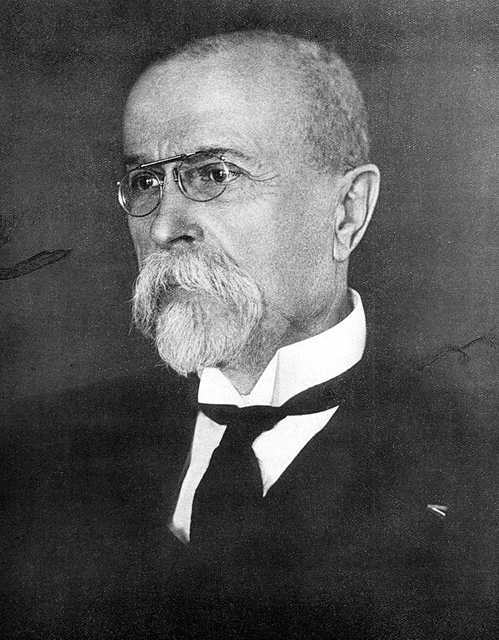

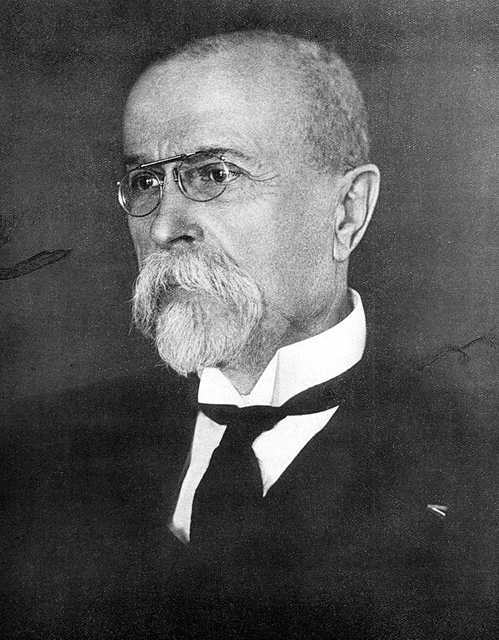

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk | |

|---|---|

| 1st President of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 14 December 1935 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Edvard Beneš |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1850-03-07)7 March 1850 Hodonín, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 14 September 1937(1937-09-14)(aged 87) Lány, Czechoslovakia |

| Political party | Young Czech Party (1890–1893) Realist Party (1900–1918) |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte Garrigue |

| Children | Alice (1879–1966) Herbert (1880–1915) Jan (1886–1948) Eleonor (1890–1890) Olga (1891–1978) |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Profession | Philosopher |

| Signature | |

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (Czech: [ˈtomaːʃ ˈɡarɪk ˈmasarɪk]), sometimes anglicised Thomas Masaryk (7 March 1850 – 14 September 1937), was a Czechoslovak politician, statesman, sociologist and philosopher. Until 1914, he advocated restructuring the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a federal state. With the help of the Allied Powers, Masaryk gained independence for a Czechoslovak Republic as World War I ended in 1918. He founded Czechoslovakia and served as its first president, and so is called by some Czechs the "President Liberator"[1] (Czech: Prezident Osvoboditel).

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk | |

|---|---|

| 1st President of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 14 December 1935 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Edvard Beneš |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1850-03-07)7 March 1850 Hodonín, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 14 September 1937(1937-09-14)(aged 87) Lány, Czechoslovakia |

| Political party | Young Czech Party (1890–1893) Realist Party (1900–1918) |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte Garrigue |

| Children | Alice (1879–1966) Herbert (1880–1915) Jan (1886–1948) Eleonor (1890–1890) Olga (1891–1978) |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Profession | Philosopher |

| Signature | |

Early life

Masaryk was born to a poor, working-class family in the predominantly Catholic city of Hodonín, Moravia, in Moravian Slovakia (in the present-day Czech Republic, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The nearby Slovak village of Kopčany, the home of his father Josef, also claims to be his birthplace.[2] Masaryk grew up in the village of Čejkovice, in South Moravia, before moving to Brno to study.[3]

His father, Jozef Masárik, was born in Kopčany (then in the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary). Jozef Masárik was a carter and, later, the steward and coachman at the imperial estate in nearby town Hodonín. Tomáš's mother, Teresie Masaryková (née Kropáčková), was a Moravian of Slavic origin who received a German education. A cook at the estate, she met Masárik and they married on 15 August 1849.

