CERN

CERN

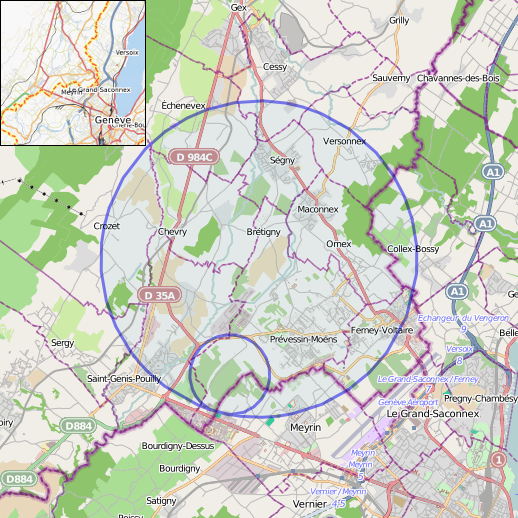

CERN's main site, from Switzerland looking towards France | |

Member states | |

| Formation | September 29, 1954 (1954-09-29)[6] |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Meyrin, Canton of Geneva, Switzerland |

Membership | 23 countries

|

Official languages | English and French |

Council President | Ursula Bassler[7] |

Director General | Fabiola Gianotti |

| Website | home.cern [91] |

| |

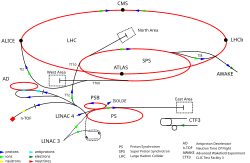

| List of current particle accelerators at CERN | |

| Linac 2 | Accelerates protons |

| Linac 3 | Accelerates ions |

| Linac 4 | Accelerates negative hydrogen ions |

| AD | Decelerates antiprotons |

| LHC | Collides protons or heavy ions |

| LEIR | Accelerates ions |

| PSB | Accelerates protons or ions |

| PS | Accelerates protons or ions |

| SPS | Accelerates protons or ions |

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (French: Organisation européenne pour la recherche nucléaire), known as CERN (/sɜːrn/; French pronunciation: [sɛʁn]; derived from the name Conseil européen pour la recherche nucléaire), is a European research organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, the organization is based in a northwest suburb of Geneva on the Franco–Swiss border and has 23 member states.[8] Israel is the only non-European country granted full membership.[9] CERN is an official United Nations Observer.[10]

The acronym CERN is also used to refer to the laboratory, which in 2016 had 2,500 scientific, technical, and administrative staff members, and hosted about 12,000 users. In the same year, CERN generated 49 petabytes of data.[11]

CERN's main function is to provide the particle accelerators and other infrastructure needed for high-energy physics research – as a result, numerous experiments have been constructed at CERN through international collaborations. The main site at Meyrin hosts a large computing facility, which is primarily used to store and analyse data from experiments, as well as simulate events. Researchers need remote access to these facilities, so the lab has historically been a major wide area network hub. CERN is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web.[12][13]

CERN's main site, from Switzerland looking towards France | |

Member states | |

| Formation | September 29, 1954 (1954-09-29)[6] |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Meyrin, Canton of Geneva, Switzerland |

