29th Infantry Division (United States)

-RgI6cgP0uRhKSZxsQF834zihXBRar6)

29th Infantry Division (United States)

-RgI6cgP0uRhKSZxsQF834zihXBRar6)

| 29th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1917–1919, 1923–1968, 1985–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry unit |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | The Army National Guards of Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Florida, and West Virginia |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Belvoir, Virginia, U.S. |

| Nickname(s) | "Blue and Gray" (special designation)[1] |

| Motto(s) | "Twenty-nine, let's go!" |

| Engagements | World War I

Global War on Terrorism

|

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | MG John M. Epperly |

| Notable commanders | Charles Gould Morton Milton Reckord Leonard T. Gerow Charles H. Gerhardt H Steven Blum |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia | |

| Flag | |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (subdued) | |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (full color) | |

The 29th Infantry Division (29th ID), also known as the "Blue and Gray Division",[1] is an infantry division of the United States Army based in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. It is currently a formation of the U.S. Army National Guard and contains units from Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia.

Formed in 1917, the division deployed to France as a part of the American Expeditionary Force during World War I. Called up for service again in World War II, the division's 116th Regiment, attached to the First Infantry Division, was in the first wave of troops ashore during Operation Neptune, the landings in Normandy, France. It supported a special Ranger unit tasked with clearing strong points at Omaha Beach. The rest of the 29th ID came ashore later, then advanced to Saint-Lô, and eventually through France and into Germany.

Following the end of World War II, the division saw frequent reorganizations and deactivations. Although the 29th did not see combat through most of the next 50 years, it participated in numerous training exercises throughout the world. It eventually saw deployments to Bosnia (SFOR10) and Kosovo (KFOR) as command elements, and units of the division continue to deploy to locations such as Guantanamo Bay Naval Base and to the War in Afghanistan as a part of the Global War on Terrorism's Operation Enduring Freedom, and also to the Iraq War, as a part of its Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn.

| 29th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1917–1919, 1923–1968, 1985–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry unit |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | The Army National Guards of Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Florida, and West Virginia |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Belvoir, Virginia, U.S. |

| Nickname(s) | "Blue and Gray" (special designation)[1] |

| Motto(s) | "Twenty-nine, let's go!" |

| Engagements | World War I

Global War on Terrorism

|

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | MG John M. Epperly |

| Notable commanders | Charles Gould Morton Milton Reckord Leonard T. Gerow Charles H. Gerhardt H Steven Blum |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia | |

| Flag | |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (subdued) | |

| Shoulder sleeve insignia (full color) | |

History

The 29th Division was first constituted on paper 18 July 1917, three months after the American entry into World War I, in the U.S. Army National Guard.[6] [] The division's infantry units were the 57th Infantry Brigade, made up of the 113th and 114th Infantry Regiments, both from New Jersey, and the 58th Infantry Brigade, made up of the 115th Infantry Regiment from Maryland and 116th Infantry Regiment from Virginia. Its artillery units were Maryland's 110th Artillery Regiment; Virginia's 111th Field Artillery Regiment; and New Jersey's 112th Field Artillery Regiment. As the division was composed of men from states that had units that fought for both the North and South during the Civil War, it was nicknamed the "Blue and Gray" division, after the blue uniforms of the Union and the gray uniforms of the Confederate armies during the American Civil War.[7] The division was organized as a unit on 25 August 1917 at Camp McClellan, Alabama.[6] []

World War I

The division departed for the Western Front in June 1918 to join the American Expeditionary Force (AEF).[8] The division's advance detachment reached Brest, France on 8 June. In late September, the 29th received orders to join the U.S. First Army's Meuse-Argonne Offensive as part of the French XVII Corps. During its 21 days in combat,[9] the 29th Division advanced seven kilometers, captured 2,148 prisoners, and knocked out over 250 machine guns or artillery pieces. Thirty percent of the division became casualties—170 officers and 5,691 enlisted men were killed or wounded.[10] Shortly thereafter the Armistice with Germany was signed on November 11, 1918, ending hostilities between the Central Powers and the Allied Powers. The division returned to the United States in May 1919.[8] It demobilized on 30 May at Camp Dix, New Jersey,[6] [] though it remained an active National Guard unit.