Education

After grammar school in Brno and Vienna from 1865[4] to 1872, Masaryk attended the University of Vienna and was a student of Franz Brentano.[5] He received his Ph.D. from the university in 1876 and completed his habilitation thesis, Der Selbstmord als sociale Massenerscheinung der modernen Civilisation (Suicide as a Social Mass Phenomenon of Modern Civilization) there in 1879.[5] From 1876 to 1879, Masaryk studied in Leipzig with Wilhelm Wundt and Edmund Husserl.[6] He married Charlotte Garrigue, whom he had met while a student in Leipzig, on 15 March 1878. They lived in Vienna until 1881, when they moved to Prague.

Masaryk was appointed professor of philosophy at the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University, the Czech-language part of Charles University, in 1882. He founded Athenaeum, a magazine devoted to Czech culture and science, the following year.[7] Athenaeum, edited by Jan Otto, was first published on 15 October 1883.

Masaryk challenged the validity of the epic poems Rukopisy královedvorský a zelenohorský, supposedly dating to the early Middle Ages and presenting a false, nationalistic Czech chauvinism which he was strongly opposed. He also contested the Jewish blood libel during the 1899 Hilsner trial.

Early career

Masaryk served in the Reichsrat from 1891 to 1893 with the Young Czech Party and from 1907 to 1914 in the Czech Realist Party, which he had founded in 1900. At that time, he was not yet campaigning for Czech and Slovak independence from Austria-Hungary. Masaryk helped Hinko Hinković defend the Croat-Serb Coalition during their 1909 Vienna political trial; its members were sentenced to a total of over 150 years in prison, with a number of death sentences.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Masaryk concluded that the best course was to seek independence for Czechs and Slovaks from Austria-Hungary. He went into exile in December 1914 with his daughter, Olga, staying in several places in Western Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States and Japan. Masaryk began organizing Czechs and Slovaks outside Austria-Hungary during his exile, establishing contacts which would be crucial to Czechoslovak independence. He delivered lectures and wrote a number of articles and memoranda supporting the Czechoslovak cause. Masaryk was pivotal in establishing the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia as an effective fighting force on the Allied side during World War I, when he held a Serbian passport.[8] In 1915 he was one of the first staff members of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (now part of University College London), where the student society and senior common room are named after him. Masaryk became professor of Slavic Research at King's College in London, lecturing on the problem of small nations.

Czechoslovak Legion and US visit

During the war, Masaryk's intelligence network of Czech revolutionaries provided critical intelligence to the allies. His European network worked with an American counterespionage network of nearly 80 members, headed by E.V. Voska. Voska and his network, who (as Habsburg subjects) were presumed to be German supporters, spied on German and Austrian diplomats. Among other achievements, the intelligence from these networks was critical in uncovering the Hindu–German Conspiracy in San Francisco.[9][10][11][12] Masaryk began teaching at London University in October 1915. He published "Racial Problems in Hungary", with ideas about Czechoslovak independence. In 1916, Masaryk went to France to convince the French government of the necessity of dismantling Austria-Hungary. After the 1917 February Revolution he proceeded to Russia to help organize the Czechoslovak Legion, a group dedicated to Slavic resistance to the Austrians.

On 5 August 1914, the Russian High Command authorized the formation of a battalion recruited from Czechs and Slovaks in Russia. The unit went to the front in October 1914, and was attached to the Russian Third Army.

From its start, Masaryk wanted to develop the legion from a battalion to a formidable military formation. To do so, however, he realized that he would need to recruit Czech and Slovak prisoners of war (POWs) in Russian camps. In late 1914, Russian military authorities permitted the legion to enlist Czech and Slovak POWs from the Austro-Hungarian army; the order was rescinded in a few weeks, however, because of opposition from other areas of the Russian government. Despite continuing efforts to persuade the Russian authorities to change their minds, the Czechs and Slovaks were officially barred from recruiting POWs until the summer of 1917.