Membership | 23 countries

|

Official languages | English and French |

Council President | Ursula Bassler[7] |

Director General | Fabiola Gianotti |

| Website | home.cern [91] |

| |

| List of current particle accelerators at CERN | |

| Linac 2 | Accelerates protons |

| Linac 3 | Accelerates ions |

| Linac 4 | Accelerates negative hydrogen ions |

| AD | Decelerates antiprotons |

| LHC | Collides protons or heavy ions |

| LEIR | Accelerates ions |

| PSB | Accelerates protons or ions |

| PS | Accelerates protons or ions |

| SPS | Accelerates protons or ions |

History

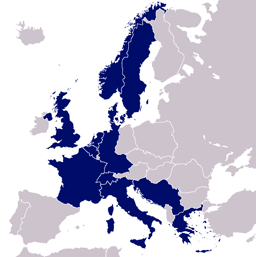

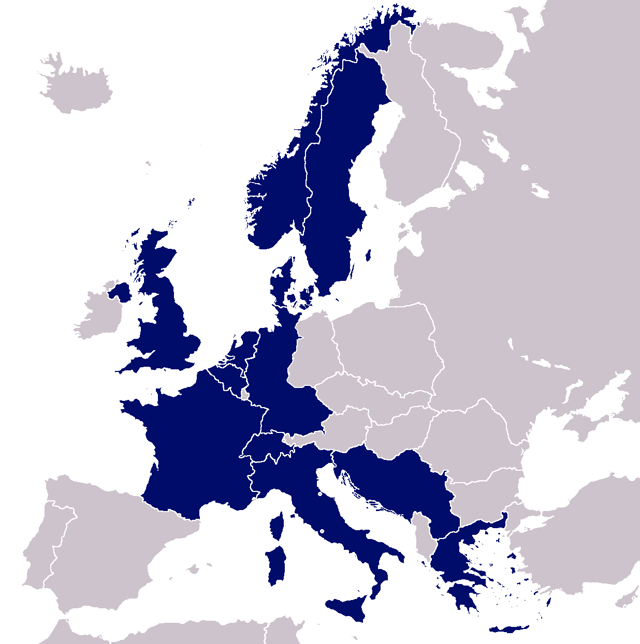

The 12 founding member states of CERN in 1954[6]

The convention establishing CERN was ratified on 29 September 1954 by 12 countries in Western Europe.[6] The acronym CERN originally represented the French words for Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (European Council for Nuclear Research), which was a provisional council for building the laboratory, established by 12 European governments in 1952. The acronym was retained for the new laboratory after the provisional council was dissolved, even though the name changed to the current Organisation Européenne pour la Recherche Nucléaire (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in 1954.[14] According to Lew Kowarski, a former director of CERN, when the name was changed, the abbreviation could have become the awkward OERN, and Werner Heisenberg said that this could "still be CERN even if the name is [not]".

CERN's first president was Sir Benjamin Lockspeiser. Edoardo Amaldi was the general secretary of CERN at its early stages when operations were still provisional, while the first Director-General (1954) was Felix Bloch.[15]

The laboratory was originally devoted to the study of atomic nuclei, but was soon applied to higher-energy physics, concerned mainly with the study of interactions between subatomic particles. Therefore, the laboratory operated by CERN is commonly referred to as the European laboratory for particle physics (Laboratoire européen pour la physique des particules), which better describes the research being performed there.

Founding members

At the sixth session of the CERN Council, which took place in Paris from 29 June - 1 July 1953, the convention establishing the organization was signed, subject to ratification, by 12 states. The convention was gradually ratified by the 12 founding Member States: Belgium, Denmark, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia.[16]

Scientific achievements

Several important achievements in particle physics have been made through experiments at CERN. They include:

1973: The discovery of neutral currents in the Gargamelle bubble chamber;[17]

1983: The discovery of W and Z bosons in the UA1 and UA2 experiments;[18]

1989: The determination of the number of light neutrino families at the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP) operating on the Z boson peak;

1995: The first creation of antihydrogen atoms in the PS210 experiment;[19]

1999: The discovery of direct CP violation in the NA48 experiment;[20]

2010: The isolation of 38 atoms of antihydrogen;[21]

2011: Maintaining antihydrogen for over 15 minutes;[22]

2012: A boson with mass around 125 GeV/c2 consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson.[23]

The 1984 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer for the developments that resulted in the discoveries of the W and Z bosons. The 1992 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to CERN staff researcher Georges Charpak "for his invention and development of particle detectors, in particular the multiwire proportional chamber". The 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to François Englert and Peter Higgs for the theoretical description of the Higgs mechanism in the year after the Higgs boson was found by CERN experiments.

