Burn

Burn

| Burn | |

|---|---|

| Second-degree burn of the hand | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Superficial: Red without blisters[1]Partial-thickness: Blisters and pain[1]Full-thickness: Area stiff and not painful[1] |

| Complications | Infection[2] |

| Duration | Days to weeks[1] |

| Types | Superficial, partial-thickness, full-thickness[1] |

| Causes | Heat,cold,electricity,chemicals,friction,radiation[3] |

| Risk factors | Open cooking fires, unsafecook stoves, smoking,alcoholism, dangerous work environment[4] |

| Treatment | Depends on the severity[1] |

| Medication | Pain medication,intravenous fluids,tetanus toxoid[1] |

| Frequency | 67 million (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 176,000 (2015)[6] |

A burn is a type of injury to skin, or other tissues, caused by heat, cold, electricity, chemicals, friction, or radiation.[3] Most burns are due to heat from hot liquids, solids, or fire.[7] While rates are similar for males and females the underlying causes often differ.[4] Among women in some areas, risk is related to use of open cooking fires or unsafe cook stoves.[4] Among men, risk is related to the work environments.[4] Alcoholism and smoking are other risk factors.[4] Burns can also occur as a result of self-harm or violence between people.[4]

Burns that affect only the superficial skin layers are known as superficial or first-degree burns.[1][8] They appear red without blisters and pain typically lasts around three days.[1][8] When the injury extends into some of the underlying skin layer, it is a partial-thickness or second-degree burn.[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*listers are frequently present and they are often very painful.scarring[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*n a full-thickness or third-degree burn, the injury extends to all layers of the skin.[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*ealing typically does not occur on its own.muscle tendons bone[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*he burn is often black and frequently leads to loss of the burned part.[9]

Burns are generally preventable.[4] Treatment depends on the severity of the burn.[1] Superficial burns may be managed with little more than simple pain medication, while major burns may require prolonged treatment in specialized burn centers.[1]Emergency%20Medicine%3A]] [8]dressings[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*if large.skin grafting[1]intravenous fluid capillary tissue swelling[8] The most common complications of burns involve infection.[2] Tetanus toxoid should be given if not up to date.[1]

In 2015, fire and heat resulted in 67 million injuries.[5] This resulted in about 2.9 million hospitalizations and 176,000 deaths.[6][10] Most deaths due to burns occur in the developing world, particularly in Southeast Asia.[4] While large burns can be fatal, treatments developed since 1960 have improved outcomes, especially in children and young adults.[11] In the United States, approximately 96% of those admitted to a burn center survive their injuries.[12] The long-term outcome is related to the size of burn and the age of the person affected.[1]

| Burn | |

|---|---|

| Second-degree burn of the hand | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Superficial: Red without blisters[1]Partial-thickness: Blisters and pain[1]Full-thickness: Area stiff and not painful[1] |

| Complications | Infection[2] |

| Duration | Days to weeks[1] |

| Types | Superficial, partial-thickness, full-thickness[1] |

| Causes | Heat,cold,electricity,chemicals,friction,radiation[3] |

| Risk factors | Open cooking fires, unsafecook stoves, smoking,alcoholism, dangerous work environment[4] |

| Treatment | Depends on the severity[1] |

| Medication | Pain medication,intravenous fluids,tetanus toxoid[1] |

| Frequency | 67 million (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 176,000 (2015)[6] |

Signs and symptoms

The characteristics of a burn depend upon its depth.

Superficial burns cause pain lasting two or three days, followed by peeling of the skin over the next few days.[8][13] Individuals suffering from more severe burns may indicate discomfort or complain of feeling pressure rather than pain. Full-thickness burns may be entirely insensitive to light touch or puncture.[13] While superficial burns are typically red in color, severe burns may be pink, white or black.[13] Burns around the mouth or singed hair inside the nose may indicate that burns to the airways have occurred, but these findings are not definitive.[14]S]] Itchiness[15][16] l distress.[17]

| Type[1] | Layers involved | Appearance | Texture | Sensation | Healing Time | Prognosis | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial (first-degree) | Epidermis[8] | Redwithout blisters[1] | Dry | Painful[1] | 5–10 days[1][18] | Heals well.[1]Repeatedsunburnsincrease the risk ofskin cancerlater in life.[19] | |

| Superficial partial thickness (second-degree) | Extends into superficial (papillary)dermis[1] | Redness with clearblister.[1][1] | Moist[1] | Very painful[1] | 2–3 weeks[1][13] | Local infection (cellulitis) but no scarring typically[13] | |

