Canon law

Canon law

Canon law (from Greek kanon, a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (Church leadership), for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law, or operational policy, governing the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Churches), the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, and the individual national churches within the Anglican Communion.[1] The way that such church law is legislated, interpreted and at times adjudicated varies widely among these three bodies of churches. In all three traditions, a canon was originally[2] a rule adopted by a church council; these canons formed the foundation of canon law.

Etymology

Canons of the Apostles

The Apostolic Canons[4] or Ecclesiastical Canons of the Same Holy Apostles[5] is a collection of ancient ecclesiastical decrees (eighty-five in the Eastern, fifty in the Western Church) concerning the government and discipline of the Early Christian Church, incorporated with the Apostolic Constitutions which are part of the Ante-Nicene Fathers. In the Fourth century the First Council of Nicaea (325) calls canons the disciplinary measures of the Church: the term canon, κανὠν, means in Greek, a rule. There is a very early distinction between the rules enacted by the Church and the legislative measures taken by the State called leges, Latin for laws.[6]

Catholic Church

In the Catholic Church, canon law is the system of laws and legal principles made and enforced by the Church's hierarchical authorities to regulate its external organization and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics toward the mission of the Church.[7]

In the Latin Church, positive ecclesiastical laws, based directly or indirectly upon immutable divine law or natural law, derive formal authority in the case of universal laws from the supreme legislator (i.e., the Supreme Pontiff), who possesses the totality of legislative, executive, and judicial power in his person,[8] while particular laws derive formal authority from a legislator inferior to the supreme legislator. The actual subject material of the canons is not just doctrinal or moral in nature, but all-encompassing of the human condition.[9]

The Catholic Church also includes the main five rites (groups) of churches which are in full union with the Holy See and the Latin Church:

Alexandrian Rite Churches which include the Coptic Catholic Church and Ethiopian Catholic Church.

West Syriac Rite which includes the Maronite Church, Syriac Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

Armenian Rite Church which includes the Armenian Catholic Church.

Byzantine Rite Churches which include the Albanian Greek Catholic Church, Belarusian Greek Catholic Church, Bulgarian Church, Byzantine Catholic Church of Croatia and Serbia, Greek Church, Hungarian Greek Catholic Church, Italo-Albanian Church, Macedonian Greek Catholic Church, Melkite Church, Romanian Church United with Rome, Greek-Catholic, Russian Church, Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church, Slovak Greek Catholic Church and Ukrainian Catholic Church.

East Syriac Rite Churches which includes the Chaldean Church and Syro-Malabar Church.

All of these church groups are in full communion with the Supreme Pontiff and are subject to the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches.