Computer science

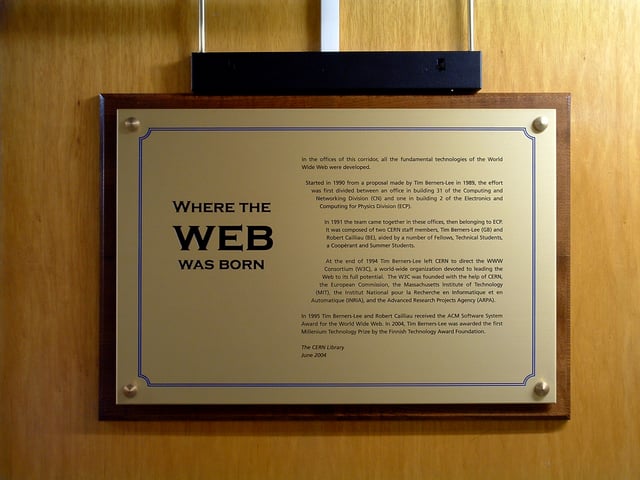

A plaque at CERN commemorating the invention of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau

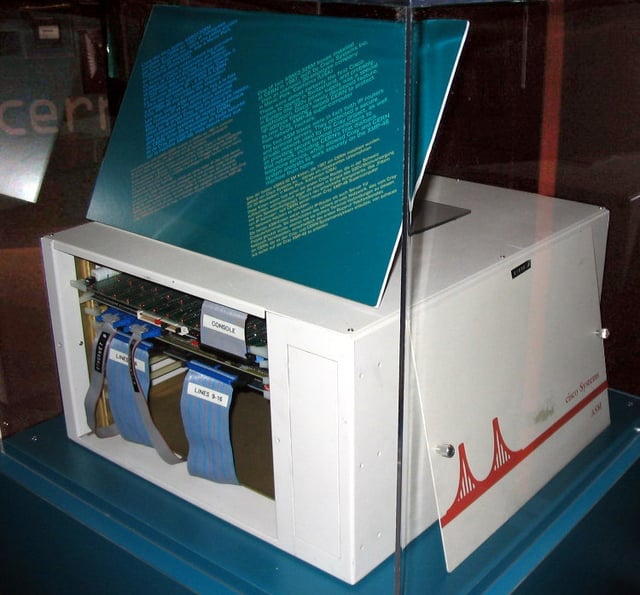

This Cisco Systems router at CERN was one of the first IP routers deployed in Europe.

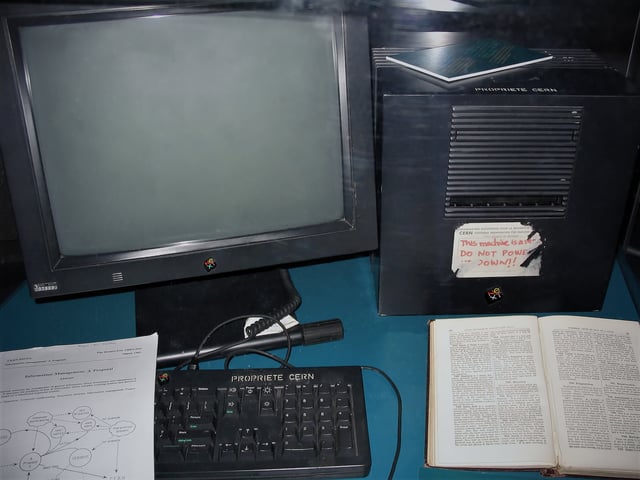

This NeXT Computer used by British scientist Sir Tim Berners-Lee at CERN became the first Web server.

The World Wide Web began as a CERN project named ENQUIRE, initiated by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989 and Robert Cailliau in 1990.[26] Berners-Lee and Cailliau were jointly honoured by the Association for Computing Machinery in 1995 for their contributions to the development of the World Wide Web.