Order of battle

Headquarters, 29th Division

57th Infantry Brigade 113th Infantry Regiment 114th Infantry Regiment 111th Machine Gun Battalion

58th Infantry Brigade 115th Infantry Regiment 116th Infantry Regiment 112th Machine Gun Battalion

54th Field Artillery Brigade 110th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm) 111th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm) 112th Field Artillery Regiment (155 mm) 104th Trench Mortar Battery

110th Machine Gun Battalion

104th Engineer Regiment

104th Field Signal Battalion

Headquarters Troop, 29th Division

104th Train Headquarters and Military Police 104th Ammunition Train 104th Supply Train 104th Engineer Train 104th Sanitary Train 113th, 114th, 115th, and 116th Ambulance Companies and Field Hospitals

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. Army began buildup and reorganization of its fighting forces. The division was called into active service on 3 February 1941.[8] Elements of the division were then sent to Fort Meade, Maryland for training.[10] The 57th and 58th Infantry Brigades were inactivated as part of an army-wide removal of brigades from divisions.[11] [] Instead, the core units of the division were its three infantry regiments, along with supporting units. On 12 March 1942, over three months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent American entrance into World War II, with this reorganization complete the division was redesignated as the 29th Infantry Division and began preparing for overseas deployment to Europe.[6] []

Order of battle

Headquarters, 29th Infantry Division

115th Infantry Regiment

116th Infantry Regiment

175th Infantry Regiment

Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 29th Infantry Division Artillery 110th Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm) 111th Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm) 224th Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm) 227th Field Artillery Battalion (155 mm)

121st Engineer Combat Battalion

104th Medical Battalion

29th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

Headquarters, Special Troops, 29th Infantry Division Headquarters Company, 29th Infantry Division 729th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company 29th Quartermaster Company 29th Signal Company Military Police Platoon Band

29th Counterintelligence Corps Detachment[8]

The 29th Infantry Division, under the command of Major General Leonard Gerow, was sent to England on 5 October 1942 on RMS Queen Mary.[8] It was based throughout England and Scotland, where it immediately began training for an invasion of northern Europe across the English Channel. In May 1943 the division moved to the Devon–Cornwall peninsula and started conducting simulated attacks against fortified positions.[10] At this time the division was assigned to V Corps of the U.S. First Army.[12][13] [] In July the divisional commander, Major General Gerow, was promoted to command V Corps and Major General Charles Hunter Gerhardt assumed command of the division, remaining in this post for the rest of the war.

Operation Overlord

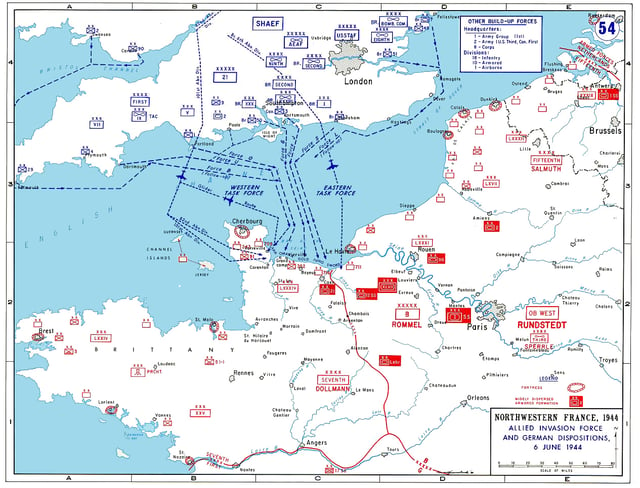

Allied battle plan for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy.

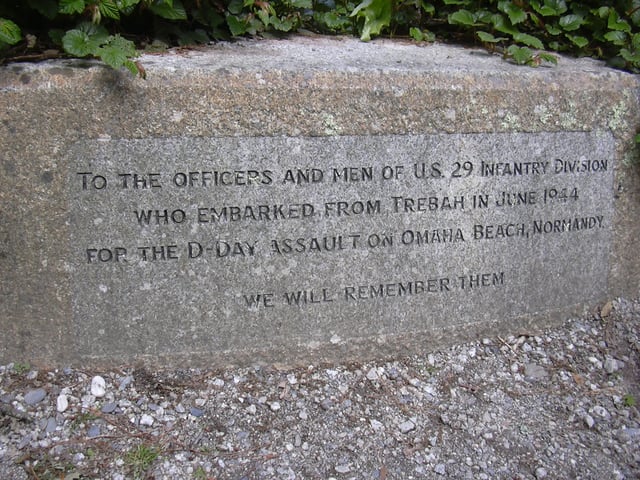

Memorial of the 29th Infantry Division's embarkation for D-Day in Trebah, United Kingdom.