| Deep partial thickness (second-degree) | Extends into deep (reticular) dermis[1] | Yellow or white.Less blanching.May be blistering.[1] | Fairly dry[13] | Pressure and discomfort[13] | 3–8 weeks[1] | Scarring,contractures(may require excision andskin grafting)[13] | |

| Full thickness (third-degree) | Extends through entire dermis[1] | Stiff and white/brown.[1]No blanching.[13] | Leathery[1] | Painless[1] | Prolonged (months) and incomplete[1] | Scarring, contractures, amputation (early excision recommended)[13] | |

| Fourth-degree | Extends through entire skin, and into underlying fat, muscle and bone[1] | Black; charred witheschar | Dry | Painless | Requires excision[1] | Amputation, significant functional impairment and in some cases, death.[1] |

Cause

Burns are caused by a variety of external sources classified as thermal (heat-related), chemical, electrical, and radiation.[20] In the United States, the most common causes of burns are: fire or flame (44%), scalds (33%), hot objects (9%), electricity (4%), and chemicals (3%).[21] Most (69%) burn injuries occur at home or at work (9%),[12] and most are accidental, with 2% due to assault by another, and 1–2% resulting from a suicide attempt.[17] These sources can cause inhalation injury to the airway and/or lungs, occurring in about 6%.[2]

Burn injuries occur more commonly among the poor.[17] Smoking and alcoholism are other risk factor.[7] Fire-related burns are generally more common in colder climates.[17] Specific risk factors in the developing world include cooking with open fires or on the floor[3] as well as developmental disabilities in children and chronic diseases in adults.[22]

Thermal

In the United States, fire and hot liquids are the most common causes of burns.[2] Of house fires that result in death, smoking causes 25% and heating devices cause 22%.[3] Almost half of injuries are due to efforts to fight a fire.[3] Scalding is caused by hot liquids or gases and most commonly occurs from exposure to hot drinks, high temperature tap water in baths or showers, hot cooking oil, or steam.[23] Scald injuries are most common in children under the age of five[1] and, in the United States and Australia, this population makes up about two-thirds of all burns.[2] Contact with hot objects is the cause of about 20–30% of burns in children.[2] Generally, scalds are first- or second-degree burns, but third-degree burns may also result, especially with prolonged contact.[24] Fireworks are a common cause of burns during holiday seasons in many countries.[25] This is a particular risk for adolescent males.[26]

Chemical

Chemicals cause from 2 to 11% of all burns and contribute to as many as 30% of burn-related deaths.[27] Chemical burns can be caused by over 25,000 substances,[1] most of which are either a strong base (55%) or a strong acid (26%).[27] Most chemical burn deaths are secondary to ingestion.[1] Common agents include: sulfuric acid as found in toilet cleaners, sodium hypochlorite as found in bleach, and halogenated hydrocarbons as found in paint remover, among others.[1] Hydrofluoric acid can cause particularly deep burns that may not become symptomatic until some time after exposure.[28] Formic acid may cause the breakdown of significant numbers of red blood cells.[14]

Electrical

Electrical burns or injuries are classified as high voltage (greater than or equal to 1000 volts), low voltage (less than 1000 volts), or as flash burns secondary to an electric arc.[1] The most common causes of electrical burns in children are electrical cords (60%) followed by electrical outlets (14%).[2] Lightning may also result in electrical burns.[29] Risk factors for being struck include involvement in outdoor activities such as mountain climbing, golf and field sports, and working outside.[16] Mortality from a lightning strike is about 10%.[16]

While electrical injuries primarily result in burns, they may also cause fractures or dislocations secondary to blunt force trauma or muscle contractions.[16] In high voltage injuries, most damage may occur internally and thus the extent of the injury cannot be judged by examination of the skin alone.[16] Contact with either low voltage or high voltage may produce cardiac arrhythmias or cardiac arrest.[16]

Radiation

Radiation burns may be caused by protracted exposure to ultraviolet light (such as from the sun, tanning booths or arc welding) or from ionizing radiation (such as from radiation therapy, X-rays or radioactive fallout).[30] Sun exposure is the most common cause of radiation burns and the most common cause of superficial burns overall.[31] There is significant variation in how easily people sunburn based on their skin type.[32] Skin effects from ionizing radiation depend on the amount of exposure to the area, with hair loss seen after 3 Gy, redness seen after 10 Gy, wet skin peeling after 20 Gy, and necrosis after 30 Gy.[33] Redness, if it occurs, may not appear until some time after exposure.[33] Radiation burns are treated the same as other burns.[33] Microwave burns occur via thermal heating caused by the microwaves.[34] While exposures as short as two seconds may cause injury, overall this is an uncommon occurrence.[34]