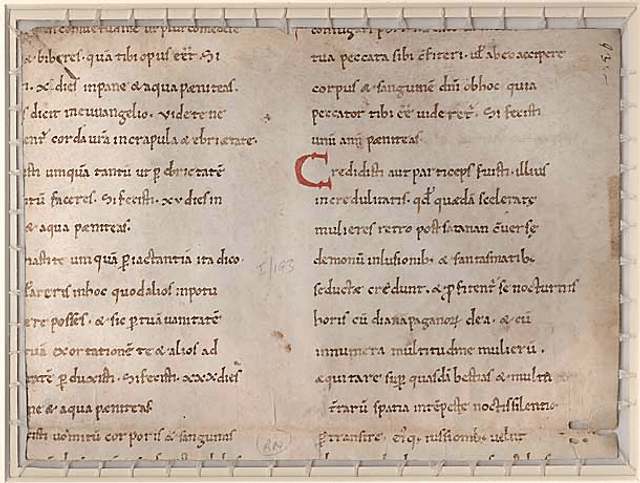

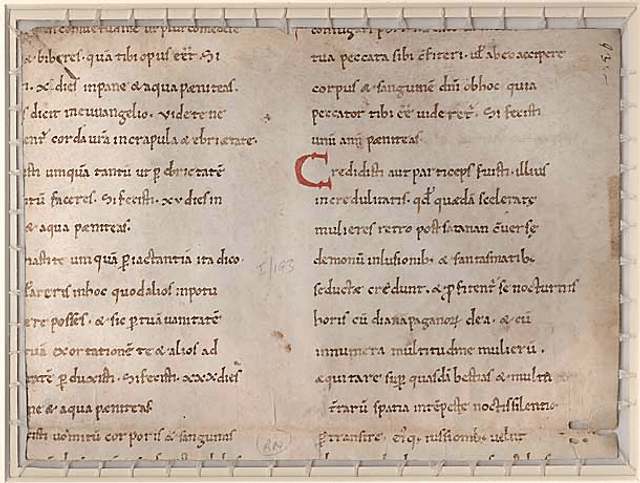

History, sources of law, and codifications

The Catholic Church has what is claimed to be the oldest continuously functioning internal legal system in Western Europe,[10] much later than Roman law but predating the evolution of modern European civil law traditions. What began with rules ("canons") adopted by the Apostles at the Council of Jerusalem in the first century has developed into a highly complex legal system encapsulating not just norms of the New Testament, but some elements of the Hebrew (Old Testament), Roman, Visigothic, Saxon, and Celtic legal traditions.

The history of Latin canon law can be divided into four periods: the jus antiquum, the jus novum, the jus novissimum and the Code of Canon Law.[11] In relation to the Code, history can be divided into the jus vetus (all law before the Code) and the jus novum (the law of the Code, or jus codicis).[11]

The canon law of the Eastern Catholic Churches, which had developed some different disciplines and practices, underwent its own process of codification, resulting in the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches promulgated in 1990 by Pope John Paul II.[12]

Catholic canon law as legal system

Roman canon law is a fully developed legal system, with all the necessary elements: courts, lawyers, judges, a fully articulated legal code[13] principles of legal interpretation, and coercive penalties, though it lacks civilly-binding force in most secular jurisdictions. One example where it did not previously apply was in the English legal system, as well as systems, such as the U.S., that derived from it. Here criminals could apply for the Benefit of clergy. Being in holy orders, or fraudulently claiming to be, meant that criminals could opt to be tried by ecclesiastical rather than secular courts. The ecclesiastical courts were generally more lenient. Under the Tudors, the scope of clerical benefit was steadily reduced by Henry VII, Henry VIII, and Elizabeth I. The Vatican disputed secular authority over priests' criminal offences, and this in turn contributed to the English Reformation. The benefit of clergy was systematically removed from English legal systems over the next 200 years, although it still occurred in South Carolina in 1827.

The structure that the fully developed Roman Law provides is a contribution to the Canon Law.[14] The academic degrees in canon law are the J.C.B. (Juris Canonici Baccalaureatus, Bachelor of Canon Law, normally taken as a graduate degree), J.C.L. (Juris Canonici Licentiatus, Licentiate of Canon Law) and the J.C.D. (Juris Canonici Doctor, Doctor of Canon Law). Because of its specialized nature, advanced degrees in civil law or theology are normal prerequisites for the study of canon law.

Much of the legislative style was adapted from the Roman Law Code of Justinian. As a result, Roman ecclesiastical courts tend to follow the Roman Law style of continental Europe with some variation, featuring collegiate panels of judges and an investigative form of proceeding, called "inquisitorial", from the Latin "inquirere", to enquire. This is in contrast to the adversarial form of proceeding found in the common law system of English and U.S. law, which features such things as juries and single judges.

The institutions and practices of canon law paralleled the legal development of much of Europe, and consequently both modern civil law and common law bear the influences of canon law. Edson Luiz Sampel, a Brazilian expert in canon law, says that canon law is contained in the genesis of various institutes of civil law, such as the law in continental Europe and Latin American countries. Sampel explains that canon law has significant influence in contemporary society.[15]

Canonical jurisprudential theory generally follows the principles of Aristotelian-Thomistic legal philosophy.[10] While the term "law" is never explicitly defined in the Code,[16] the Catechism of the Catholic Church cites Aquinas in defining law as "...an ordinance of reason for the common good, promulgated by the one who is in charge of the community"[17] and reformulates it as "...a rule of conduct enacted by competent authority for the sake of the common good."[18]

