Banū Mūsā

Banū Mūsā

Banū Mūsā | |

|---|---|

| Born | 9th century |

| Residence | Baghdad |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Apollonius of Perga, Ptolemy, Galen, Al-Maʾmūn, Mūsā ibn Shākir, Yahya ibn Abi Mansur |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Main interests | Astronomy, geometry |

| Notable works | Book of Ingenious Devices, Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures |

| Notable ideas | Application of arithmetic to geometry[1] |

| Influenced | Thabit ibn Qurra, Hunayn Ibn Ishaq, Ibn al‐Haytham, Naṣīr al‐Dīn al‐Ṭūsī, Gerard of Cremona, Leonardo Fibonacci, Jordanus de Nemore, Roger Bacon[2] |

The Banū Mūsā brothers ("Sons of Moses"), namely Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873), Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century), were three 9th-century Persian[3][4] scholars who lived and worked in Baghdad. They are known for their Book of Ingenious Devices on automata (automatic machines) and mechanical devices. Another important work of theirs is the Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures, a foundational work on geometry that was frequently quoted by both Islamic and European mathematicians.[2]

Banū Mūsā | |

|---|---|

| Born | 9th century |

| Residence | Baghdad |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Apollonius of Perga, Ptolemy, Galen, Al-Maʾmūn, Mūsā ibn Shākir, Yahya ibn Abi Mansur |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Main interests | Astronomy, geometry |

| Notable works | Book of Ingenious Devices, Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures |

| Notable ideas | Application of arithmetic to geometry[1] |

| Influenced | Thabit ibn Qurra, Hunayn Ibn Ishaq, Ibn al‐Haytham, Naṣīr al‐Dīn al‐Ṭūsī, Gerard of Cremona, Leonardo Fibonacci, Jordanus de Nemore, Roger Bacon[2] |

Life

The Banu Musa were the three sons of Mūsā ibn Shākir, who earlier in life had been a highwayman and astronomer in Khorasan of unknown pedigree.[5] After befriending al-Ma'mun, who was then a governor of Khorasan and staying in Marw, Musa was employed as an astrologer and astronomer.[6] After his death, his young sons were looked after by the court of al-Maʾmūn.[7] Al-Maʾmūn recognized the abilities of the three brothers and enrolled them in the famous House of Wisdom, a library and a translation center in Baghdad.[8]

Studying in the House of Wisdom under Yahya ibn Abi Mansur,[6] they participated in the efforts to translate ancient Greek works into Arabic by sending for Greek texts from the Byzantines, paying large sums for their translation, and learning Greek themselves.[7] On such trips, Muhammad met and recruited the famous mathematician and translator Thābit ibn Qurra. At some point Hunayn ibn Ishaq was also part of their team.[2] The brothers sponsored many scientists and translators, who were paid about 500 dīnārs a month. Had it not been for the brothers' efforts, many of the Greek texts that they translated would have been lost and forgotten.[5]

After the death of al-Ma'mun, the Banu Musa continued to work under the Caliphs al-Mu'tasim, al-Wathiq, and al-Mutawakkil. However, during the reign of al-Wathiq and al-Mutawakkil internal rivalries arose between the scholars in the House of Wisdom. At some point the Banu Musa became enemies of al-Kindi and contributed to his persecution by al-Mutawakkil. They were later employed by al-Mutawakkil to construct a canal for the new city of al-Jafariyya.[1]

Mathematics and mechanics

The Banu Musa had a different view on area and circumference from the Greeks. In the research they translated, the Greeks looked at volume and area more in terms of ratios, rather than giving them an actual numerical value. Most of them based such measurements relatively on another object's size. In one of their surviving publications, the Kitab Marifat Masahat Al-Ashkal (The Book of the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures) Banu Musa gave volume and area number values. This is evidence that they were not just translating and reproducing the Greek sources. They were actually building on concepts and coming up with some of their own original works.[1]