Based on the concept of hypertext, the project was intended to facilitate the sharing of information between researchers. The first website was activated in 1991. On 30 April 1993, CERN announced that the World Wide Web would be free to anyone. A copy[27] of the original first webpage [92] , created by Berners-Lee, is still published on the World Wide Web Consortium's website as a historical document.

Prior to the Web's development, CERN had pioneered the introduction of Internet technology, beginning in the early 1980s.[28]

More recently, CERN has become a facility for the development of grid computing, hosting projects including the Enabling Grids for E-sciencE (EGEE) and LHC Computing Grid. It also hosts the CERN Internet Exchange Point (CIXP), one of the two main internet exchange points in Switzerland.

Particle accelerators

Current complex

Map of the Large Hadron Collider together with the Super Proton Synchrotron at CERN

CERN operates a network of six accelerators and a decelerator. Each machine in the chain increases the energy of particle beams before delivering them to experiments or to the next more powerful accelerator. Currently active machines are:

Two linear accelerators generate low energy particles. LINAC 2 accelerates protons to 50 MeV for injection into the Proton Synchrotron Booster (PSB), and LINAC 3 provides heavy ions at 4.2 MeV/u for injection into the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR).[29]

The Proton Synchrotron Booster increases the energy of particles generated by the proton linear accelerator before they are transferred to the other accelerators.

The Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR) accelerates the ions from the ion linear accelerator, before transferring them to the Proton Synchrotron (PS). This accelerator was commissioned in 2005, after having been reconfigured from the previous Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR).

The 28 GeV Proton Synchrotron (PS), built during 1954—1959 and still operating as a feeder to the more powerful SPS.

The Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), a circular accelerator with a diameter of 2 kilometres built in a tunnel, which started operation in 1976. It was designed to deliver an energy of 300 GeV and was gradually upgraded to 450 GeV. As well as having its own beamlines for fixed-target experiments (currently COMPASS and NA62), it has been operated as a proton–antiproton collider (the SppS collider), and for accelerating high energy electrons and positrons which were injected into the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP). Since 2008, it has been used to inject protons and heavy ions into the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

The On-Line Isotope Mass Separator (ISOLDE), which is used to study unstable nuclei. The radioactive ions are produced by the impact of protons at an energy of 1.0–1.4 GeV from the Proton Synchrotron Booster. It was first commissioned in 1967 and was rebuilt with major upgrades in 1974 and 1992.

The Antiproton Decelerator (AD), which reduces the velocity of antiprotons to about 10% of the speed of light for research of antimatter.

The Compact Linear Collider Test Facility, which studies feasibility for the future normal conducting linear collider project.

The AWAKE experiment, which is a proof-of-principle plasma wakefield accelerator.

Large Hadron Collider

Construction of the CMS detector for LHC at CERN

Many activities at CERN currently involve operating the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and the experiments for it. The LHC represents a large-scale, worldwide scientific cooperation project.

The LHC tunnel is located 100 metres underground, in the region between the Geneva International Airport and the nearby Jura mountains. The majority of its length is on the French side of the border. It uses the 27 km circumference circular tunnel previously occupied by the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP), which was shut down in November 2000. CERN's existing PS/SPS accelerator complexes are used to pre-accelerate protons and lead ions which are then injected into the LHC.

Seven experiments (CMS, ATLAS, LHCb, MoEDAL,[30] TOTEM, LHC-forward and ALICE) are located along the collider; each of them studies particle collisions from a different aspect, and with different technologies. Construction for these experiments required an extraordinary engineering effort. For example, a special crane was rented from Belgium to lower pieces of the CMS detector into its underground cavern, since each piece weighed nearly 2,000 tons. The first of the approximately 5,000 magnets necessary for construction was lowered down a special shaft at 13:00 GMT on 7 March 2005.

