Austronesian languages

Austronesian languages

| Austronesian | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Austronesian peoples |

| Geographic distribution | Maritime Southeast Asia, Madagascar and parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Oceania, Easter Island, Taiwan and Hainan |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Austronesian |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | map |

| Glottolog | aust1307 [88][1] |

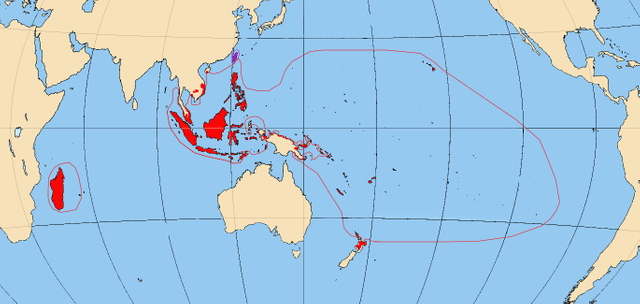

The Austronesian languages (/ˌɒstroʊˈniːʒən/, /ˌɒstrə/, /ˌɔːstroʊ-/, /ˌɔːstrə-/) are a language family widely spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, Madagascar and the islands of the Pacific Ocean. There are also a few speakers in continental Asia.[2] They are spoken by about 386 million people (4.9%). This makes it the fifth-largest language family by number of speakers. Major Austronesian languages include Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Javanese, and Filipino (Tagalog). The family contains 1,257 languages, which is the second most of any language family.[3]

In 1706, the Dutch scholar Adriaan Reland first observed similarities between the languages spoken in the Malay Archipelago and the Pacific Ocean.[4] In the 19th century, researchers (e.g. Wilhelm von Humboldt, Herman van der Tuuk) started to apply the comparative method to the Austronesian languages. The first extensive study on the history of the sound system was made by the German linguist Otto Dempwolff.[5] It also included a reconstruction of the Proto-Austronesian lexicon. The term Austronesian itself was coined by Wilhelm Schmidt. The word is derived from the German austronesisch, which is based on Latin auster "south wind" and Greek νῆσος "island").[6] The family is aptly named, because most Austronesian languages are spoken on islands. Only a few languages, such as Malay and the Chamic languages, are indigenous to mainland Asia. Many Austronesian languages have very few speakers. However, the major Austronesian languages are spoken by tens of millions of people. For example, Malay is spoken by 250 million people. This makes it the 8th most spoken language in the world. Approximately twenty Austronesian languages are official in their respective countries (see the list of major and official Austronesian languages).

By the number of languages they contain, Austronesian and Niger–Congo are the two largest language families in the world. They each contain roughly one-fifth of the world's languages. The geographical span of Austronesian was the largest of any language family before the spread of Indo-European in the colonial period. It ranged from Madagascar off the southeastern coast of Africa to Easter Island in the eastern Pacific. Hawaiian, Rapa Nui, Maori and Malagasy (spoken on Madagascar) are the geographic outliers.

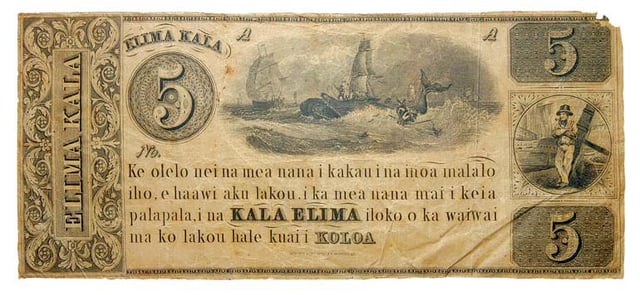

According to Robert Blust (1999), Austronesian is divided into several primary branches, all but one of which are found exclusively in Taiwan. The Formosan languages of Taiwan are grouped into as many as nine first-order subgroups of Austronesian. All Austronesian languages spoken outside Taiwan (including its offshore Yami language) belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch. These are sometimes called Extra-Formosan.