Non-accidental

In those hospitalized from scalds or fire burns, 3–10% are from assault.[35] Reasons include: child abuse, personal disputes, spousal abuse, elder abuse, and business disputes.[35] An immersion injury or immersion scald may indicate child abuse.[24] It is created when an extremity, or sometimes the buttocks are held under the surface of hot water.[24] It typically produces a sharp upper border and is often symmetrical,[24] known as "sock burns", "glove burns", or "zebra stripes" - where folds have prevented certain areas from burning.[36] Deliberate cigarette burns are preferentially found on the face, or the back of the hands and feet.[36] Other high-risk signs of potential abuse include: circumferential burns, the absence of splash marks, a burn of uniform depth, and association with other signs of neglect or abuse.[37]

Bride burning, a form of domestic violence, occurs in some cultures, such as India where women have been burned in revenge for what the husband or his family consider an inadequate dowry.[38][39] In Pakistan, acid burns represent 13% of intentional burns, and are frequently related to domestic violence.[37] Self-immolation (setting oneself on fire) is also used as a form of protest in various parts of the world.[17]

Pathophysiology

Three degrees of burns

At temperatures greater than 44 °C (111 °F), proteins begin losing their three-dimensional shape and start breaking down.[40]*R]]*his results in cell and tissue damage. tioning of the skin.[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*hey include disruption of the skin's sensation, ability to prevent water loss through evaporation, and ability to control body temperature.

In large burns (over 30% of the total body surface area), there is a significant inflammatory response.[41] This results in increased leakage of fluid from the capillaries,[14]S]] plasma[CITE|1|https://openlibrary.org/search?q=Tintinalli%2C%20Judith%20E.%20%282010%29.%20*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]organs gastrointestinal tract sult in renal failure and stomach ulcers.[42]

Increased levels of catecholamines and cortisol can cause a hypermetabolic state that can last for years.[41] This is associated with increased cardiac output, metabolism, a fast heart rate, and poor immune function.[41]

Diagnosis

Burns can be classified by depth, mechanism of injury, extent, and associated injuries.

The most commonly used classification is based on the depth of injury.

The depth of a burn is usually determined via examination, although a biopsy may also be used.[1]*Emergency%20Medicine%3A]]*t may be difficult to accurately determine the depth of a burn on a single examination and repeated examinations over a few days may be necessary.headache carbon monoxide poisoning[43]Cyanide poisoning[14]

Size

Burn severity is determined through, among other things, the size of the skin affected.

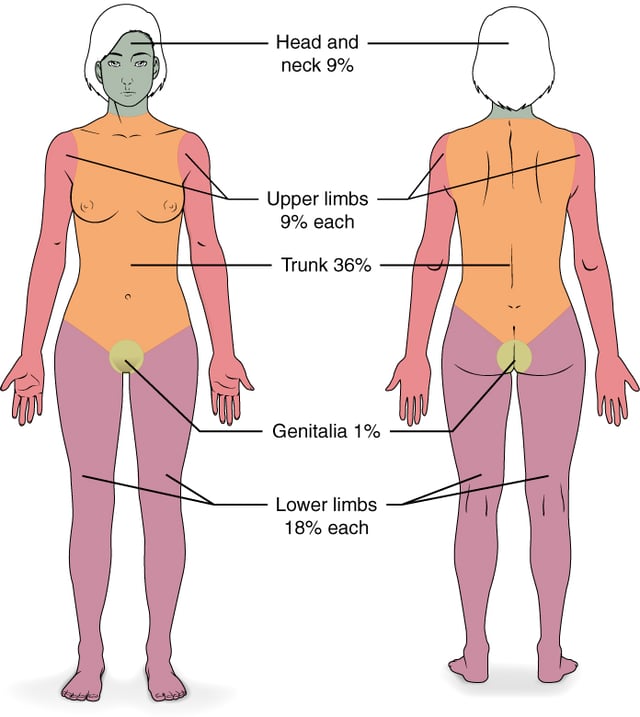

There are a number of methods to determine the TBSA, including the Wallace rule of nines, Lund and Browder chart, and estimations based on a person's palm size.[8] The rule of nines is easy to remember but only accurate in people over 16 years of age.[8] More accurate estimates can be made using Lund and Browder charts, which take into account the different proportions of body parts in adults and children.[8] The size of a person's handprint (including the palm and fingers) is approximately 1% of their TBSA.[8]

