Acceleration

Acceleration

| Acceleration | |

|---|---|

| a | |

| SI unit | m/s2, m·s−2, m s−2 |

| Dimension | LT |

In physics, acceleration is the rate of change of velocity of an object with respect to time. An object's acceleration is the net result of all forces acting on the object, as described by Newton's Second Law.[1] The SI unit for acceleration is metre per second squared (m⋅s−2). Accelerations are vector quantities (they have magnitude and direction) and add according to the parallelogram law.[2][3] The vector of the net force acting on a body has the same direction as the vector of the body's acceleration, and its magnitude is proportional to the magnitude of the acceleration, with the object's mass (a scalar quantity) as proportionality constant.

For example, when a car starts from a standstill (zero velocity, in an inertial frame of reference) and travels in a straight line at increasing speeds, it is accelerating in the direction of travel. If the car turns, an acceleration occurs toward the new direction. The forward acceleration of the car is called a linear (or tangential) acceleration, the reaction to which passengers in the car experience as a force pushing them back into their seats. When changing direction, this is called radial (as orthogonal to tangential) acceleration, the reaction to which passengers experience as a sideways force. If the speed of the car decreases, this is an acceleration in the opposite direction of the velocity of the vehicle, sometimes called deceleration or Retrograde burning in spacecraft.[4] Passengers experience the reaction to deceleration as a force pushing them forwards. Both acceleration and deceleration are treated the same, they are both changes in velocity. Each of these accelerations (tangential, radial, deceleration) is felt by passengers until their velocity (speed and direction) matches that of the uniformly moving car.

| Acceleration | |

|---|---|

| a | |

| SI unit | m/s2, m·s−2, m s−2 |

| Dimension | LT |

Definition and properties

Average acceleration

Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity.

Instantaneous acceleration

From bottom to top: an acceleration function a(t);the integral of the acceleration is the velocity function v (t);and the integral of the velocity is the distance function s (t).

Instantaneous acceleration, meanwhile, is the limit of the average acceleration over an infinitesimal interval of time. In the terms of calculus, instantaneous acceleration is the derivative of the velocity vector with respect to time:

(Here and elsewhere, if motion is in a straight line, vector quantities can be substituted by scalars in the equations.)

It can be seen that the integral of the acceleration function a (t) is the velocity function v (t); that is, the area under the curve of an acceleration vs. time (a vs. t) graph corresponds to velocity.

As acceleration is defined as the derivative of velocity, v, with respect to time t and velocity is defined as the derivative of position, x, with respect to time, acceleration can be thought of as the second derivative of x with respect to t:

Units

Acceleration has the dimensions of velocity (L/T) divided by time, i.e. L T−2. The SI unit of acceleration is the metre per second squared (m s−2); or "metre per second per second", as the velocity in metres per second changes by the acceleration value, every second.

Other forms

An object moving in a circular motion—such as a satellite orbiting the Earth—is accelerating due to the change of direction of motion, although its speed may be constant.

In this case it is said to be undergoing centripetal (directed towards the center) acceleration.

Proper acceleration, the acceleration of a body relative to a free-fall condition, is measured by an instrument called an accelerometer.

In classical mechanics, for a body with constant mass, the (vector) acceleration of the body's center of mass is proportional to the net force vector (i.e. sum of all forces) acting on it (Newton's second law):

where F is the net force acting on the body, m is the mass of the body, and a is the center-of-mass acceleration. As speeds approach the speed of light, relativistic effects become increasingly large.

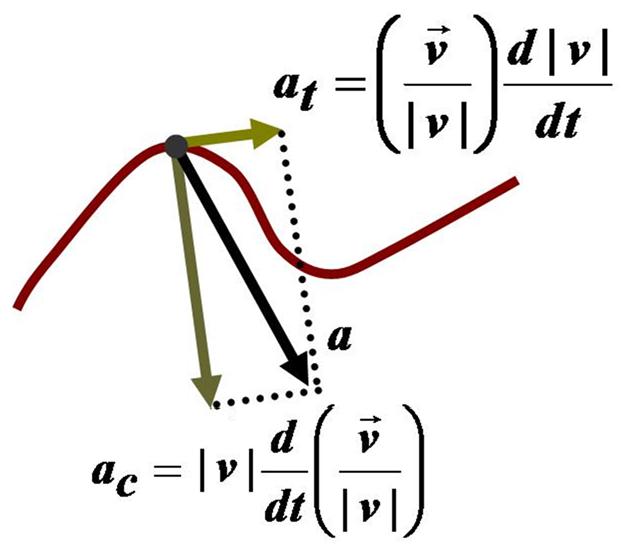

Tangential and centripetal acceleration

An oscillating pendulum, with velocity and acceleration marked.