The LHC has begun to generate vast quantities of data, which CERN streams to laboratories around the world for distributed processing (making use of a specialized grid infrastructure, the LHC Computing Grid). During April 2005, a trial successfully streamed 600 MB/s to seven different sites across the world.

The LHC resumed operation on 20 November 2009 by successfully circulating two beams, each with an energy of 3.5 teraelectronvolts (TeV). The challenge for the engineers was then to try to line up the two beams so that they smashed into each other. This is like "firing two needles across the Atlantic and getting them to hit each other" according to Steve Myers, director for accelerators and technology.

On 30 March 2010, the LHC successfully collided two proton beams with 3.5 TeV of energy per proton, resulting in a 7 TeV collision energy. However, this was just the start of what was needed for the expected discovery of the Higgs boson. When the 7 TeV experimental period ended, the LHC revved to 8 TeV (4 TeV per proton) starting March 2012, and soon began particle collisions at that energy. In July 2012, CERN scientists announced the discovery of a new sub-atomic particle that was later confirmed to be the Higgs boson.[33] In March 2013, CERN announced that the measurements performed on the newly found particle allowed it to conclude that this is a Higgs boson.[34] In early 2013, the LHC was deactivated for a two-year maintenance period, to strengthen the electrical connections between magnets inside the accelerator and for other upgrades.

On 5 April 2015, after two years of maintenance and consolidation, the LHC restarted for a second run. The first ramp to the record-breaking energy of 6.5 TeV was performed on 10 April 2015.[35][36] In 2016, the design collision rate was exceeded for the first time.[37] A second two-year period of shutdown is scheduled to begin at the end of 2018.

Decommissioned accelerators

The original linear accelerator (LINAC 1).

The 600 MeV Synchrocyclotron (SC) which started operation in 1957 and was shut down in 1991.

The Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), an early collider built from 1966 to 1971 and operated until 1984.

The Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP), which operated from 1989 to 2000 and was the largest machine of its kind, housed in a 27 km-long circular tunnel which now houses the Large Hadron Collider.

The Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR), commissioned in 1982, which assembled the first pieces of true antimatter, in 1995, consisting of nine atoms of antihydrogen. It was closed in 1996, and superseded by the Antiproton Decelerator.

Possible future accelerators

CERN, in collaboration with groups worldwide, is investigating two main concepts for future accelerators: A linear electron-positron collider with a new acceleration concept to increase the energy (CLIC) and a larger version of the LHC, a project currently named Future Circular Collider.[38]

Sites

Interior of office building 40 at the Meyrin site. Building 40 hosts many offices for scientists from the CMS and ATLAS collaborations.

The smaller accelerators are on the main Meyrin site (also known as the West Area), which was originally built in Switzerland alongside the French border, but has been extended to span the border since 1965. The French side is under Swiss jurisdiction and there is no obvious border within the site, apart from a line of marker stones.

The SPS and LEP/LHC tunnels are almost entirely outside the main site, and are mostly buried under French farmland and invisible from the surface. However, they have surface sites at various points around them, either as the location of buildings associated with experiments or other facilities needed to operate the colliders such as cryogenic plants and access shafts. The experiments are located at the same underground level as the tunnels at these sites.

Three of these experimental sites are in France, with ATLAS in Switzerland, although some of the ancillary cryogenic and access sites are in Switzerland. The largest of the experimental sites is the Prévessin site, also known as the North Area, which is the target station for non-collider experiments on the SPS accelerator. Other sites are the ones which were used for the UA1, UA2 and the LEP experiments (the latter are used by LHC experiments).

Outside of the LEP and LHC experiments, most are officially named and numbered after the site where they were located. For example, NA32 was an experiment looking at the production of so-called "charmed" particles and located at the Prévessin (North Area) site while WA22 used the Big European Bubble Chamber (BEBC) at the Meyrin (West Area) site to examine neutrino interactions. The UA1 and UA2 experiments were considered to be in the Underground Area, i.e. situated underground at sites on the SPS accelerator.