Most Austronesian languages lack a long history of written attestation. This makes reconstructing earlier stages – up to distant Proto-Austronesian – all the more remarkable. The oldest inscription in the Cham language, the Đông Yên Châu inscription dated to the mid-6th century AD at the latest, is the first attestation of any Austronesian language.

| Austronesian | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Austronesian peoples |

| Geographic distribution | Maritime Southeast Asia, Madagascar and parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Oceania, Easter Island, Taiwan and Hainan |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Austronesian |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | map |

| Glottolog | aust1307 [88][1] |

Structure

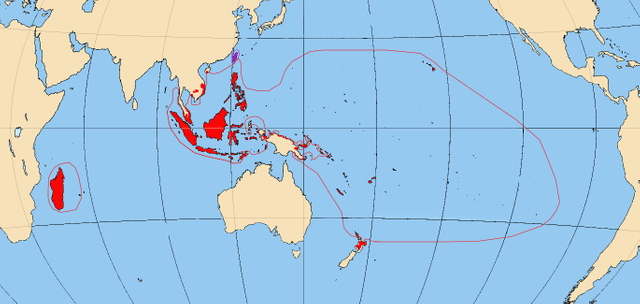

Banknote for 5 dollars, Hawaii, circa 1839, using Hawaiian language

It is difficult to make generalizations about the languages that make up a family as diverse as Austronesian. Very broadly, one can divide the Austronesian languages into three groups: Philippine-type languages, Indonesian-type languages and post-Indonesian type languages (Ross 2002):

The first group includes, besides the languages of the Philippines, the Austronesian languages of Taiwan, Sabah, North Sulawesi and Madagascar. It is primarily characterized by the retention of the original system of Philippine-type voice alternations, where typically three or four verb voices determine which semantic role the "subject"/"topic" expresses (it may express either the actor, the patient, the location and the beneficiary, or various other circumstantial roles such as instrument and concomitant). The phenomenon has frequently been referred to as focus (not to be confused with the usual sense of that term in linguistics). Furthermore, the choice of voice is influenced by the definiteness of the participants. The word order has a strong tendency to be verb-initial.

In contrast, the more innovative Indonesian-type languages, which are particularly represented in Malaysia and western Indonesia, have reduced the voice system to a contrast between only two voices (actor voice and "undergoer" voice), but these are supplemented by applicative morphological devices (originally two: the more direct *-i and more oblique *-an/-[a]kən), which serve to modify the semantic role of the "undergoer". They are also characterized by the presence of preposed clitic pronouns. Unlike the Philippine type, these languages mostly tend towards verb-second word-orders. A number of languages, such as the Batak languages, Old Javanese, Balinese, Sasak and several Sulawesi languages seem to represent an intermediate stage between these two types.[7][8]

Finally, in some languages, which Ross calls "post-Indonesian", the original voice system has broken down completely and the voice-marking affixes no longer preserve their functions.

The Austronesian languages tend to use reduplication (repetition of all or part of a word, as in wiki-wiki or agar-agar). Like many East and Southeast Asian languages, most Austronesian languages have highly restrictive phonotactics, with generally small numbers of phonemes and predominantly consonant–vowel syllables.

Lexicon

The Austronesian language family has been established by the linguistic comparative method on the basis of cognate sets, sets of words similar in sound and meaning which can be shown to be descended from the same ancestral word in Proto-Austronesian according to regular rules. Some cognate sets are very stable. The word for eye in many Austronesian languages is mata (from the most northerly Austronesian languages, Formosan languages such as Bunun and Amis all the way south to Māori). Other words are harder to reconstruct. The word for two is also stable, in that it appears over the entire range of the Austronesian family, but the forms (e.g. Bunun dusa; Amis tusa; Māori rua) require some linguistic expertise to recognise. The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database gives word lists (coded for cognateness) for approximately 1000 Austronesian languages.[9]

Classification

Distribution of the Austronesian languages, per Blust (1999)

The internal structure of the Austronesian languages is complex. The family consists of many similar and closely related languages with large numbers of dialect continua, making it difficult to recognize boundaries between branches. The first major step towards high-order subgrouping was Dempwolff’s recognition of the Oceanic subgroup (called Melanesisch by Dempwolff).[5] The special position of the languages of Taiwan was first recognized by Haudricourt (1965), who divided the Austronesian languages into three subgroups: Northern Austronesian (= Formosan), Eastern Austronesian (= Oceanic), and Western Austronesian (all remaining languages).

In a study that represents the first lexicostatistical classification of the Austronesian languages, Dyen (1965) presented a radically different subgrouping scheme. He posited 40 first-order subgroups, with the highest degree of diversity found in the area of Melanesia. The Oceanic languages are not recognized, but are distributed over more than 30 of his proposed first-order subgroups. Dyen’s classification was widely criticized and for the most part rejected (see e.g. Grace 1966), but several of his lower-order subgroups are still accepted (e.g. the Cordilleran languages, the Bilic languages or the Murutic languages).