D-Day of Operation Neptune, the cross-channel invasion of Normandy, finally came on June 6, 1944. Neptune was the assault phase of the larger Operation Overlord, codename for the Allied campaign to liberate France from the Germans. The 29th Infantry Division sent the 116th Infantry to support the western flank of the veteran 1st Infantry Division's 16th Infantry at Omaha Beach.[14] [] Omaha was known to be the most difficult of the five landing beaches, due to its rough terrain and bluffs overlooking the beach, which had been well fortified by its German defenders of the 352nd Infantry Division.[14] [] [15] The 116th Infantry was assigned four sectors of the beach; Easy Green, Dog Red, Dog White, and Dog Green. Soldiers of the 29th Infantry Division boarded a large number of attack transports for the D-Day invasion, among them landing craft, landing ship, tank, and landing ship, infantry ships and other vessels such as the SS Empire Javelin, USS Charles Carroll, and USS Buncombe County.[14] []

As the ships were traveling to the beach, the heavy seas, combined with the chaos of the fighting caused most of the landing force to be thrown off-course and most of the 116th Infantry missed its landing spots.[14] [] Most of the regiment's tank support, launched from too far off-shore, foundered and sank in the channel. The soldiers of the 116th Infantry were the first to hit the beach at 0630, coming under heavy fire from German fortifications. Company A, from the Virginia National Guard in Bedford was annihilated by overwhelming fire as it landed on the 116th's westernmost section of the beach, along with half of Company C of the 2nd Ranger Battalion which was landing to the west of the 116th.[14] [] The catastrophic losses suffered by this small Virginia community led to it being selected for the site of the National D-Day Memorial. The 1st Infantry Division's forces ran into similar fortifications on the eastern half of the beach, suffering massive casualties coming ashore. By 0830, the landings were called off for lack of space on the beach, as the Americans on Omaha Beach were unable to overcome German fortifications guarding the beach exits. Lieutenant General Omar Nelson Bradley, commanding the American First Army, considered evacuating the survivors and landing the rest of the divisions elsewhere.[13] [] [14] [] However, by noon, elements of the American forces had been able to organize and advance off the beach, and the landings resumed.[14] [] By nightfall, the division headquarters landed on the beach with about 60 percent of the division's total strength, and began organizing the push inland. On 7 June, a second wave of 20,000 reinforcements from both the 1st and 29th Divisions was sent ashore. By the end of D-Day, 2,400 men from the two divisions had become casualties on Omaha Beach.[14] [] Added to casualties at other beaches and air-drops made the total casualties for the Normandy landings 6,500 Americans and 3,000 British and Canadians, lighter numbers than expected.[15]

Breakout

The division cut across the Elle River and advanced slowly toward Saint-Lô, fighting bitterly in the Normandy hedge rows.[16] [] German reserves formed a new defensive front outside the town, and American forces fought a fierce battle with them two miles outside of the town.[13] [] German forces used the dense bocage foliage to their advantage, mounting fierce resistance in house-to-house fighting in the ravaged Saint-Lô. By the end of the fight, the Germans were relying on artillery support to hold the town following the depletion of the infantry contingent.[16] [] The 29th Division, which was already undermanned after heavy casualties on D-Day, was even further depleted in the intense fighting for Saint-Lô. Eventually, the 29th was able to capture the city in a direct assault, supported by airstrikes from P-47 Thunderbolts.[16] []