Most of the roads on the CERN Meyrin and Prévessin sites are named after famous physicists, such as Richard Feynman, Niels Bohr, and Albert Einstein.

Participation and funding

Member states and budget

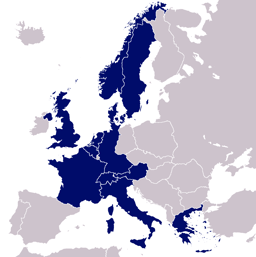

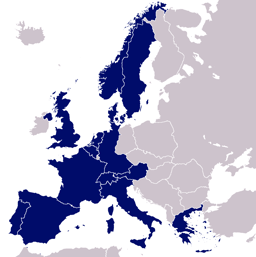

Since its foundation by 12 members in 1954, CERN regularly accepted new members. All new members have remained in the organization continuously since their accession, except Spain and Yugoslavia. Spain first joined CERN in 1961, withdrew in 1969, and rejoined in 1983. Yugoslavia was a founding member of CERN but quit in 1961. Of the 23 members, Israel joined CERN as a full member on 6 January 2014,[39] becoming the first (and currently only) non-European full member.[40]

The budget contributions of member states are computed based on their GDP.[41]

| Member state | Status since | Contribution (million CHF for 2019) | Contribution (fraction of total for 2019) | Contribution per capita[1] (CHF/person for 2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founding Members[2] | ||||

| 29 September 1954 | 30.7 | 2.68% | 2.7 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 20.5 | 1.79% | 3.4 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 160.3 | 14.0% | 2.6 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 236.0 | 20.6% | 2.8 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 12.5 | 1.09% | 1.6 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 118.4 | 10.4% | 2.1 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 51.8 | 4.53% | 3.0 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 28.3 | 2.48% | 5.4 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 30.5 | 2.66% | 3.0 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 47.1 | 4.12% | 4.9 | |

| 29 September 1954 | 184.0 | 16.1% | 2.4 | |

| 0 | 0% | 0.0 | ||

| Acceded Members[4] | ||||

| 1 June 1959 | 24.7 | 2.16% | 2.9 | |

| 1 January 1983[45][47] | 80.7 | 7.06% | 2.0 | |

| 1 January 1986 | 12.5 | 1.09% | 1.3 | |

| 1 January 1991 | 15.1 | 1.32% | 2.8 | |

| 1 July 1991 | 31.9 | 2.79% | 0.8 | |

| 1 July 1992 | 7.0 | 0.609% | 0.7 | |

| 1 July 1993 | 10.9 | 0.950% | 1.1 | |

| 1 July 1993 | 5.6 | 0.490% | 1.0 | |

| 11 June 1999 | 3.4 | 0.297% | 0.4 | |

| 6 January 2014[39] | 19.7 | 1.73% | 2.7 | |

| 17 July 2016[48] | 12.0 | 1.05% | 0.6 | |

| 24 March 2019[49] | 2.5 | 0.221% | 0.1 | |

| Associate Members in the pre-stage to membership | ||||

| 1 April 2016[50] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| 4 July 2017[51][52] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Associate Members | ||||

| 6 May 2015[53] | 5.7 | N/A | N/A | |

| 31 July 2015[54] | 1.7 | N/A | N/A | |

| 5 Oct 2016[55] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| 16 Jan 2017[56] | 13.8 | N/A | N/A | |

| 8 Jan 2018[57] | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Total Members, Candidates and Associates | **1,146.0**[41] | **100.0%** | N/A | |

| Maps of the history of CERN membership |

|---|

Enlargement

Associate Members, Candidates:

Turkey signed an association agreement on 12 May 2014[58] and became an associate member on 6 May 2015.