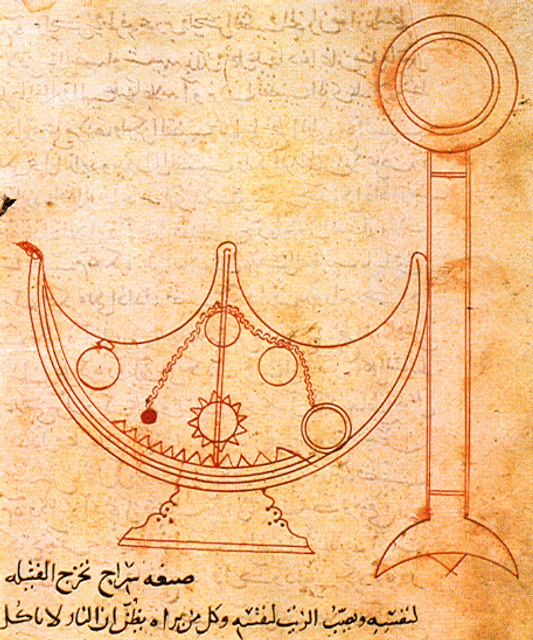

The most popular of their publications was the Kitāb al-Ḥiyal (The Tricks Book), which was mostly the work of Aḥmad, the middle brother, was a book filled with one hundred mechanical devices. There were some real practical inventions in the book including a lamp that would mechanically dim, alternating fountains, and a clamshell grab. Eighty of these devices were described as "trick vessels" that showed a real mastery of mechanics, with a real focus on the use of light pressure. Some of the devices seem to be replications of earlier Greek works, but the rest were much more advanced than what the Greeks had done.

Astronomy

They made many observations and contributions to the field of astronomy, writing nearly a dozen publications over their astronomical research. They made many observations on the sun and the moon. Al-Ma’mun had them go to a desert in Mesopotamia to measure the length of a degree. They also measured the length of a year to be 365 days and 6 hours.[1]

Politics

Although they were not made famous by their politics, they did have interests outside the world of science, mainly the oldest brother Muhammad. They were employed by the caliphs for many different projects, including the canal mentioned above, and they were also a part of a team of 20 hired to build the town of al-D̲j̲aʿfariyya for al-Mutawakkil. Taking on these types of civil projects naturally got them involved in the political scene in Baghdad. However, the height of Muhammad's political activity in the palace came towards the end of his life, during a time when Turkish commanders were starting to take control of the state. After al-Mutawakkil died, Muhammad helped al-Mustaʿīn get the nomination instead of the caliph's brother. When the caliph's brother besieged the city of Baghdad, Muhammad was sent to estimate the size of the army, and when the siege was over he was sent to get the terms of how al-Mustaʿīn would renounce the throne. This evidence shows where Muhammad ranks at that time. He was trusted and respected by the highest levels of authority at that time.

Works

The Banu Musa wrote almost 20 books, the majority of which are now lost.[2]

Automata

Most notable among their achievements is their work in the field of automation, which they utilized in toys and other entertaining creations. They have shown important advances over those of their Greek predecessors.[2]

The Book of Ingenious Devices describes 100 inventions; the ones which have been reconstructed work as designed. While designed primarily for amusement purposes, they employ innovative engineering technologies such as one-way and two-way valves able to open and close by themselves, mechanical memories, devices to respond to feedback, and delays. Most of these devices were operated by water pressure.[7]

Qarasṭūn, a treatise on weight balance.[8]

On Mechanical Devices, a work on pneumatic devices, written by Ahmad.[8]

A Book on the Description of the Instrument Which Sounds by Itself, about musical theory.[8]

Astronomy

Book on the First Motion of the Celestial Sphere (Kitāb Ḥarakāt al‐falak al‐ūlā), containing a critique of the Ptolemaic system. Muhammad in this book denied the existence of the Ptolemaic 9th sphere which Ptolemy thought was responsible for the motion.[2]

Book on the Mathematical Proof by Geometry That There Is Not a Ninth Sphere Outside the Sphere of the Fixed Stars, by Ahmad.

Book on The Construction of the Astrolabe, quoted by al-Biruni.[2]

Book on the Solar Year, was traditionally attributed to Thābit ibn Qurra, but recent research has shown that it was actually by the Bani Musa.[2]

On the Visibility of the Crescent, by Muhammad.

