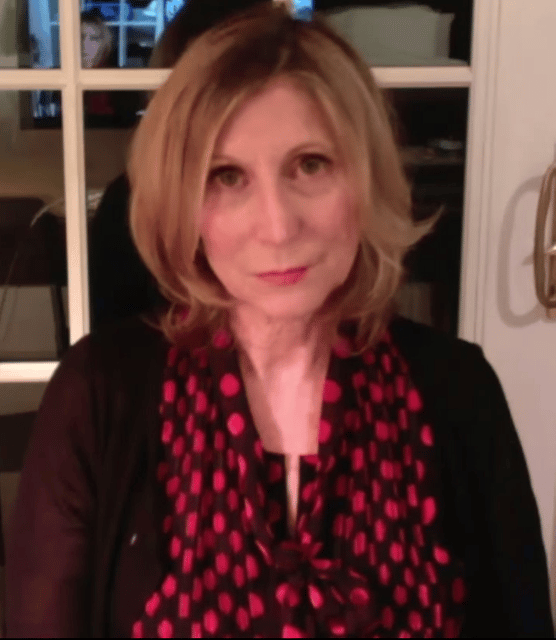

Christina Hoff Sommers

Christina Hoff Sommers

| Born | Christina Marie HoffSeptember 28, 1950Sonoma,California, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Author, philosopher, university professor, scholar at theAmerican Enterprise Institute |

| Alma mater | New York UniversityBrandeis University |

| Notable works | Who Stole Feminism?,The War Against Boys,Vice and Virtue in Everyday Life |

| Spouse | Frederic Tamler Sommers(widowed) |

| Website | |

Christina Marie Hoff Sommers (born September 28, 1950) is an American author and philosopher. Specializing in ethics, she is currently a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.[2][3][4][5][6] Sommers is known for her critique of contemporary feminism.[7][8][9] Her work includes the books Who Stole Feminism? (1994) and The War Against Boys (2000). She also hosts a video blog called The Factual Feminist.

Sommers' positions and writing have been characterized by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as "equity feminism", a classical-liberal or libertarian feminist perspective holding that the main political role of feminism is to ensure that the right against coercive interference is not infringed.[10] Sommers has contrasted equity feminism with what she terms victim feminism and gender feminism,[11][12] arguing that modern feminist thought often contains an "irrational hostility to men" and possesses an "inability to take seriously the possibility that the sexes are equal but different".[11]

| Born | Christina Marie HoffSeptember 28, 1950Sonoma,California, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Author, philosopher, university professor, scholar at theAmerican Enterprise Institute |

| Alma mater | New York UniversityBrandeis University |

| Notable works | Who Stole Feminism?,The War Against Boys,Vice and Virtue in Everyday Life |

| Spouse | Frederic Tamler Sommers(widowed) |

| Website | |

Early life

Career

Ideas and views

Sommers said in 2014 that she is a registered Democrat "with libertarian leanings".[16] She has described herself as an equity feminist,[17][18][19] equality feminist,[20][21] and liberal feminist,[22][23] and defines equity feminism as the struggle, based upon Enlightenment principles of individual justice,[24] for equal legal and civil rights for women, the original goals of first-wave feminism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy categorizes equity feminism as libertarian or classically liberal.[10]

Several authors have called Sommers' positions antifeminist.[25][26][27] The feminist philosopher Alison Jaggar wrote in 2006 that, in rejecting the theoretical distinction between sex as a set of physiological traits and gender as a set of social identities, "Sommers rejected one of the distinctive conceptual innovations of second wave Western feminism", and that as the concept of gender is relied on by "virtually all" modern feminists, "the conclusion that Sommers is an anti-feminist instead of a feminist is difficult to avoid".[23]

Sommers is a longtime critic of women's studies departments, and of university curricula in general. In a 1995 interview with freelance journalist Scott London, Sommers said, "The perspective now, from my point of view, is that the better things get for women, the angrier the women's studies professors seem to be, the more depressed Gloria Steinem seems to get."[28] According to The Nation, Sommers would tell her students that "statistically challenged" feminists in women's studies departments engage in "bad scholarship to advance their liberal agenda" and are peddling a skewed and incendiary message: "Women are from Venus, men are from Hell."[29]

Sommers has written about Title IX and the shortage of women in STEM fields. She opposes recent efforts to apply Title IX to the sciences[30] because "Science is not a sport. In science, men and women play on the same teams.... There are many brilliant women in the top ranks of every field of science and technology, and no one doubts their ability to compete on equal terms."[31] Sommers writes that Title IX programs in the sciences could stigmatize women and cheapen their hard-earned achievements. She adds that personal preference, not sexist discrimination, plays a role in women's career choices.[32] Sommers believes that not only do women favor fields like biology, psychology, and veterinary medicine over physics and mathematics, but they also seek out more family-friendly careers. She has written that "the real problem most women scientists confront is the challenge of combining motherhood with a high-powered science career."[31]