Under these conditions, the Czechoslovak armed unit in Russia grew slowly from 1914 to 1917. In early 1916, it was reorganized as the First Czecho-Slovak Rifle Regiment. After the Czechoslovak troops' performance in July 1917 at the Battle of Zborov (when they overran Austrian trenches), the Russian provisional government granted Masaryk and the Czechoslovak National Council permission to recruit and mobilize Czech and Slovak volunteers from the POW camps. Later that summer a fourth regiment was added to the brigade, which was renamed the First Division of the Czechoslovak Corps in Russia (Československý sbor na Rusi, also known as the Czechoslovak Legion – Československá legie). A second division of four regiments was added to the legion in October 1917, raising its strength to about 40,000 by 1918.

Masaryk traveled to the United States in 1918, where he convinced President Woodrow Wilson of the righteousness of his cause. On 5 May 1918, over 150,000 Chicagoans filled the streets to welcome him; Chicago was the center of Czechoslovak immigration to the United States, and the city's reception echoed his earlier visits to the city and his visiting professorship at the University of Chicago in 1902 (Masaryk had lectured at the university in 1902 and 1907). He also had strong links to the United States, with his marriage to an American citizen and his friendship with Chicago industrialist Charles R. Crane, who had Masaryk invited to the University of Chicago and introduced to the highest political circles (including Wilson). Except of the president Wilson and the secretary of the state Robert Lansing this was Ray Stannard Baker , W. Phillips, Polk, Long, Lane, D. F. Houston and the French ambassador Jean Jules Jusserand. And Bernard Baruch, Vance McCormick, Edward N. Hurley, Samuel M. Vauclain, Colonel House too. On Chicago meeting in 8 October 1918 Chicago industrialist Samuel Insull introduced him as the president of future Czechoslovak Republik de facto and mentioned his legions[13]. In 18 October 1918 he submitted to president Thomas Woodrow Wilson "Washington Declaration" created with the help of Masaryk American friends (Louis Brandeis, Ira Bennett, Gutzon Borglum, Franklin K. Lane, Edward House, Miller, Nichols, Calfee, Warrick, Stearn and Czech Jaroslav Císař) as the basic document for the foundation of a new independent Czechoslovak state. Speaking on 26 October 1918 as head of the Mid-European Union in Philadelphia, Masaryk called for the independence of Czechoslovaks and the other oppressed peoples of central Europe.

Leader of Czechoslovakia

Masaryk and his daughter, Olga, returning from exile in 21 December 1918

Masaryk at Prague Old Town Square in 1932

With the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, the Allies recognized Masaryk as head of the provisional Czechoslovak government. On 14 November of that year, he was elected president of Czechoslovakia by the National Assembly in Prague while he was in New York. On 22 December, Masaryk publicly denounced the Germans in Czechoslovakia as settlers and colonists.[14]

Masaryk was re-elected three times: in May 1920, 1927, and 1934 Czechoslovak presidential election. A provision in the 1920 constitution exempted him from its two-term limit.

On paper, Masaryk's presidential power was limited; the framers of the constitution intended to create a parliamentary system in which the prime minister and cabinet hold actual power. However, a complex system of proportional representation made it all but impossible for one party to win a majority; no party ever won more than 25 percent of the vote. Usually, ten or more parties received the 2.6 percent of votes needed for seats in the National Assembly. These factors resulted in frequent changes of government; there were ten cabinets, headed by nine statesmen, during Masaryk's tenure. His presence gave Czechoslovakia a large measure of stability. This stability, combined with his domestic and international prestige, gave Masaryk's presidency more power and influence than the framers of the constitution intended.

He used his authority in Czechoslovakia to create the Hrad (the Castle), an extensive, informal political network. In 1925, he considered abolishing women's suffrage and limiting the voting rights of young men and soldiers, who tended to support the Communists.[15] In April 1926, Masaryk and Beneš looked at launching a coup to establish a dictatorship.[16] Masaryk led a propaganda campaign to personally seize all the credit for Czechoslovakian independence and built a cult of personality around himself as "President-Liberator", a philosopher statesman, the embodiment of the state, truth and virtue, a military hero loved by the soldiers, a flawless democrat and the apotheosis of Czech history.[17] Though constantly propagated through school history textbooks as well as by Czech and foreign popular historians such as Emil Ludwig, the cult was rejected by the national minorities and by Czech Catholics and communists.[18]

Masaryk visited France, Belgium, England, Egypt and the Mandate for Palestine in 1923 and 1927. With Herbert Hoover, he sponsored the first Prague International Management Congress, a July 1924 gathering of 120 global labour experts (60 was from United States of America), organized with Masaryk Academy of Labour.[19] After the rise of Adolf Hitler, Masaryk was one of the first political figures in Europe to voice concern. He resigned from office on 14 December 1935 because of old age and poor health, and was succeeded by Edvard Beneš.