After taking Saint-Lô, on 18 July, the division joined in the battle for Vire, capturing that strongly held city by 7 August. it continued to face stiff German resistance as it advanced to key positions southeast of Saint-Lô[16] [] It was then reassigned to V Corps, and then again to VIII Corps.[12] Turning west, the 29th took part in the assault on Brest which lasted from 25 August until 18 September.[8] After a short rest, the division returned to XIX Corps and moved to defensive positions along the Teveren-Geilenkirchen line in Germany and maintained those positions through October.[8] On 16 November, the division began its drive to the Roer River, blasting its way through Siersdorf, Setterich, Durboslar, and Bettendorf, and reaching the Roer by the end of the month.[8] Heavy fighting reduced Jülich Sportplatz and the Hasenfeld Gut on 8 December.[8]

From 8 December 1944 to 23 February 1945, the division was assigned to XIII Corps and held defensive positions along the Rur and prepared for the next major offensive. The division was reassigned to XIX Corps,[12] and the attack jumped off across the Rur on 23 February, and carried the division through Jülich, Broich, Immerath, and Titz, to Mönchengladbach by 1 March 1945.[8] The division was out of combat in March. In early April the division was reassigned to XVI Corps, where the 116th Infantry helped mop up in the Ruhr area.[12] On 19 April 1945 the division, assigned to XIII Corps, pushed to the Elbe River and held defensive positions until 4 May.[8] Meanwhile, the 175th Infantry cleared the Klotze Forest. After V-E Day, the division was on military duty in the Bremen enclave.[8] It was assigned to XVI Corps again for this assignment.[12]

Losses, decorations, demobilization

Casualties

From July 1943, the 29th Infantry Division was commanded by Major General Charles H. Gerhardt. The division had such a high casualty rate that it was said that Gerhardt actually commanded three divisions: one on the field of battle, one in the hospital and one in the cemetery. The 29th Infantry Division lost 3,887 killed in action, 15,541 wounded in action, 347 missing in action, 845 prisoners of war, in addition to 8,665 non-combat casualties, during 242 days of combat. This amounted to over 200 percent of the division's normal strength. The division, in turn, took 38,912 German prisoners of war.

Soldiers of the 29th Infantry Division were awarded five Medals of Honor, 44 Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal, 854 Silver Star Medals, 17 Legion of Merit Medals, 24 Soldier's Medals, 6,308 Bronze Star Medals, and 176 Air Medals during the conflict. The division itself was awarded four distinguished unit citations and four campaign streamers for the conflict.[12] []

The division remained on occupation duty until the end of 1945. Camp Grohn near Bremen was the division headquarters until January 1946. The 29th Infantry Division returned to the United States in January 1946 and was demobilized and inactivated on 17 January 1946 at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey.[6] []

Reactivation

On 23 October 1946, the division was reactivated in Norfolk, Virginia.[6] [] However, its subordinate elements were not fully manned and activated for several years. It resumed its National Guard status, seeing weekend and summer training assignments but no major contingencies over the next few years.[10]

In 1959, the division was reorganized under the Pentomic five battle group division organization. Ewing's 29th Infantry Division: A Short History of a Fighting Division says that several Maryland infantry and engineer companies were reorganized to form 1st Med Tank Bn, 115th Armor; the 29th Aviation Company was established; and the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron, 183rd Armor, was established in Virginia as the division's reconnaissance squadron.[18] In 1963, the division was reorganized in accordance with the Reorganization Objective Army Divisions plan, eliminating its regimental commands in favor of brigades. The division took command of 1st Brigade, 29th Infantry Division and 2nd Brigade, 29th Infantry Division of the Virginia Army National Guard,[6] [] as well as 3rd Brigade, 29th Infantry Division of the Maryland Army National Guard.[6] [] The division continued its service in the National Guard under this new organization.[10]

In 1968, in the middle of the Vietnam War, the Army inactivated several National Guard and Reserve divisions as part of a realignment of resources. The 29th Infantry Division was one of the divisions inactivated. During that time, the division's subordinate units were reassigned to other National Guard divisions. 1st Brigade was inactivated, while 2nd Brigade was redesignated as the 116th Infantry Brigade, and the 3rd Brigade was redesignated as 3rd Brigade, 28th Infantry Division.[11] []

On 6 June 1984, 40 years after the landings on Omaha Beach, the Army announced that it would reactivate the 29th Infantry Division, organized as a light infantry division, as part of a reorganization of the National Guard.[10] On 30 September 1985, the division was reactivated at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, with a detachment in Maryland.[6] [] The 116th Infantry Brigade was redesignated the 1st Brigade, 29th Division, while the 58th Infantry Brigade became the 3rd Brigade.[11] [] That year, the division also received its distinctive unit insignia.[7]