Subsequently, the position of the Formosan languages as the most archaic group of Austronesian languages was recognized by Dahl (1973), followed by proposals from other scholars that the Formosan languages actually make up more than one first-order subgroup of Austronesian. Blust (1977) first presented the subgrouping model which is currently accepted by virtually all scholars in the field, with more than one first-order subgroup on Taiwan, and a single first-order branch encompassing all Austronesian languages spoken outside of Taiwan, viz. Malayo-Polynesian.

Malayo-Polynesian

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are—among other things—characterized by certain sound changes, such as the mergers of Proto-Austronesian (PAN) *t/*C to Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) *t, and PAN *n/*N to PMP *n, and the shift of PMP *S to PAN *h (Blust 2013:742).

There appear to have been two great migrations of Austronesian languages that quickly covered large areas, resulting in multiple local groups with little large-scale structure. The first was Malayo-Polynesian, distributed across the Philippines, Indonesia, and Melanesia. The Central Malayo-Polynesian languages are similar to each other not because of close genealogical relationships, but rather because they reflect strong substratum effects from non-Austronesian, Papuan languages. The second migration was that of the Oceanic languages into Polynesia and Micronesia (Greenhill, Blust & Gray 2008).

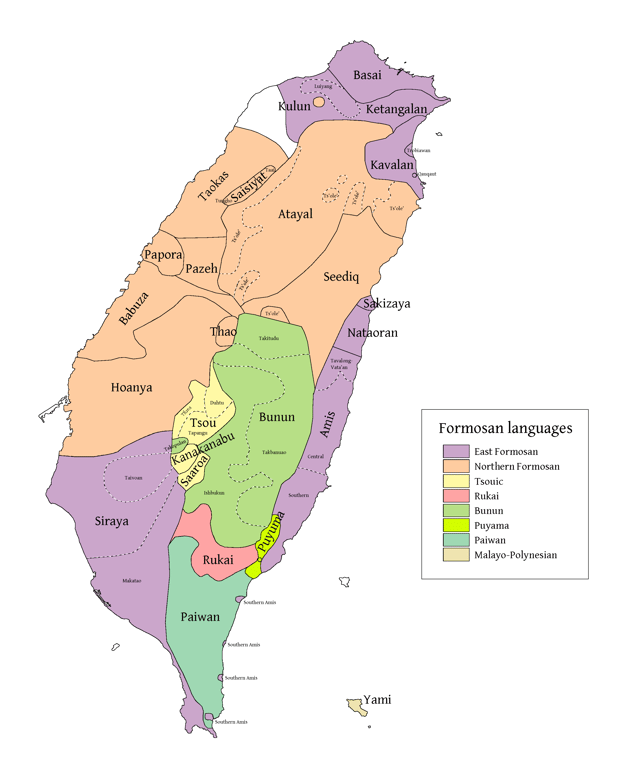

Primary branches on Taiwan (Formosan languages)

In addition to Malayo-Polynesian, thirteen Formosan subgroups are broadly accepted. The seminal article in the classification of Formosan—and, by extension, the top-level structure of Austronesian—is Blust (1999). Prominent Formosanists (linguists who specialize in Formosan languages) take issue with some of its details, but it remains the point of reference for current linguistic analyses. Debate centers primarily around the relationships between these families. Of the classifications presented here, Blust (1999) links two families into a Western Plains group, two more in a Northwestern Formosan group, and three into an Eastern Formosan group, while Li (2008) also links five families into a Northern Formosan group. Ross (2009) splits Tsouic, and notes that Tsou, Rukai, and Puyuma fall outside of reconstructions of Proto-Austronesian.