Severity

| Minor | Moderate | Major |

|---|---|---|

| Adult <10% TBSA | Adult 10–20% TBSA | Adult >20% TBSA |

| Young or old < 5% TBSA | Young or old 5–10% TBSA | Young or old >10% TBSA |

| <2% full thickness burn | 2–5% full thickness burn | 5% full thickness burn |

| High voltage injury | High voltage burn | |

| Possible inhalation injury | Known inhalation injury | |

| Circumferential burn | Significant burn to face, joints, hands or feet | |

| Other health problems | Associated injuries |

To determine the need for referral to a specialized burn unit, the American Burn Association devised a classification system.

Under this system, burns can be classified as major, moderate and minor.

This is assessed based on a number of factors, including total body surface area affected, the involvement of specific anatomical zones, the age of the person, and associated injuries.[43] Minor burns can typically be managed at home, moderate burns are often managed in hospital, and major burns are managed by a burn center.[43]

Prevention

Historically, about half of all burns were deemed preventable.[3] Burn prevention programs have significantly decreased rates of serious burns.[40] Preventive measures include: limiting hot water temperatures, smoke alarms, sprinkler systems, proper construction of buildings, and fire-resistant clothing.[3] Experts recommend setting water heaters below 48.8 °C (119.8 °F).[2] Other measures to prevent scalds include using a thermometer to measure bath water temperatures, and splash guards on stoves.[40] While the effect of the regulation of fireworks is unclear, there is tentative evidence of benefit[44] with recommendations including the limitation of the sale of fireworks to children.[2]

Management

Resuscitation begins with the assessment and stabilization of the person's airway, breathing and circulation.[8] If inhalation injury is suspected, early intubation may be required.[14]*S]]*his is followed by care of the burn wound itself. People with extensive burns may be wrapped in clean sheets until they arrive at a hospital. ithin the last five years.[45] In the United States, 95% of burns that present to the emergency department are treated and discharged; 5% require hospital admission.[17] With major burns, early feeding is important.[41] Protein intake should also be increased, and trace elements and vitamins are often required.[46] Hyperbaric oxygenation may be useful in addition to traditional treatments.[47]

Intravenous fluids

In those with poor tissue perfusion, boluses of isotonic crystalloid solution should be given.[8] In children with more than 10–20% TBSA burns, and adults with more than 15% TBSA burns, formal fluid resuscitation and monitoring should follow.[8][48][49] This should be begun pre-hospital if possible in those with burns greater than 25% TBSA.[48] The Parkland formula can help determine the volume of intravenous fluids required over the first 24 hours. The formula is based on the affected individual's TBSA and weight. Half of the fluid is administered over the first 8 hours, and the remainder over the following 16 hours. The time is calculated from when the burn occurred, and not from the time that fluid resuscitation began. Children require additional maintenance fluid that includes glucose.[14] Additionally, those with inhalation injuries require more fluid.[50] While inadequate fluid resuscitation may cause problems, over-resuscitation can also be detrimental.[51] The formulas are only a guide, with infusions ideally tailored to a urinary output of >30 mL/h in adults or >1mL/kg in children and mean arterial pressure greater than 60 mmHg.[14]

While lactated Ringer's solution is often used, there is no evidence that it is superior to normal saline.[8] Crystalloid fluids appear just as good as colloid fluids, and as colloids are more expensive they are not recommended.[52][53] Blood transfusions are rarely required.[1] They are typically only recommended when the hemoglobin level falls below 60-80 g/L (6-8 g/dL)[54] due to the associated risk of complications.[14]S]]

Wound care

Early cooling (within 30 minutes of the burn) reduces burn depth and pain, but care must be taken as over-cooling can result in hypothermia.[1][8] It should be performed with cool water 10–25 °C (50.0–77.0 °F) and not ice water as the latter can cause further injury.[8][40]*R]]*hemical burns may require extensive irrigation.removal of dead tissue d care. If intact blisters are present, it is not clear what should be done with them. Some tentative evidence supports leaving them intact. Second-degree burns should be re-evaluated after two days.[40]