Post Cold War

At the end of the Cold War, the Army saw further drawdowns and reductions in spending. The 29th Infantry Division was retained, however 2nd Brigade was inactivated in favor of assets from the inactivating 26th Infantry Division, which was redesignated the 26th Brigade, 29th Infantry Division.[11] []

The largest National Guard training exercise ever held in Virginia took place in July 1998, bringing units from the 29th Infantry Division together for one large infantry exercise. The Division Maneuver Exercise, dubbed Operation Chindit, brought together Guard units from Virginia and Maryland, as well as Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut and the District of Columbia. The exercise began with the insertion of troops from the 29th Infantry Division's 1st and 3rd Brigades by UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters into strategic landing zones. NATO-member forces trained with the 29th Infantry Division throughout the exercise.[10] In December 2008, the division also dispatched a task force to Camp Asaka near Tokyo, Japan for exercises with the Japanese Ground Self Defense Force called Yama Sakura 55, an bilateral exercise simulating an invasion of Japan.[19][20]

Present day

A 2005 oil painting depicting soldiers from the 2-124th participating in the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

29th Infantry Division soldiers conduct a large-scale exercise at Camp Bondsteel, Kosovo in May 2009.

29th Infantry Division sergeant in Afghanistan as part of the International Security Assistance Force, 2011.

Hundreds of soldiers from the 29th Infantry Division completed nine days of training on 16 June 2001 at Fort Polk, Louisiana, to prepare for their peacekeeping mission in Bosnia, as the second division headquarters to be deployed as a part of SFOR 10. In all, 2,085 National Guard soldiers from 16 states from Massachusetts to California served with the multinational force that operated in the US sector, MND-N. Their rotation began in October 2001 and lasted six months.[10]

The 29th Infantry Division completed a two-week warfighter exercise at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in late July 2003. Nearly 1,200 soldiers of the division participated in the training, which was overseen by First United States Army. Also engaged in the simulation war were about 150 soldiers of the New York Army National Guard's 42nd Infantry Division. The exercises covered a variety of operations, ranging from large scale contingencies to airborne and civil affairs operations.[10]

In March 2004, the 3rd Battalion 116th Infantry of 500+ soldiers was mobilized for 579 days in support of Operation Enduring Freedom - Afghanistan. Following 4 month train up, the battalion deployed to Bagram Air Base Afghanistan where the unit split into two operational elements. One element was stationed at Bagram where they were responsible for near base security and the theater-north Quick Reaction Force. They executed 5, 10, and 20 kilometer ring patrols to increase force security and stayed ready to react at a moments notice to deploy anywhere in Afghanistan to react to "troops in contact" that requested support. The other element moved south with the Bn Commander to control and shape operations in the Wardak and Ghazni provinces. It was here that the 116th would take its first casualties by enemy contact since World War II. SGT Bobby Beasley and SSG Craig Cherry were killed in an IED attack on a patrol in southern Ghazni near Gilan. Within the first three months, the unit would deploy nearly every soldier around Bagram, and throughout the Wardak and Ghazni provinces during the first Afghan elections in which President Hamid Karzai was elected. The unit would redeploy back to the United States in July 2005 highly decorated for its efforts during their mission following hundreds of successful combat patrols and engagements.

In 2005, 350 veterans, politicians, and soldiers representing the division went to Normandy and Paris, in France for the 60th anniversary of the D-Day landings. The Army National Guard organized a major ceremony for the 60th anniversary, as many of the veterans who participated in the invasion were in their 80s at that time, and the 60th anniversary was seen as the last major anniversary of the landings in which a large number of veterans could take part.[21]

The division underwent major reorganization in 2006. A special troops battalion was added to the division's command structure, and its three brigades were redesignated. It as organized around three brigades; the 30th Heavy Brigade Combat Team of North Carolina, the 116th Infantry Brigade Combat Team of Virginia, and the Combat Aviation Brigade, 29th Infantry Division of Maryland.[22]

In December 2006, the division took command of the Eastern region of Kosovo's peacekeeping force, to provide security in the region. The division's soldiers were part of a NATO multi-national task force consisting of units from the Ukraine, Greece, Poland, Romania, Armenia and Lithuania under the command of U.S. Army Brigadier General Douglas B. Earhart who concurrently served as the 29th's Deputy Commanding General. The division returned to Fort Belvoir in November 2007.