Components of acceleration for a curved motion.

The velocity of a particle moving on a curved path as a function of time can be written as:

with v (t) equal to the speed of travel along the path, and

a unit vector tangent to the path pointing in the direction of motion at the chosen moment in time. Taking into account both the changing speed v(t) and the changing direction of ut, the acceleration of a particle moving on a curved path can be written using the chain rule of differentiation[5] for the product of two functions of time as:

where u n is the unit (inward) normal vector to the particle's trajectory (also called the principal normal), and r is its instantaneous radius of curvature based upon the osculating circle at time t. These components are called the tangential acceleration and the normal or radial acceleration (or centripetal acceleration in circular motion, see also circular motion and centripetal force).

Special cases

Uniform acceleration

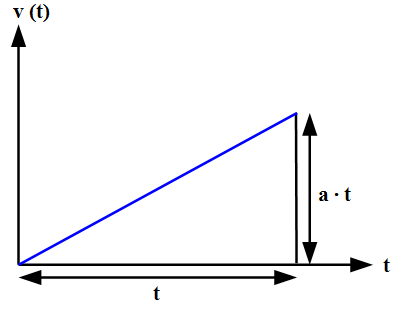

Calculation of the speed difference for a uniform acceleration

Uniform or constant acceleration is a type of motion in which the velocity of an object changes by an equal amount in every equal time period.

Because of the simple analytic properties of the case of constant acceleration, there are simple formulas relating the displacement, initial and time-dependent velocities, and acceleration to the time elapsed:[8]

where

is the elapsed time,

is the initial displacement from the origin,

is the displacement from the origin at time ,

is the initial velocity,

is the velocity at time, and

is the uniform rate of acceleration.

In particular, the motion can be resolved into two orthogonal parts, one of constant velocity and the other according to the above equations.

As Galileo showed, the net result is parabolic motion, which describes, e. g., the trajectory of a projectile in a vacuum near the surface of Earth.[9]

Circular motion

Acceleration vector a, not parallel to the radial motion but offset by the angular and Coriolis accelerations, nor tangent to the path but offset by the centripetal and radial accelerations.

Velocity vector v, always tangent to the path of motion.

Position vector r, always points radially from the origin.

In uniform circular motion, that is moving with constant speed along a circular path, a particle experiences an acceleration resulting from the change of the direction of the velocity vector, while its magnitude remains constant. The derivative of the location of a point on a curve with respect to time, i.e. its velocity, turns out to be always exactly tangential to the curve, respectively orthogonal to the radius in this point. Since in uniform motion the velocity in the tangential direction does not change, the acceleration must be in radial direction, pointing to the center of the circle. This acceleration constantly changes the direction of the velocity to be tangent in the neighboring point, thereby rotating the velocity vector along the circle.

This acceleration and the mass of the particle determine the necessary centripetal force, directed toward the centre of the circle, as the net force acting on this particle to keep it in this uniform circular motion. The so-called 'centrifugal force', appearing to act outward on the body, is a so-called pseudo force experienced in the frame of reference of the body in circular motion, due to the body's linear momentum, a vector tangent to the circle of motion.

Relation to relativity

Special relativity

The special theory of relativity describes the behavior of objects traveling relative to other objects at speeds approaching that of light in a vacuum.

Newtonian mechanics is exactly revealed to be an approximation to reality, valid to great accuracy at lower speeds. As the relevant speeds increase toward the speed of light, acceleration no longer follows classical equations.

As speeds approach that of light, the acceleration produced by a given force decreases, becoming infinitesimally small as light speed is approached; an object with mass can approach this speed asymptotically, but never reach it.

General relativity

Unless the state of motion of an object is known, it is impossible to distinguish whether an observed force is due to gravity or to acceleration—gravity and inertial acceleration have identical effects. Albert Einstein called this the equivalence principle, and said that only observers who feel no force at all—including the force of gravity—are justified in concluding that they are not accelerating.[10]

Conversions

| Base value | (Gal, or cm/s2) | (ft/s2) | (m/s2) | (Standard gravity], g0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gal, or cm/s2 | 1 | 0.0328084 | 0.01 | 0.00101972 |

| 1 ft/s2 | 30.4800 | 1 | 0.304800 | 0.0310810 |

| 1 m/s2 | 100 | 3.28084 | 1 | 0.101972 |

| 1g0 | 980.665 | 32.1740 | 9.80665 | 1 |

See also

Inertia

Jerk (physics)

Four-vector: making the connection between space and time explicit

Gravitational acceleration

Acceleration (differential geometry)

Orders of magnitude (acceleration)

Shock (mechanics)

Shock and vibration data logger measuring 3-axis acceleration

Space travel using constant acceleration

Specific force