Pakistan signed an association agreement on 19 December 2014[59] and became an associate member on 31 July 2015.[60][61]

Cyprus signed an association agreement on 5 October 2012 and became an associate Member in the pre-stage to membership on 1 April 2016.[50]

Ukraine signed an association agreement on 3 October 2013. The agreement was ratified on 5 October 2016.[55]

India signed an association agreement on 21 November 2016.[62] The agreement was ratified on 16 January 2017.[56]

Slovenia was approved for admission as an Associate Member state in the pre-stage to membership on 16 December 2016.[51] The agreement was ratified on 4 July 2017.[52]

Lithuania was approved for admission as an Associate Member state on 16 June 2017. The association agreement was signed on 27 June 2017 and ratified on 8 January 2018.[63][57]

Croatia was approved for admission as an Associate Member state on 28 February 2019.[64]

International relations

Three countries have observer status:[65]

Japan – since 1995

Russia – since 1993

United States – since 1997

Also observers are the following international organizations:

UNESCO – since 1954

Europe European Commission – since 1985

JINR - since 2014

Non-Member States (with dates of Co-operation Agreements) currently involved in CERN programmes are:[66]

Albania

Algeria

Argentina – 11 March 1992

Armenia – 25 March 1994

Australia – 1 November 1991

Azerbaijan – 3 December 1997

Bangladesh

Belarus – 28 June 1994

Bolivia

Brazil – 19 February 1990 & October 2006

Canada – 11 October 1996

Chile – 10 October 1991

China – 12 July 1991, 14 August 1997 & 17 February 2004

Colombia – 15 May 1993

Croatia – 18 July 1991

Ecuador

Egypt – 16 January 2006

Estonia – 23 April 1996

Georgia – 11 October 1996

Iceland – 11 September 1996

Iran – 5 July 2001

Jordan - 12 June 2003.[67] MoU with Jordan and SESAME, in preparation of a cooperation agreement signed in 2004.[68]

Lithuania – 9 November 2004

North Macedonia – 27 April 2009

Mexico – 20 February 1998

Mongolia

Montenegro – 12 October 1990

Morocco – 14 April 1997

New Zealand – 4 December 2003

Peru – 23 February 1993

Saudi Arabia – 21 January 2006

South Africa – 4 July 1992

South Korea – 25 October 2006

United Arab Emirates – 18 January 2006

Vietnam

CERN also has scientific contacts with the following countries:[66]

Cuba

Ghana

Ireland

Latvia

Lebanon

Madagascar

Malaysia

Mozambique

Palestine

Philippines

Qatar

Rwanda

Singapore

Sri Lanka

Taiwan

Thailand

Tunisia

Uzbekistan

International research institutions, such as CERN, can aid in science diplomacy.[71]

Associated institutions

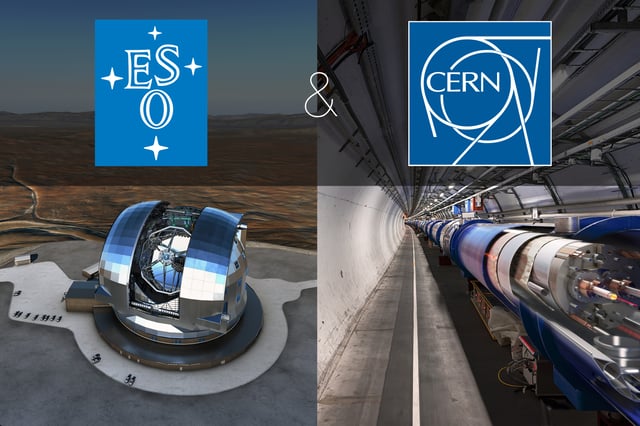

ESO and CERN have a cooperation agreement.[72]

European Southern Observatory

Swiss National Supercomputing Centre

Open access publishing

CERN has initiated an open access publishing project to convert scientific articles in high energy physics into gold open access by redirecting subscription fees. In the first phase from 2014-2016 3,000 libraries, consortia, research organisations, publishers and funding agencies in various countries participated.[73] All publications by CERN authors are published with gold open access.[74]

Public exhibits

The Globe of Science and Innovation at CERN

Facilities at CERN open to the public include:

The Globe of Science and Innovation, which opened in late 2005 and is used four times a week for special exhibits.