Approximately 72 Virginia and Maryland National Guard soldiers with the 29th ID deployed to Afghanistan from December 2010 to October 2011. As part of the 29th ID Security Partnering Team, the Soldiers were assigned to NATO's International Security Assistance Force Joint Command Security Partnering Team with the mission of assisting with the growth and development of the Afghan National Security Forces where they served as advisers and mentors to senior Afghan leaders. They were part of a NATO Coalition of 49 troop-contributing nations that Security Partnering personnel interacted with daily across Afghanistan.[23][24][25]

In 2014 the 29th ID twice sent soldiers to the Joint Multinational Readiness Center in Hohenfels, Germany to assist in the training of U.S. and multinational soldiers preparing to head to Kosovo as part of the Kosovo Force[31] mission. The 29th ID soldiers performed as the KFOR staff, serving as subject matter experts, enforcing KFOR orders, systems and procedures, and working with JMRC to help the deploying troops achieve their training objectives.[32][33]

The 29th ID currently serves as the Domestic All-Hazards Response Team (DART) in FEMA Regions 1 through 5 (states east of the Mississippi). In this role the 29th ID is prepared to assist state National Guard in their service to governors and citizens during an incident response.[34] The DART provides defense support of civil authority capabilities in response to a catastrophic event. The DART conducts joint reception, staging, onward-movement and Integration of inbound OPCON forces and establishes base support installations and /or forward operating bases for sustaining operations.[35]

On 24 July 2015, Brig. Gen. Blake C. Ortner took command of the 29th Infantry Division from Maj. Gen. Charles W. Whittington.[36]

On 19 December 2016 the 29th Infantry Division assumed command of U.S. Army Central’s intermediate division headquarters, Task Force Spartan, at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait. This deployment includes 450 Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina Army National Guard soldiers and is the first time the 29th Infantry Division has been a part of Third Army since 1944, during WWII.[37]

More than 80 members of the 29th deployed to Jordan in August 2016 where they assumed command of the military’s joint operations center there to support Operation Inherent Resolve.[2] Soldiers of the 29th led engagements and joint training with the Jordan Armed Forces and allied countries before returning in July 2017.[3]

On 5 May 2018, Brig. Gen. John M. Epperly took command of the 29th Infantry Division from Maj. Gen. Blake C. Ortner.[38]

Current organization

Structure 29th Infantry Division

The 29th Infantry Division exercises training and readiness oversight of the following units;[39] they are not organic:

