resources can help to share the load. If a node becomes unavailable, its shared resources remain available as long as other peers offer it. Ideally, a peer does not need to achieve high availability because other, redundant peers make up for any resource downtime; as the availability and load capacity of peers change, the protocol reroutes requests.

Both client-server and master-slave are regarded as sub-categories of distributed peer-to-peer systems.[15]

See also

Front and back ends

Modular programming

Observer pattern

Publish–subscribe pattern

Pull technology

Push technology

Remote procedure call