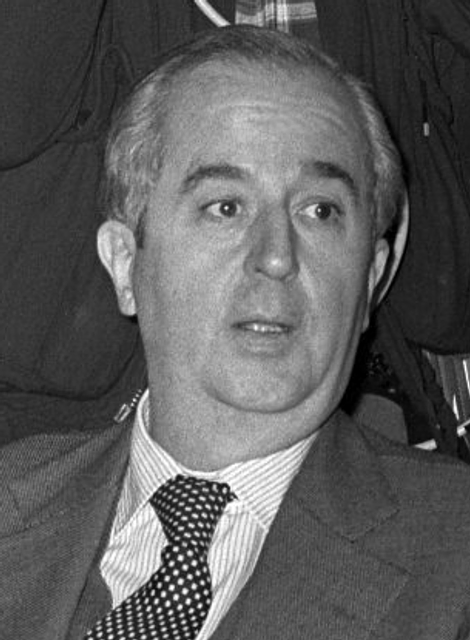

Édouard Balladur

Édouard Balladur

Édouard Balladur | |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 29 March 1993 – 10 May 1995 | |

| President | François Mitterrand |

| Preceded by | Pierre Bérégovoy |

| Succeeded by | Alain Juppé |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 20 March 1986 – 12 May 1988 | |

| President | François Mitterrand |

| Prime Minister | Jacques Chirac |

| Preceded by | Pierre Bérégovoy |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Bérégovoy |

| Secretary General of the Presidency | |

| In office 5 April 1973 – 2 April 1974 | |

| President | Georges Pompidou |

| Preceded by | Michel Jobert |

| Succeeded by | Bernard Beck |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1929-05-02)2 May 1929 Smyrna, Turkey |

| Political party | Union for a Popular Movement |

| Spouse(s) | Marie-Josèphe Delacour |

| Children | 4 |

| Occupation | Senior official |

Édouard Balladur (French: [edwaʁ baladyʁ]; born 2 May 1929)[1] is a French politician who served as Prime Minister of France under François Mitterrand from 29 March 1993 to 10 May 1995. He unsuccessfully ran for president in the 1995 French presidential election, coming in third place. At age 90, Balladur is currently the oldest living former French Prime Minister.

Édouard Balladur | |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 29 March 1993 – 10 May 1995 | |

| President | François Mitterrand |

| Preceded by | Pierre Bérégovoy |

| Succeeded by | Alain Juppé |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 20 March 1986 – 12 May 1988 | |

| President | François Mitterrand |

| Prime Minister | Jacques Chirac |

| Preceded by | Pierre Bérégovoy |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Bérégovoy |

| Secretary General of the Presidency | |

| In office 5 April 1973 – 2 April 1974 | |

| President | Georges Pompidou |

| Preceded by | Michel Jobert |

| Succeeded by | Bernard Beck |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1929-05-02)2 May 1929 Smyrna, Turkey |

| Political party | Union for a Popular Movement |

| Spouse(s) | Marie-Josèphe Delacour |

| Children | 4 |

| Occupation | Senior official |

Biography

In 1957, Balladur married Marie-Josèphe Delacour, with whom he had four sons.

Early political career

Balladur started his political career in 1964 as an advisor to Prime Minister Georges Pompidou. After Pompidou's election as President of France in 1969, Balladur was appointed under-secretary general of the presidency then secretary general from 1973 to Pompidou's death in 1974.

He returned to politics in the 1980s as a supporter of Jacques Chirac. A member of the Neo-Gaullist Rally for the Republic (RPR) party, he was the theoretician behind the "cohabitation government" from 1986 to 1988, explaining that if the right won the legislative election, it could govern with Chirac as prime minister without Socialist Party President François Mitterrand's resignation. As Minister of Economy and Finance, he sold off a large number of public companies and abolished the wealth tax.

Balladur appeared as an unofficial deputy Prime Minister in the cabinet led by Chirac. He took a major part in the adoption of liberal and pro-European policies by Chirac and the RPR. After Chirac's defeat at the 1988 presidential election, part of the RPR held him responsible of the abandonment of Gaullist doctrine, but he kept the confidence of Chirac.

Prime Minister

When the RPR/UDF coalition won the 1993 legislative election, Chirac declined to become Prime Minister again in a second "cohabitation" with President Mitterrand, and Balladur became Prime Minister. He was faced with a difficult economic situation, but he did not want to make the political errors of the previous cohabitation government. If he failed to impose his project of minimum income for youth, he led a moderate liberal policy in economy.[3] Conveying the image of a quiet conservative, he did not question the wealth tax (reestablished by the Socialists in 1988). Despite corruption affairs affecting some of his ministers, who he forced to resign (thus lending his name to the so-called "Balladur jurisprudence"), he became very popular and had the support of influential media.

1995 presidential election

When he became Prime Minister, Balladur had promised Chirac that he would not enter the 1995 presidential election, and that he would support Chirac's candidacy. However a number of right-wing politicians advised Balladur to run for the presidency in 1995. He went back on his promise to Chirac and entered the campaign. When he announced his candidacy, four months before the election, he was considered the favourite. In the polls, he led Chirac by almost 20 points. However, from the position of an outsider, Chirac criticized Balladur as representing "dominant ideas", and the difference between the two decreased quickly. The revelation of a bugging scandal which implicated Balladur also contributed to a drop in his popularity among voters.