Other studies have presented phonological evidence for a reduced Paiwanic family of Paiwanic, Puyuma, Bunun, Amis, and Malayo-Polynesian, but this is not reflected in vocabulary. The Eastern Formosan peoples Basay, Kavalan, and Amis share a homeland motif that has them coming originally from an island called Sinasay or Sanasay (Li 2004). The Amis, in particular, maintain that they came from the east, and were treated by the Puyuma, amongst whom they settled, as a subservient group.[10]

Blust (1999)

Families of Formosan languages before Minnanese colonization of Taiwan, per Blust (1999)

(clockwise from the southwest)

Tsou language

Saaroa language

Kanakanabu language

Thao language a.k.a. Sao: Brawbaw and Shtafari dialects

Central Western Plains Babuza language: Taokas, Poavosa dialects; old Favorlang language Papora-Hoanya language: Papora, Hoanya dialects

Saisiyat language: Taai and Tungho dialects

Pazeh language a.k.a. Kulun

Atayal language

Seediq language a.k.a. Truku/Taroko

Northern (Kavalanic languages) Basay language: Trobiawa and Linaw–Qauqaut dialects Kavalan language Ketagalan language, or Ketangalan

Central (Ami) Amis proper Sakizaya

Siraya language

Mantauran, Tona, and Maga dialects of Rukai are divergent

(outside Formosa)

Li (2008)

Families of Formosan languages before Minnanese colonization, per Li (2008). The three languages in green (Bunun, Puyuma, Paiwan) may form a Southern Formosan branch, but this is uncertain.

This classification retains Blust's East Formosan, and unites the other northern languages. Li (2008) proposes a Proto-Formosan (F0) ancestor and equates it with Proto-Austronesian (PAN), following the model in Starosta (1995).[11] Rukai and Tsouic are seen as highly divergent, although the position of Rukai is highly controversial.[12]

F0: Proto-Formosan = Proto-Austronesian Rukai Mantauran Maga–Tona, Budai–Labuan–Taromak F1: (unnamed branch) Central (Tsouic) Tsou Southern Tsouic Saaroa Kanakanabu F2: (unnamed branch) Northern Formosan Northwestern (Plains) Saisiyat–Kulon–Pazeh Western Thao West Coast (Papora–Hoanya–Babuza–Taokas) Atayalic Squliq Atayal Ts'ole' Atayal (= C'uli') Seediq East Formosan Kavalan–Basay Siraya–Amis–Nataoran Sakizaya ? Southern [uncertain] Bunun Isbukun Northern and Central (Takitudu and Takbanuaz) Paiwan–Puyuma [uncertain]

Ross (2009)

In 2009, Malcolm Ross proposed a new classification of the Formosan language family based on morphological evidence from various Formosan languages.[13] He proposed that the current reconstructions for Proto-Austronesian actually correspond to an intermediate stage, which he terms "Proto-Nuclear Austronesian". Notably, Ross' classification does not support the unity of the Tsouic languages, instead considering the Southern Tsouic languages of Kanakanavu and Saaroa to be a separate branch. This supports Chang's (2006) claim that Tsouic is not a valid group.[14]

- Formosan

(Mantauran and Tona–Maga dialects are divergent)

Subdivisions not addressed, apart from Saaroa–Kanakanabu being separate from Tsou.

Major languages

History

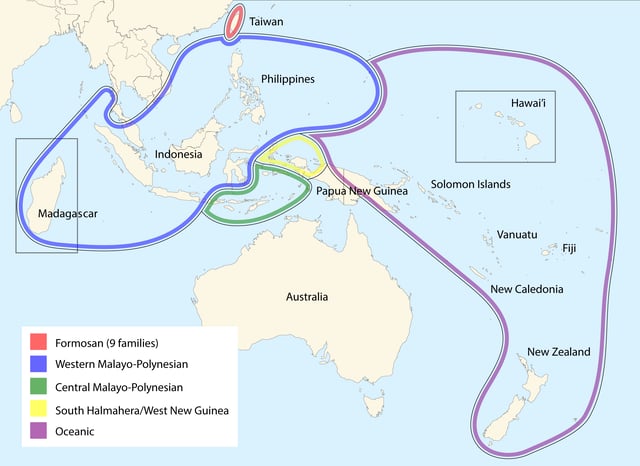

Austronesian languages expansion map. Periods are based on archeological studies, though the association of the archeological record and linguistic reconstructions is disputed.

From the standpoint of historical linguistics, the place of origin (in linguistic terminology, Urheimat) of the Austronesian languages (Proto-Austronesian language) is most likely the main island of Taiwan, also known as Formosa; on this island the deepest divisions in Austronesian are found, among the families of the native Formosan languages.