Book on the Beginning of the World, by Muhammad.

Book on the Motion of Celestial Spheres (Kitāb Ḥarakāt al‐aflāk), by Muhammad.

Book of Astronomy (Kitāb al‐Hayʾa), by Muhammad.

A book of zij, by Ahmad

Another book of zij, listed under the Banu Musa, mentioned by Ibn Yunus.[2]

Astrology

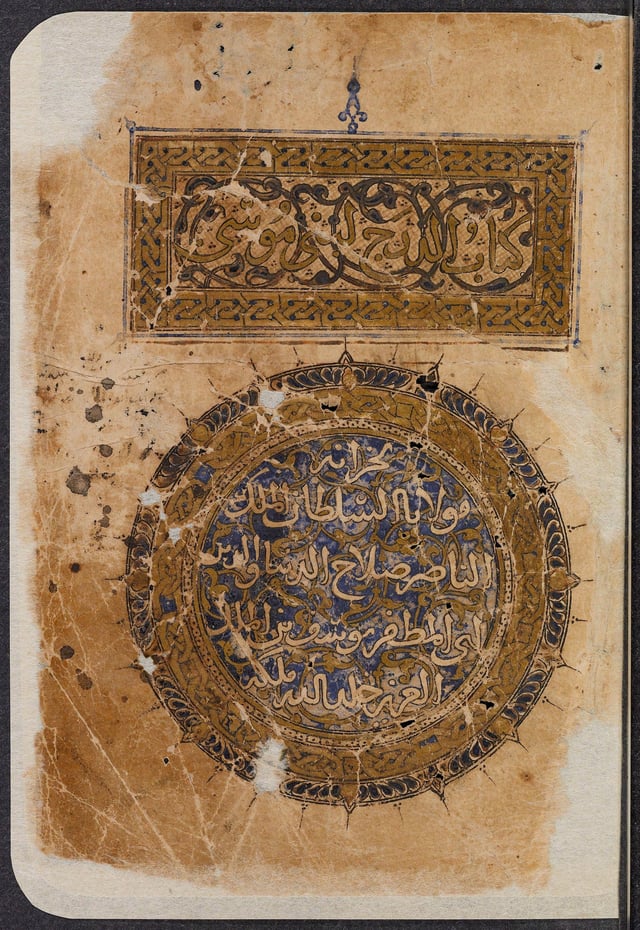

Cover of Kitāb al-Daraj (The book of degrees), by Ahmad, as found in the Saladin library, from before 1193 AD.

A translation of a Chinese work called A Book of Degrees on the Nature of Zodiacal Signs.

Kitāb al-Daraj (The book of degrees), by Ahmad.[6]

Mathematics

Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures, later edited by Naṣīr al‐Dīn al‐Ṭūsī in the 13th century. A Latin translation by Gerard of Cremona appeared the 12th century under the titles Liber trium fratrum de geometria and Verba filiorum Moysi filii Sekir. This treatise on geometry was used extensively in the Middle Ages, quoted by authors such as Thābit ibn Qurra, Ibn al‐Haytham, Leonardo Fibonacci (in his Practica geometriae), Jordanus de Nemore, and Roger Bacon.[2] Some theorems included in this book are not found in any work of the Greek mathematicians.[8]

Conic Sections of Apollonius of Perga, a recension of the Greek work, which was first translated to Arabic by Hilāl al-ḥimṣī and Thābit ibn Qurra.[8]

Book on an Oblong Round Figure, which contains a description of procedure used to draw an ellipse using a string, now called the gardener's construction.[2]

Reasoning on the Trisection of an Angle, by Aḥmad.

A treatise containing a discussion between Ahmad and Sanad ibn ʿAli.

Book on a Geometric Proposition Proved by Galen.

See also

Nuʿaym ibn Muḥammad ibn Mūsā, the son of Abu Ja'far Muhammad, wrote a mathematical treatise.

Inventions in the Muslim world

Islamic Golden Age

Islamic science