In the management of first and second-degree burns, little quality evidence exists to determine which dressing type to use.[55] It is reasonable to manage first-degree burns without dressings.[40] While topical antibiotics are often recommended, there is little evidence to support their use.[56] Silver sulfadiazine (a type of antibiotic) is not recommended as it potentially prolongs healing time.[55] There is insufficient evidence to support the use of dressings containing silver[58] or negative-pressure wound therapy.[59] Silver sulfadiazine does not appear to differ from silver containing foam dressings with respect to healing.[60]

Medications

Burns can be very painful and a number of different options may be used for pain management. These include simple analgesics (such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen) and opioids such as morphine. Benzodiazepines may be used in addition to analgesics to help with anxiety.[40] During the healing process, antihistamines, massage, or transcutaneous nerve stimulation may be used to aid with itching.[15] Antihistamines, however, are only effective for this purpose in 20% of people.[61] There is tentative evidence supporting the use of gabapentin[15] and its use may be reasonable in those who do not improve with antihistamines.[62] Intravenous lidocaine requires more study before it can be recommended for pain.[63]

Intravenous antibiotics are recommended before surgery for those with extensive burns (>60% TBSA).[64] As of 2008, guidelines do not recommend their general use due to concerns regarding antibiotic resistance[56] and the increased risk of fungal infections.[14] Tentative evidence, however, shows that they may improve survival rates in those with large and severe burns.[56] Erythropoietin has not been found effective to prevent or treat anemia in burn cases.[14] In burns caused by hydrofluoric acid, calcium gluconate is a specific antidote and may be used intravenously and/or topically.[28] Recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) in those with burns that involve more than 40% of their body appears to speed healing without affecting the risk of death.[65] The use of steroids is of unclear evidence.[66]

Surgery

Wounds requiring surgical closure with skin grafts or flaps (typically anything more than a small full thickness burn) should be dealt with as early as possible.[67] Circumferential burns of the limbs or chest may need urgent surgical release of the skin, known as an escharotomy.[68] This is done to treat or prevent problems with distal circulation, or ventilation.[68] It is uncertain if it is useful for neck or digit burns.[68] Fasciotomies may be required for electrical burns.[68]

Skin grafts can involve temporary skin substitute, derived from animal (human donor or pig) skin or synthesized.

They are used to cover the wound as a dressing, preventing infection and fluid loss, but will eventually need to be removed.

Alternatively, human skin can be treated to be left on permanently without rejection.[69]

Alternative medicine

Honey has been used since ancient times to aid wound healing and may be beneficial in first- and second-degree burns.[70] There is tentative evidence that honey helps heal partial thickness burns.[71] The evidence for aloe vera is of poor quality.[72] While it might be beneficial in reducing pain,[18] and a review from 2007 found tentative evidence of improved healing times,[73] a subsequent review from 2012 did not find improved healing over silver sulfadiazine.[72] There were only three randomized controlled trials for the use of plants for burns, two for aloe vera and one for oatmeal.[74]

There is little evidence that vitamin E helps with keloids or scarring.[75] Butter is not recommended.[76] In low income countries, burns are treated up to one-third of the time with traditional medicine, which may include applications of eggs, mud, leaves or cow dung.[22] Surgical management is limited in some cases due to insufficient financial resources and availability.[22] There are a number of other methods that may be used in addition to medications to reduce procedural pain and anxiety including: virtual reality therapy, hypnosis, and behavioral approaches such as distraction techniques.[62]

Prognosis

| TBSA | Mortality |

|---|---|

| 0–9% | 0.6% |

| 10–19% | 2.9% |

| 20–29% | 8.6% |

| 30–39% | 16% |

| 40–49% | 25% |

| 50–59% | 37% |

| 60–69% | 43% |

| 70–79% | 57% |

| 80–89% | 73% |

| 90–100% | 85% |

| Inhalation | 23% |

The prognosis is worse in those with larger burns, those who are older, and those who are females.[1] The presence of a smoke inhalation injury, other significant injuries such as long bone fractures, and serious co-morbidities (e.g. heart disease, diabetes, psychiatric illness, and suicidal intent) also influence prognosis.[1] On average, of those admitted to United States burn centers, 4% die,[2] with the outcome for individuals dependent on the extent of the burn injury. For example, admittees with burn areas less than 10% TBSA had a mortality rate of less than 1%, while admittees with over 90% TBSA had a mortality rate of 85%.[77] In Afghanistan, people with more than 60% TBSA burns rarely survive.[2] The Baux score has historically been used to determine prognosis of major burns. However, with improved care, it is no longer very accurate.[14]*S]]*he score is determined by adding the size of the burn (% TBSA) to the age of the person, and taking that to be more or less equal to the risk of death.years lived with disability disability adjusted life years[10]