Early work

From 1978 to 1980, Sommers was an instructor at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. In 1980, she became an assistant professor of philosophy at Clark University and was promoted to associate professor in 1986. Sommers remained at Clark until 1997, when she became the W.H. Brady fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.[15] During the mid-1980s, Sommers edited two philosophy textbooks on the subject of ethics: Vice & Virtue in Everyday Life: Introductory Readings in Ethics (1984) and Right and Wrong: Basic Readings in Ethics (1986). Reviewing Vice and Virtue for Teaching Philosophy in 1990, Nicholas Dixon wrote that the book was "extremely well edited" and "particularly strong on the motivation for studying virtue and ethics in the first place, and on theoretical discussions of virtue and vice in general."[35]

Beginning in the late 1980s, Sommers published a series of articles in which she strongly criticized feminist philosophers and American feminism in general.[36][37] In a 1988 Public Affairs Quarterly article titled "Should the Academy Support Academic Feminism?", Sommers wrote that "the intellectual and moral credentials of academic feminism badly want scrutiny" and asserted that "the tactics used by academic feminists have all been employed at one time or another to further other forms of academic imperialism."[38] In articles titled "The Feminist Revelation" and "Philosophers Against the Family," which she published during the early 1990s, Sommers argued that many academic feminists were "radical philosophers" who sought dramatic social and cultural change—such as the abolition of the nuclear family—and thus revealed their contempt for the actual wishes of the "average woman."[39][40][41] These articles would form the basis for Who Stole Feminism?[41]

Other work

Sommers is a member of the Board of Advisors of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education.[42] She has served on the national advisory board of the Independent Women's Forum[43] and the Center of the American Experiment.[44] Sommers has written articles for Time,[45] The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times.[46] She hosts a video blog called The Factual Feminist on YouTube.[47][48] Sommers created a video "course" for the conservative website Prager University.[49]

Who Stole Feminism?

In Who Stole Feminism, Sommers outlines her distinction between gender feminism,[1] which she regards as being the dominant contemporary approach to feminism, and equity feminism, which she presents as more akin to first-wave feminism. She uses the work to argue that contemporary feminism is too radical and disconnected from the lives of typical American women, presenting her equity feminism alternative as a better match for their needs.[51] She characterizes gender feminism as having transcended the liberalism of early feminists so that instead of focusing on rights for all, gender feminists view society through the sex/gender prism and focus on recruiting women to join the struggle against patriarchy.[52]%2C%20p.%2023.]] Reason Who Stole Feminism?: How Women Have Betrayed Womenharacterized gender feminism as the action of accenting the differences of genders in order to create what Sommers believes is privilege for women in academia, government, industry, or the advancement of personal agendas.[53][54]

In criticizing contemporary feminism, Sommers writes that an often-mentioned March of Dimes study which says that "domestic violence is the leading cause of birth defects", does not exist, and that violence against women does not peak during the Super Bowl, which she describes as an urban legend, arguing that such statements about domestic violence helped shape the Violence Against Women Act, which initially allocated $1.6 billion a year in federal funds for ending domestic violence against women. Similarly, she argues[55] that feminists assert that approximately 150,000 women die each year from anorexia, an apparent distortion of the American Anorexia and Bulimia Association [86] 's figure that 150,000 females have some degree of anorexia.[56][57]

Laura Flanders of the Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), panned Sommers's book as being "filled with the same kind of errors, unsubstantiated charges and citations of 'advocacy research' that she claims to find in the work of the feminists she takes to task..."[56] Sommers responded to FAIR's criticisms in a letter to the editor of FAIR's monthly magazine, EXTRA! [58]

The War Against Boys

In 2000, Sommers published The War Against Boys: How Misguided Feminism Is Harming Our Young Men. In the book, Sommers challenged what she called the "myth of shortchanged girls" and the "new and equally corrosive fiction" that "boys as a group are disturbed."[59] Criticizing programs which had been set up in the 1980s to encourage girls and young women - largely in response to studies which had suggested that girls "suffered through neglect in the classroom and the indifference of male-dominated society"[60] - Sommers argued in The War Against Boys that such programs were based on flawed research, arguing that it was just the other way around: boys were a year and a half behind girls in reading and writing and less likely to go to college.

She blamed Carol Gilligan as well as organizations such as the National Organization for Women (NOW)[60] for creating a situation in which "boys are resented, both as the unfairly privileged sex and as obstacles on the path to gender justice for girls." According to Sommers, "a review of the facts shows boys, not girls, on the weak side of an education gender gap."[15][61]

Sommers wrote, "We are turning against boys and forgetting a simple truth: that the energy, competitiveness, and corporal daring of normal, decent males is responsible for much of what is right in the world."[62] Australian cultural studies professor Tara Brabazon wrote that with these words, "Sommers becomes the ventriloquist's dummy for male educational professors."[63]

The book received mixed reviews.