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/23px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/35px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/46px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 2x|29th Infantry Division SSI.svg|h23|w23]] 29th Infantry Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion[10] Headquarters and Support Company, Fort Belvoir, Virginia (VA NG) A (Operations) Company, Fort Belvoir, Virginia (VA NG) B (Intelligence and Sustainment) Company, Annapolis, Maryland (MD NG) C (Signal) Company, Cheltenham, Maryland (MD NG) [[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/US_Army_29th_Inf_Div_Band_Tab.png/45px-US_Army_29th_Inf_Div_Band_Tab.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/US_Army_29th_Inf_Div_Band_Tab.png/68px-US_Army_29th_Inf_Div_Band_Tab.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/US_Army_29th_Inf_Div_Band_Tab.png/90px-US_Army_29th_Inf_Div_Band_Tab.png 2x|US Army 29th Inf Div Band Tab.png|h19|w45]] 29th Infantry Division Band (VA NG)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/30th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/26px-30th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/30th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/39px-30th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/30th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/52px-30th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 2x|30th Infantry Division SSI.svg|h41|w26]] 30th Armored Brigade Combat Team (30th ABCT) (NC NG)[10] Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Company (BHHC) 1st Squadron, 150th Cavalry Regiment (WV NG) 1st Battalion, 252nd Armor Regiment (NC NG) 4th Battalion, 118th Infantry Regiment (SC NG) 1st Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment (NC NG) 1st Battalion, 113th Field Artillery Regiment (1-113th FAR) (NC NG) 236th Brigade Engineer Battalion (236th BEB) 230th Brigade Support Battalion (230th BSB) (NC NG)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/53rd_Infantry_Brigade_SSI.svg/23px-53rd_Infantry_Brigade_SSI.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/53rd_Infantry_Brigade_SSI.svg/35px-53rd_Infantry_Brigade_SSI.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/53rd_Infantry_Brigade_SSI.svg/46px-53rd_Infantry_Brigade_SSI.svg.png 2x|53rd Infantry Brigade SSI.svg|h35|w23]] 53rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (53rd IBCT) (FL NG) BHHC 1st Squadron, 153rd Cavalry Regiment 1st Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment 2nd Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 167th Infantry Regiment (AL NG) 2nd Battalion, 116th Field Artillery Regiment (2-116th FAR) 753rd Brigade Engineer Battalion (753rd BEB) 53rd Brigade Support Battalion (53rd BSB)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/23px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/35px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/46px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 2x|29th Infantry Division SSI.svg|h23|w23]]116th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (116th IBCT) (VA NG)[10] BHHC 2nd Squadron, 183rd Cavalry Regiment 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment 3rd Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 149th Infantry Regiment (KY NG) 1st Battalion, 111th Field Artillery Regiment (1-111th FAR) 229th Brigade Engineer Battalion (229th BEB) 429th Brigade Support Battalion (429th BSB)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/23px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/35px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg/46px-29th_Infantry_Division_SSI.svg.png 2x|29th Infantry Division SSI.svg|h23|w23]] Combat Aviation Brigade, 29th Infantry Division (CAB) (MD NG)[40] 1st Battalion, 285th Aviation Regiment (AZ NG) 2nd Battalion, 224th Aviation Regiment (VA NG) 8th Battalion, 229th Aviation Regiment (USAR) 1st Battalion, 111th Aviation Regiment (FL NG) 1204th Aviation Support Battalion (1204th ASB)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/142FABdeSSI.svg/23px-142FABdeSSI.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/142FABdeSSI.svg/35px-142FABdeSSI.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/142FABdeSSI.svg/46px-142FABdeSSI.svg.png 2x|142FABdeSSI.svg|h23|w23]]142nd Field Artillery Brigade (142nd FAB)[41][42] Headquarters & Headquarters Battery (HHB), 142nd Field Artillery Brigade (142nd FAB): Fayetteville, Arkansas 1st Battalion, 142nd Field Artillery Regiment (1-142nd FAR): Harrison, Arkansas 2nd Battalion, 142nd Field Artillery Regiment (2-142nd FAR): Fort Smith, Arkansas 217th Brigade Support Battalion (217th BSB) : Booneville, Arkansas F Battery, 142nd Field Artillery Regiment (F-142nd FAR) : Fayetteville 142nd Signal Company Fayetteville

Honors

Unit decorations

Campaign streamers

Legacy

The 29th Infantry Division has been featured numerous times in popular media, particularly for its role on D-Day. The division's actions on Omaha Beach are featured prominently in the 1962 film The Longest Day,[43] as well as in the 1998 film Saving Private Ryan.[44][45] Soldiers of the division are featured in other films and television with smaller roles, such as in the 2005 film War of the Worlds.[46]

The 29th Infantry Division is also featured in numerous video games related to World War II. The division's advance through Normandy and Europe is featured in the games Close Combat, Company of Heroes and Call of Duty 3, in which the player assumes the role of a soldier of the division.[47]

A number of soldiers serving with the 29th Infantry Division have gone on to achieve notability for various reasons. Among them are highly decorated soldier Joseph A. Farinholt, soccer player James Ford, United States federal judge Alfred D. Barksdale,[48] and historian Lawrence C. Wroth,[49] generals Milton Reckord,[50] Norman Cota,[51] Charles D. W. Canham, and Donald Wilson.[52] Major Thomas D. Howie who commanded 3d Battalion, 116th Infantry during the battle of St. Lo became immortalized as "The Major of St. Lo" for the honors rendered to him after being killed in action.[53]

See also

Joseph Balkoski, military historian and author of a five-volume history of the 29th Division

Saving Private Ryan beach landing scene