According to Robert Blust, the Formosan languages form nine of the ten primary branches of the Austronesian language family (Blust 1999). Comrie (2001:28) noted this when he wrote:

... the internal diversity among the... Formosan languages... is greater than that in all the rest of Austronesian put together, so there is a major genetic split within Austronesian between Formosan and the rest... Indeed, the genetic diversity within Formosan is so great that it may well consist of several primary branches of the overall Austronesian family.

At least since Sapir (1968), linguists have generally accepted that the chronology of the dispersal of languages within a given language family can be traced from the area of greatest linguistic variety to that of the least. For example, English in North America has large numbers of speakers, but relatively low dialectal diversity, while English in Great Britain has much higher diversity; such low linguistic variety by Sapir's thesis suggests a more recent origin of English in North America. While some scholars suspect that the number of principal branches among the Formosan languages may be somewhat less than Blust's estimate of nine (e.g. Li 2006), there is little contention among linguists with this analysis and the resulting view of the origin and direction of the migration. For a recent dissenting analysis, see (Peiros 2004). The protohistory of the Austronesian people can be traced farther back through time. To get an idea of the original homeland of the populations ancestral to the Austronesian peoples (as opposed to strictly linguistic arguments), evidence from archaeology and population genetics may be adduced. Studies from the science of genetics have produced conflicting outcomes. Some researchers find evidence for a proto-Austronesian homeland on the Asian mainland (e.g., Melton et al. 1998), while others mirror the linguistic research, rejecting an East Asian origin in favor of Taiwan (e.g., Trejaut et al. 2005). Archaeological evidence (e.g., Bellwood 1997) is more consistent, suggesting that the ancestors of the Austronesians spread from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan at some time around 8,000 years ago. Evidence from historical linguistics suggests that it is from this island that seafaring peoples migrated, perhaps in distinct waves separated by millennia, to the entire region encompassed by the Austronesian languages (Diamond 2000). It is believed that this migration began around 6,000 years ago (Blust 1999). However, evidence from historical linguistics cannot bridge the gap between those two periods. The view that linguistic evidence connects Austronesian languages to the Sino-Tibetan ones, as proposed for example by Sagart (2002), is a minority one. As Fox (2004:8) states:

Implied in... discussions of subgrouping [of Austronesian languages] is a broad consensus that the homeland of the Austronesians was in Taiwan. This homeland area may have also included the P'eng-hu (Pescadores) islands between Taiwan and China and possibly even sites on the coast of mainland China, especially if one were to view the early Austronesians as a population of related dialect communities living in scattered coastal settlements.

Linguistic analysis of the Proto-Austronesian language stops at the western shores of Taiwan; any related mainland language(s) have not survived. The only exceptions, the Chamic languages, derive from more recent migration to the mainland (Thurgood 1999:225).

Hypothesized relations

Genealogical links have been proposed between Austronesian and various families of East and Southeast Asia.

Austric

A link with the Austroasiatic languages in an 'Austric' phylum is based mostly on typological evidence. However, there is also morphological evidence of a connection between the conservative Nicobarese languages and Austronesian languages of the Philippines.

Austro-Tai

A competing Austro-Tai proposal linking Austronesian and Kra-Dai was first proposed by Paul K. Benedict, and is supported by Weera Ostapirat, Roger Blench, and Laurent Sagart, based on the traditional comparative method. Ostapirat (2005) proposes a series of regular correspondences linking the two families and assumes a primary split, with Kra-Dai speakers being the Austronesians who stayed behind in their Chinese homeland. Blench (2004) suggests that, if the connection is valid, the relationship is unlikely to be one of two sister families. Rather, he suggests that proto-Kra-Dai speakers were Austronesians who migrated to Hainan Island and back to the mainland from the northern Philippines, and that their distinctiveness results from radical restructuring following contact with Hmong–Mien and Sinitic. An extended version of Austro-Tai was hypothesized by Benedict who added the Japonic languages to the proposal as well.[15]

Sino-Austronesian

French linguist and Sinologist Laurent Sagart considers the Austronesian languages to be related to the Sino-Tibetan languages, and also groups the Kra–Dai languages as more closely related to the Malayo-Polynesian languages.[16] He also groups the Austronesian languages in a recursive-like fashion, placing Kra-Dai as a sister branch of Malayo-Polynesian. His methodology has been found to be spurious by his peers.