In conservative publications such as the National Review and Commentary, The War Against Boys was praised for its "stinging indictment of an anti-male movement that has had a pervasive influence on the nation's schools."[64]National%20Review]]nd for identifying "a problem in urgent need of redress."[65] Writing in The New York Times Richard Bernstein called it a "thoughtful, provocative book," and suggested that Sommers had made her arguments "persuasively and unflinchingly, and with plenty of data to support them."[66] Joy Summers, in The Journal of School Choice, said that 'Sommers’ book and her public voice are in themselves a small antidote to the junk science girding our typically commonsense-free, utterly ideological national debate on “women’s issues.' [67] Publishers Weekly* suggested that Sommers' conclusions were "compelling" and "deserve an unbiased hearing," while also noting that Sommers "descends into pettiness when she indulges in mudslinging at her opponents."[59] Similarly, a review in Booklist suggested that while Sommers "argues cogently that boys are having major problems in school," the book was unlikely to convince all readers "that these problems are caused by the American Association of University Women, Carol Gilligan, Mary Pipher, and William S. Pollack," all of whom were strongly criticized in the book. Ultimately, the review suggested, "Sommers is as much of a crisismonger as those she critiques."[68]

In a review of The War Against Boys for The New York Times, child psychiatrist Robert Coles wrote that Sommers "speaks of our children, yet hasn't sought them out; instead she attends those who have, in fact, worked with boys and girls--and in so doing is quick to look askance at Carol Gilligan's ideas about girls, [William] Pollack's about boys." Much of the book, according to Coles, "comes across as Sommers's strongly felt war against those two prominent psychologists, who have spent years trying to learn how young men and women grow to adulthood in the United States."[15][69] Reviewing the book for The New Yorker, Nicholas Lemann wrote that Sommers "sets the research bar considerably higher for the people she is attacking than she does for herself," using an "odd, ambushing style of refutation, in which she demands that data be provided to her and questions answered, and then, when the flummoxed person on the other end of the line stammers helplessly, triumphantly reports that she got 'em." Lemann faulted Sommers for accusing Gilligan of using anecdotal argument when her own book "rests on an anecdotal base," and for making numerous assertions that were not supported by the footnotes in her book.[70]

Writing in The Washington Post, E. Anthony Rotundo stated that "in the end, Sommers... does not show that there is a 'war against boys.' All she can show is that feminists are attacking her 'boys-will-be-boys' concept of boyhood, just as she attacks their more flexible notion." Sommers's title, according to Rotundo, "is not just wrong but inexcusably misleading... a work of neither dispassionate social science nor reflective scholarship; it is a conservative polemic."[71]

Awards

The National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC) awarded Sommers with one of its twelve 2013 Exceptional Merit in Media Awards[72] for her The New York Times article “The Boys at the Back.”[73] In their description of the winners, NWPC states, "Author Christina Sommers asks whether we should allow girls to reap the advantages of a new knowledge based service economy and take the mantle from boys, or should we acknowledge the roots of feminism and strive for equal education for all?"[72]

Personal life

See also

Egalitarianism

Equality before the law

Male privilege

Individualist feminism

Selected works

Books

(1984).

(ed.). Vice & Virtue in Everyday Life: Introductory Readings in Ethics. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Co-edited with Robert J. Fogelin for the 2nd and 3rd editions, and with Fred Sommers for the 4th and subsequent editions. ISBN 0155948903

(1986) (ed.). Right and Wrong: Basic Readings in Ethics. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Co-edited with Robert J. Fogelin. ISBN 0-15-577110-8

(1994). Who Stole Feminism?: How Women Have Betrayed Women. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84956-0

(2000 and 2013).

The War Against Boys. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84956-9 and ISBN 978-1-451-64418-0

(2005).

(with Sally Satel, M.D.). One Nation Under Therapy. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-30444-7

(2009).

The Science on Women in Science. Washington, D.C.: AEI Press. ISBN 978-0-8447-4281-6

(2013). Freedom Feminism: Its Surprising History and Why It Matters Today. Washington, D.C.: AEI Press. ISBN 978-0-844-77262-2

Articles

(1988). "Should the Academy Support Academic Feminism?".

Public Affairs Quarterly. 2: 97–120.

(1990). "The Feminist Revelation".

Social Philosophy and Policy. 8(1): 152–157.

(1990). "Do These feminists Like Women?".

Journal of Social Philosophy. 21(2) (Fall): 66–74.