The Code for the Eastern Churches

The law of the Eastern-rite Churches in full communion with the Roman papacy was in much the same state as that of the Latin or Western Church before 1917; much more diversity in legislation existed in the various Eastern Catholic Churches. Each had its own special law, in which custom still played an important part. One major difference in Eastern Europe however, specifically in the Orthodox Christian churches was in regards to divorce. Divorce started to slowly be allowed in specific instances such as adultery being committed, abuse, abandonment, impotence and barrenness being the primary justifications for divorce. Eventually, the church began to allow remarriage to occur (for both spouses) post-divorce.[2] In 1929 Pius XI informed the Eastern Churches of his intention to work out a Code for the whole of the Eastern Church. The publication of these Codes for the Eastern Churches regarding the law of persons was made between 1949 through 1958[19] but finalized nearly 30 years later.[6]

The first Code of Canon Law (1917) was almost exclusively for the Latin Church, with extremely limited application to the Eastern Churches.[20] After the Second Vatican Council, (1962 - 1965), another edition was published specifically for the Roman Rite in 1983. Most recently, 1990, the Vatican produced the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches which became the 1st code of Eastern Catholic Canon Law.[21]

Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, principally through the work of 18th-century Athonite monastic scholar Nicodemus the Hagiorite, has compiled canons and commentaries upon them in a work known as the Pēdálion (Greek: Πηδάλιον, "Rudder"), so named because it is meant to "steer" the Church in her discipline. The dogmatic determinations of the Councils are to be applied rigorously, since they are considered to be essential for the Church's unity and the faithful preservation of the Gospel.[22]

Anglican Communion

In the Church of England, the ecclesiastical courts that formerly decided many matters such as disputes relating to marriage, divorce, wills, and defamation, still have jurisdiction of certain church-related matters (e.g. discipline of clergy, alteration of church property, and issues related to churchyards). Their separate status dates back to the 12th century when the Normans split them off from the mixed secular/religious county and local courts used by the Saxons. In contrast to the other courts of England the law used in ecclesiastical matters is at least partially a civil law system, not common law, although heavily governed by parliamentary statutes. Since the Reformation, ecclesiastical courts in England have been royal courts. The teaching of canon law at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge was abrogated by Henry VIII; thereafter practitioners in the ecclesiastical courts were trained in civil law, receiving a Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.) degree from Oxford, or a Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) degree from Cambridge. Such lawyers (called "doctors" and "civilians") were centered at "Doctors Commons", a few streets south of St Paul's Cathedral in London, where they monopolized probate, matrimonial, and admiralty cases until their jurisdiction was removed to the common law courts in the mid-19th century.

Other churches in the Anglican Communion around the world (e.g., the Episcopal Church in the United States, and the Anglican Church of Canada) still function under their own private systems of canon law.

Currently, (2004), there are principles of canon law common to the churches within the Anglican Communion; their existence can be factually established; each province or church contributes through its own legal system to the principles of canon law common within the Communion; these principles have a strong persuasive authority and are fundamental to the self-understanding of each of the churches of the Communion; these principles have a living force, and contain in themselves the possibility of further development; and the existence of these principles both demonstrates unity and promotes unity within the Anglican Communion. [23]

Presbyterian and Reformed churches

In Presbyterian and Reformed churches, canon law is known as "practice and procedure" or "church order", and includes the church's laws respecting its government, discipline, legal practice and worship.

Roman canon law had been criticized by the Presbyterians as early as 1572 in the Admonition to Parliament. The protest centered on the standard defense that canon law could be retained so long as it did not contradict the civil law. According to Polly Ha, the Reformed Church Government refuted this claiming that the bishops had been enforcing canon law for 1500 years.[24]

Lutheranism

The Book of Concord is the historic doctrinal statement of the Lutheran Church, consisting of ten credal documents recognized as authoritative in Lutheranism since the 16th century.[25] However, the Book of Concord is a confessional document (stating orthodox belief) rather than a book of ecclesiastical rules or discipline, like canon law. Each Lutheran national church establishes its own system of church order and discipline, though these are referred to as "canons."

United Methodist Church

The Book of Discipline contains the laws, rules, policies and guidelines for The United Methodist Church. Its last edition was published in 2016.

See also

Abrogation of Old Covenant laws

Akribeia

Canon law (Church of England)

Canon law (Episcopal Church in the United States)

Collections of ancient canons

Decretum Gratiani

Doctor of both laws

Economy (religion)

Fetha Nagast

Ius remonstrandi

List of canon lawyers

Religious law

Rule according to higher law

State religion