Japanese

Several linguists have proposed that Japanese is genetically related to the Austronesian family, cf. Benedict (1990), Matsumoto (1975), Miller (1967).

Some other linguists think it is more plausible that Japanese is not genetically related to the Austronesian languages, but instead was influenced by an Austronesian substratum or adstratum. Those who propose this scenario suggest that the Austronesian family once covered the islands to the north as well as to the south. Martine Robbeets (2017)[17] claims that Japanese is genetically related to the "Transeurasian" (= Macro-Altaic) languages, but underwent lexcial influence from "para-Austronesian", a presumed sister language of Proto-Austronesian. The linguist Ann Kumar (2009) proposed that some Austronesians migrated to Japan, possibly an elite-group from Java, and created the Japanese-hierarchical society and identifies 82 plausible cognates between Austronesian and Japanese.[18]

Ongan

Blevins (2007) proposed that the Austronesian and the Ongan protolanguage are the descendants of an Austronesian–Ongan protolanguage.[19] But this view is not supported by mainstream linguists and remains very controversial. Robert Blust (2014) rejects Blevins' proposal as far-fetched and based solely on chance resemblances and methodologically flawed comparisons.[20]

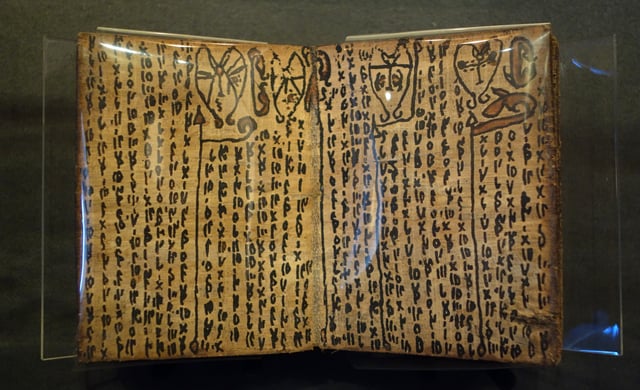

Writing systems

Manuscript from early 1800s using Batak alphabet

Most Austronesian languages have Latin-based writing systems today. Some non-Latin-based writing systems are listed below.

Brahmi script Kawi script Balinese alphabet - used to write Balinese and Sasak. Batak alphabet - used to write several Batak languages. Baybayin - used to write Tagalog and several Philippine languages. Bima alphabet - once used to write the Bima language. Buhid alphabet - used to write Buhid language. Hanunó'o alphabet - used to write Hanuno'o language. Javanese alphabet - used to write the Javanese language and several neighbouring languages like Madurese. Kerinci alphabet (Kaganga) - used to write the Kerinci language. Kulitan alphabet - used to write the Kapampangan language. Lampung alphabet - used to write Lampung and Komering. Lontara alphabet - used to write the Buginese, Makassarese and several languages of Sulawesi. Sundanese alphabet - used to write the Sundanese language. Rejang alphabet - used to write the Rejang language. Rencong alphabet - once used to write the Malay language. Tagbanwa alphabet - once used to write various Palawan languages. Lota alphabet - used to write the Ende-Li'o language. Cham alphabet - used to write Cham language.

Arabic script Pegon alphabet - used to write Javanese, Sundanese and Madurese as well as several smaller neighbouring languages. Jawi alphabet - used to write Malay, Acehnese, Banjar, Minangkabau, Tausug, Western Cham and others. Sorabe alphabet - once used to write several dialects of Malagasy language.

Hangul - once used to write the Cia-Cia language but the project is no longer active.

Dunging - used to write the Iban language but it was not widely used.

Avoiuli - used to write the Raga language.

Eskayan - used to write the Eskayan language, a secret language based on Boholano.

Woleai script (Caroline Island script) - used to write the Carolinian language (Refaluwasch).

Rongorongo - possibly used to write the Rapa Nui language.

Braille - used in Filipino, Malaysian, Indonesian, Tolai, Motu, Māori, Samoan, Malagasy, and many other Austronesian languages.

Comparison charts

Below are two charts comparing list of numbers of 1-10 and thirteen words in Austronesian languages; spoken in Taiwan, the Philippines, the Mariana Islands, Indonesia, Malaysia, Chams or Champa (in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam), East Timor, Papua, New Zealand, Hawaii, Madagascar, Borneo and Tuvalu.

See also

Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association

Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

List of Austronesian languages

List of Austronesian regions