In the first round of the election, Balladur finished in third place with 18.6% of the vote behind the Socialist candidate Lionel Jospin and Chirac. He was thus eliminated from the final run-off election between the top two candidates, which Chirac won.

Chirac immediately appointed Alain Juppé to replace Balladur as Prime Minister. Despite Chirac declaring that he and Balladur had been "friends for 30 years", Balladur's decision to stand against him greatly strained their relationship. As a result, the "Balladuriens" who had supported him in the presidential election, such as Nicolas Sarkozy, were ostracized from the new Chirac administration.

Later political career

Balladur failed to win the elections for the presidency of the Île-de-France region in 1998, the RPR nomination for the mayoralty of Paris in 2001, and the Chair of the National Assembly in 2002. He presided over the National Assembly's foreign affairs committee during his last parliamentary term (2002–2007). Since the 1980s, he had advocated the unification of the right-wing groupings into a single large party, but it was Chirac who managed the feat, with the creation of the Union for a Popular Movement in 2002.

Following the 2007 French presidential election, Nicolas Sarkozy nominated Balladur to the head of a committee for institutional reforms. The constitutional revision was approved by the Parliament in July 2008.

From 1968 to 1980, Balladur was president of the French company of the Mont Blanc Tunnel while occupying various other positions in ministerial staff. Following the 1999 deadly accident in the tunnel, he gave evidence to the court judging the case in 2005 about the security measures he had or had not taken. Balladur claimed that he always took security seriously, but that it was difficult to agree on anything with the Italian company operating the Italian part of the tunnel. From 1977 to 1986, he was president of Générale de Service Informatique (later merged into IBM Global Services), making him one of the few French politicians with business experience.

In 2006, he announced that he would not run again for re-election in 2007 as a member of Parliament for the 15th arrondissement of Paris, a conservative stronghold.

In 2008, Balladur visited the United States to speak at an event organized by the Streit Council, a Washington-based think tank. Balladur presented his latest book, in which he outlined a concept for a "Union of the West".[4]

Balladur is often caricatured as aloof, aristocratic, and arrogant in media, such as the Canard Enchaîné weekly or the Les Guignols de l'info TV show. Incidentally, the percentage of French government ministers who were also members of Le Siècle peaked at 72% under Balladur's Prime Ministership (1993–95).[5]

Political offices held

Governmental functions Prime minister: 1993–1995. Minister of State, Minister of Economy and Finances: 1986–1988.

Electoral mandates

National Assembly of France Member of the National Assembly of France for Paris: Elected in March 1986, but he became minister / 1988–1993 (Became Prime minister in 1993) / 1995–2007. Elected in 1986, reelected in 1988, 1993, 1995, 1997, 2002.

Regional Council Regional councillor of Ile-de-France: March–April 1998 (Resignation).

Municipal Council Councillor of Paris: 1989–2008. Reelected in 1995, 2001.

Rwanda genocide

On 5 August 2008, the government of Rwanda issued a report accusing Balladur of involvement in the 1994 Rwanda genocide that killed 800,000 people. He and other French officials were accused in the report of giving political, military, diplomatic, and logistical support during the genocide to Rwanda’s extremist government and the Hutu forces that slaughtered minority Tutsis and politically moderate Hutus.[6]

Cabinet

(29 March 1993 – 10 May 1995)

Édouard Balladur – Prime Minister

Alain Juppé – Minister of Foreign Affairs

François Léotard – Minister of Defense

Charles Pasqua – Minister of the Interior and Regional Planning

Edmond Alphandéry – Minister of Economy

Nicolas Sarkozy – Minister of the Budget and Spokesman for the Government

Gérard Longuet – Minister of Industry, Foreign Trade, Posts, and Telecommunications

Michel Giraud – Minister of Labour, Employment, and Vocational Training

Pierre Méhaignerie – Minister of Justice

François Bayrou – Minister of National Education

Philippe Mestre – Minister of Veterans and War Victims

Jacques Toubon – Minister of Culture and Francophonie

Jean Puech – Minister of Agriculture and Fish

Michèle Alliot-Marie – Minister of Youth and Sports

Dominique Perben – Minister of Overseas Departments and Territories

Bernard Bosson – Minister of Transport, Tourism, and Equipment

Simone Veil – Minister of Social Affairs, Health, and City

Michel Roussin – Minister of Cooperation

Hervé de Charette – Minister of Housing

Alain Carignon – Minister of Communication

André Rossinot – Minister of Civil Service

Alain Madelin – Minister of Companies and Economic Development

François Fillon – Minister of Higher Education and Research

Changes

19 July 1994 – Minister of Communication Alain Carignon leaves the Cabinet and the Ministry is abolished.

17 October 1994 – José Rossi succeeds Longuet as Minister of Industry, Foreign Trade, Posts, and Telecommunications.

12 November 1994 – Bernard Debré succeeds Roussin as Minister of Cooperation