Death and legacy

Statue of Masaryk in Prague

Masaryk died less than two years after leaving office, at the age of 87, in Lány, Czechoslovakia (present-day Czech Republic). He did not live to see the Munich Agreement or the Nazi occupation of his country, and was known as the Grand (Great) Old Man of Europe.

Commemoration and awards

As the founding father of Czechoslovakia, Masaryk is revered as George Washington is in the United States. Czechs and Slovaks regard him as a symbol of democracy.

Commemorations of Masaryk have been held annually in the Lány cemetery on his birthday and day of death (7 March and 14 September) since 1989.

The Czechoslovak, then Czech Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, established in 1990, is an honour awarded to individuals who have made outstanding contributions to humanity, democracy and human rights.

Masaryk University in Brno, founded in 1919 as Czechoslovakia's second university, was named after him when it was founded; after 30 years as Univerzita Jana Evangelisty Purkyně v Brně, it was renamed for Masaryk in 1990.

He is commemorated by a number of statues, busts and plaques. Although most are in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Masaryk has a statue on Embassy Row in Washington, D.C. and in the Midway Plaisance park in Chicago and is memorialised in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park rose garden. A plaque with a portrait of Masaryk is on the wall of a Rachiv, Ukraine hotel where he reportedly resided from 1917 to 1918, and a bust was erected in 2002 on Druzhba Narodiv Square (Friendship of Nations Square) in Uzhhorod, Ukraine.

Avenida Presidente Masaryk (President Masaryk Avenue) is a main thoroughfare in Mexico City, and Masaryktown, Florida is named for him.[20] Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk near Haifa, was founded largely by Jewish immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Tel Aviv has a Masaryk Square; he had visited the city in 1927. Streets in Zagreb, Belgrade, Dubrovnik, Daruvar, Varaždin, Novi Sad and Split are named Masarykova ulica, and a main thoroughfare in Ljubljana is named after Masaryk. Streets named Thomas Masaryk can be found in Geneva [21] and Bucharest.

Asteroid 1841 Masaryk, discovered by Lubos Kohoutek, is named after him.[22]

In popular culture

A United Nations Expeditionary Force starship in Joe Haldeman's 1974 science-fiction novel, The Forever War, is named Masaryk. A photograph of Masaryk leaning out of a train window, waving to and shaking hands with supporters, is the front cover for Faith No More's 1997 album Album of the Year. Its liner notes include the funeral of an old man, with the words "pravda vítězí" ("Truth prevails") adorning the coffin. The statement is the motto of the Czech Republic.

Philosophy

Masaryk's motto was "Do not fear, and do not steal" (Czech: Nebát se a nekrást). A philosopher and an outspoken rationalist and humanist, he emphasised practical ethics reflecting the influence of Anglo-Saxon philosophers, French philosophy and—in particular—the work of 18th-century German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, who is considered the founder of nationalism. Masaryk was critical of German idealism and Marxism.[23]

Books

He wrote several books in Czech, including The Czech Question (1895), The Problems of Small Nations in the European Crisis (1915), The New Europe (1917), and The World Revolution (Svĕtová revoluce; 1925) translated to English as The Making of a State (1927). Karel Čapek wrote a series of articles, Hovory s T.G.M. ("Conversations with T.G.M."), which were later collected as Masaryk's autobiography.

Personal life

Masaryk married Charlotte Garrigue in 1878, and took her family name as his middle name. They met in Leipzig, Germany, and became engaged in 1877. Garrigue was born in Brooklyn to a Protestant family with French Huguenots among their ancestors. She became fluent in Czech, and published articles in a Czech magazine. Hardships during the war took their toll, and she died in 1923. Their son, Jan, was foreign minister in the Czechoslovak government-in-exile (1940–1945) and in the governments from 1945 to 1948. They had four other children: Herbert, Alice, Eleanor, and Olga.

Family tree

| Tomáš Masaryk | Charlotte Garrigue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alice | Herbert | Jan | Eleanor | Olga | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||