Complications

A number of complications may occur, with infections being the most common.[2] In order of frequency, potential complications include: pneumonia, cellulitis, urinary tract infections and respiratory failure.[2] Risk factors for infection include: burns of more than 30% TBSA, full-thickness burns, extremes of age (young or old), or burns involving the legs or perineum.[78] Pneumonia occurs particularly commonly in those with inhalation injuries.[14]

Anemia secondary to full thickness burns of greater than 10% TBSA is common.[8] Electrical burns may lead to compartment syndrome or rhabdomyolysis due to muscle breakdown.[14]S]] [41]Keloids[75] urn, children may have significant psychological trauma and experience post-traumatic stress disorder.[79] Scarring may also result in a disturbance in body image.[79] In the developing world, significant burns may result in social isolation, extreme poverty and child abandonment.[17]

Epidemiology

Disability-adjusted life years for fires per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[80] no data < 50 50–100 100–150 150–200 200–250 250–300 300–350 350–400 400–450 450–500 500–600 > 600

In 2015 fire and heat resulted in 67 million injuries.[5] This resulted in about 2.9 million hospitalizations and 238,000 dying.[10] This is down from 300,000 deaths in 1990.[81] This makes it the fourth leading cause of injuries after motor vehicle collisions, falls, and violence.[17] About 90% of burns occur in the developing world.[17] This has been attributed partly to overcrowding and an unsafe cooking situation.[17] Overall, nearly 60% of fatal burns occur in Southeast Asia with a rate of 11.6 per 100,000.[2] The number of fatal burns has changed from 280,000 in 1990 to 176,000 in 2015.[82][6]

In the developed world, adult males have twice the mortality as females from burns.

This is most probably due to their higher risk occupations and greater risk-taking activities.

In many countries in the developing world, however, females have twice the risk of males.

This is often related to accidents in the kitchen or domestic violence.[17] In children, deaths from burns occur at more than ten times the rate in the developing than the developed world.[17] Overall, in children it is one of the top fifteen leading causes of death.[3] From the 1980s to 2004, many countries have seen both a decrease in the rates of fatal burns and in burns generally.[17]

Developed countries

An estimated 500,000 burn injuries receive medical treatment yearly in the United States.[40]*R]]*hey resulted in about 3,300 deaths in 2008.[3] Most burns (70%) and deaths from burns occur in males.[12] idence of scalds occurs in children less than five years old and adults over 65.[1] Electrical burns result in about 1,000 deaths per year.[83] Lightning results in the death of about 60 people a year.[16] In Europe, intentional burns occur most commonly in middle aged men.[35]

Developing countries

In India, about 700,000 to 800,000 people per year sustain significant burns, though very few are looked after in specialist burn units.[84] The highest rates occur in women 16–35 years of age.[84] Part of this high rate is related to unsafe kitchens and loose-fitting clothing typical to India.[84] It is estimated that one-third of all burns in India are due to clothing catching fire from open flames.[85] Intentional burns are also a common cause and occur at high rates in young women, secondary to domestic violence and self-harm.[17][35]

History

Guillaume Dupuytren (1777–1835) who developed the degree classification of burns

Cave paintings from more than 3,500 years ago document burns and their management.[11] The earliest Egyptian records on treating burns describes dressings prepared with milk from mothers of baby boys,[86] and the 1500 BCE Edwin Smith Papyrus describes treatments using honey and the salve of resin.[11] Many other treatments have been used over the ages, including the use of tea leaves by the Chinese documented to 600 BCE, pig fat and vinegar by Hippocrates documented to 400 BCE, and wine and myrrh by Celsus documented to 100 CE.[11] French barber-surgeon Ambroise Paré was the first to describe different degrees of burns in the 1500s.[87] Guillaume Dupuytren expanded these degrees into six different severities in 1832.[11][88]

The first hospital to treat burns opened in 1843 in London, England and the development of modern burn care began in the late 1800s and early 1900s.[11][87] During World War I, Henry D. Dakin and Alexis Carrel developed standards for the cleaning and disinfecting of burns and wounds using sodium hypochlorite solutions, which significantly reduced mortality.[11] In the 1940s, the importance of early excision and skin grafting was acknowledged, and around the same time, fluid resuscitation and formulas to guide it were developed.[11] In the 1970s, researchers demonstrated the significance of the hypermetabolic state that follows large burns.[11]