The Microcosm museum on particle physics and CERN history.

CERN also provides daily tours to certain facilities such as the Synchro-cyclotron (CERNs first particle accelerator) and the superconducting magnet workshop.

In popular culture

The statue of Shiva engaging in the Nataraja dance presented by the Department of Atomic Energy of India.

Line 18 goes to CERN

The band Les Horribles Cernettes was founded by women from CERN. The name was chosen so to have the same initials as the LHC.[75][76]

CERN's Large Hadron Collider is the subject of a (scientifically accurate) rap video starring Katherine McAlpine with some of the facility's staff.[77][78]

Particle Fever, a 2013 documentary, explores CERN throughout the inside and depicts the events surrounding the 2012 discovery of the Higgs Boson

CERN is depicted in an episode of South Park (Season 13, Episode 6) called "Pinewood Derby". Randy Marsh, the father of one of the main characters, breaks into the "Hadron Particle Super Collider in Switzerland" and steals a "superconducting bending magnet created for use in tests with particle acceleration" to use in his son Stan's Pinewood Derby racer. Randy breaks into CERN dressed in disguise as Princess Leia from the Star Wars saga. The break-in is captured on surveillance tape which is then broadcast on the news.[79]

John Titor, a self-proclaimed time traveler, alleged that CERN would invent time travel in 2001.

CERN is depicted in the visual novel/anime series Steins;Gate as SERN, a shadowy organization that has been researching time travel in order to restructure and control the world.

In Dan Brown's mystery-thriller novel Angels & Demons and film of the same name, a canister of antimatter is stolen from CERN.[80]

In the popular children's series The 39 Clues, CERN is said to be an Ekaterina stronghold hiding the clue hydrogen.

In Robert J. Sawyer's science fiction novel Flashforward, at CERN, the Large Hadron Collider accelerator is performing a run to search for the Higgs boson when the entire human race sees themselves twenty-one years and six months in the future.

In season 3 episode 15 of the TV sitcom The Big Bang Theory titled "The Large Hadron Collision", Leonard and Raj travel to CERN to attend a conference and see the LHC.

The 2012 student film Decay, which centers on the idea of the Large Hadron Collider transforming people into zombies, was filmed on location in CERN's maintenance tunnels.[81]

The Compact Muon Solenoid at CERN was used as the basis for the Megadeth's Super Collider album cover.

In Super Lovers, Haruko (Ren's mother) worked at CERN, and Ren was taught by CERN professors

CERN forms part of the back story of the massively multiplayer augmented reality game Ingress.[82] CERN forms also part of the story of the Japanese anime television series Ingress: The Animation in 2019, based on Niantic's augmented reality mobile game of the same name.

In season 10 episode 6 of the BBC TV show Doctor Who titled "Extremis", CERN and its physicists are involved in a mysterious plot involving a book that causes everyone who reads it to kill themselves.

In 2015, Sarah Charley, US communications manager for LHC experiments at CERN with graduate students Jesse Heilman of the University of California, Riverside, and Tom Perry and Laser Seymour Kaplan of the University of Wisconsin, Madison created a parody video [98] of “Collide” a song by American artist Howie Day.[83] The lyrics were changed to be from the perspective of a proton in the Large Hadron Collider. After seeing the parody, Day re-recorded the song with the new lyrics and in February, 2017 Day released this new version of "Collide" in a video [99] created during his visit to CERN.[84]

See also

Joint Institute for Nuclear Research

CERN Openlab

Fermilab

Large Hadron Collider – Wikipedia book

Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek

Science and Technology Facilities council

Science and technology in Switzerland

Scientific Linux

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory