New York City Subway

New York City Subway

| |||

Top: A 1 train made up of R62A cars leaves the 125th Street station. Bottom: An E train made up of R160A cars enters the World Trade Center station. | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Government of New York City | ||

| Area served | The Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens | ||

| Locale | New York City | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 36 lines[1] 28 services (1 planned)[2] | ||

| Number of stations | 472[11] (MTA total count)[3][4] 424 unique stations[4][11] (when compared to international standards) 14 planned[3] | ||

| Daily ridership | 5,580,845 (weekdays, 2017)[11] 3,156,673 (Saturdays, 2017)[11] 2,525,481 (Sundays, 2017)[11] | ||

| Annual ridership | 1,727,366,607 (2017)[11] | ||

| Website | mta.info/nyct [411] | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | October 27, 1904 (Original subway) July 3, 1868[16] (first elevated, rapid transit operation) October 9, 1863 (first railroad operation)[5] | ||

| Operator(s) | New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) | ||

| Number of vehicles | 6,418[17] | ||

| Headway | Peak hours: 2–5 minutes[18] Off-peak: 10–20 minutes[18] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 245 miles (394 km)[19] (route length) 691 mi (1,112 km)[19] (track length, revenue) 850 mi (1,370 km)[20] (track length, total) | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 81⁄2 in(1,435 mm)standard gauge[20] | ||

| Electrification | 600–650 V (DC) third rail; normally 625V[20][21] | ||

| Average speed | 17 mph (27 km/h)[22] | ||

| Top speed | 55 mph (89 km/h)[22] | ||

| |||

The New York City Subway is a rapid transit system owned by the City of New York and leased to the New York City Transit Authority,[23] a subsidiary agency of the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).[24] Opened in 1904, the New York City Subway is one of the world's oldest public transit systems, one of the most-used, and the one with the most stations.[25] The New York City Subway is the largest rapid transit system in the world by number of stations, with 472 stations in operation[26] (424 if stations connected by transfers are counted as single stations).[11] Stations are located throughout the boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx.

The system offers service 24 hours per day, every day of the year, though some routes may operate only part-time.[26] By annual ridership, the New York City Subway is the busiest rapid transit system in both the Western Hemisphere and the Western world, as well as the ninth-busiest rapid transit rail system in the world.[27] In 2017, the subway delivered over 1.72 billion rides, averaging approximately 5.6 million daily rides on weekdays and a combined 5.7 million rides each weekend (3.2 million on Saturdays, 2.5 million on Sundays).[11] On September 23, 2014, more than 6.1 million people rode the subway system, establishing the highest single-day ridership since ridership was regularly monitored in 1985.[28][6]

The system is also one of the world's longest. Overall, the system contains 245 miles (394 km) of routes,[20][29] translating into 665 miles (1,070 km) of revenue track[20] and a total of 850 miles (1,370 km) including non-revenue trackage.[20] Of the system's 28 routes or "services" (which usually share track or "lines" with other services), 25 pass through Manhattan, the exceptions being the G train, the Franklin Avenue Shuttle, and the Rockaway Park Shuttle. Large portions of the subway outside Manhattan are elevated, on embankments, or in open cuts, and a few stretches of track run at ground level. In total, 40% of track is aboveground.[30] Many lines and stations have both express and local services. These lines have three or four tracks. Normally, the outer two are used by local trains, while the inner one or two are used by express trains. Stations served by express trains are typically major transfer points or destinations.[26]

| |||

Top: A 1 train made up of R62A cars leaves the 125th Street station. Bottom: An E train made up of R160A cars enters the World Trade Center station. | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Government of New York City | ||

| Area served | The Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens | ||

| Locale | New York City | ||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 36 lines[1] 28 services (1 planned)[2] | ||

| Number of stations | 472[11] (MTA total count)[3][4] 424 unique stations[4][11] (when compared to international standards) 14 planned[3] | ||

| Daily ridership | 5,580,845 (weekdays, 2017)[11] 3,156,673 (Saturdays, 2017)[11] 2,525,481 (Sundays, 2017)[11] | ||

| Annual ridership | 1,727,366,607 (2017)[11] | ||

| Website | mta.info/nyct [411] | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | October 27, 1904 (Original subway) July 3, 1868[16] (first elevated, rapid transit operation) October 9, 1863 (first railroad operation)[5] | ||

| Operator(s) | New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) | ||

| Number of vehicles | 6,418[17] | ||

| Headway | Peak hours: 2–5 minutes[18] Off-peak: 10–20 minutes[18] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 245 miles (394 km)[19] (route length) 691 mi (1,112 km)[19] (track length, revenue) 850 mi (1,370 km)[20] (track length, total) | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 81⁄2 in(1,435 mm)standard gauge[20] | ||

| Electrification | 600–650 V (DC) third rail; normally 625V[20][21] | ||

| Average speed | 17 mph (27 km/h)[22] | ||

| Top speed | 55 mph (89 km/h)[22] | ||

| |||

History

The City Hall station of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line opened on October 27, 1904

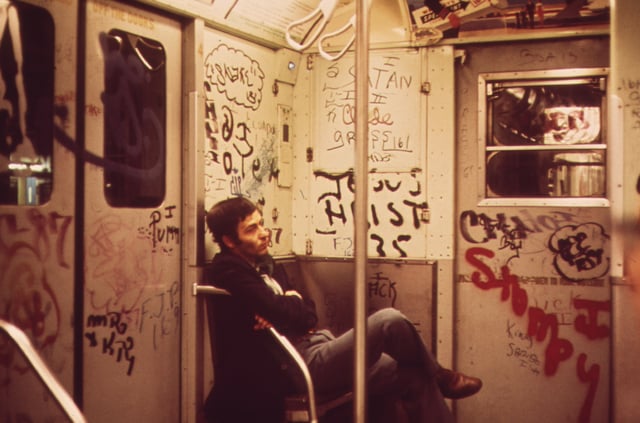

Graffiti became a notable symbol of declining service during the 1970s.

The Cortlandt Street station partially collapsed as a result of the collapse of the World Trade Center.

Alfred Ely Beach built the first demonstration for an underground transit system in New York City in 1869 and opened it in February 1870.[33][34] His Beach Pneumatic Transit only extended 312 feet (95 m) under Broadway in Lower Manhattan operating from Warren Street to Murray Street[33] and exhibited his idea for an atmospheric railway as a subway. The tunnel was never extended for political and financial reasons.[35] Today, no part of this line remains as the tunnel was completely within the limits of the present day City Hall Station under Broadway.[36][37][38][39])

The Great Blizzard of 1888 helped demonstrate the benefits of an underground transportation system.[40] A plan for the construction of the subway was approved in 1894, and construction began in 1900.[41] Even though the underground portions of the subway had yet to be built, several above-ground segments of the modern-day New York City Subway system were already in service by then. The oldest structure still in use opened in 1885 as part of the BMT Lexington Avenue Line in Brooklyn[42][43][44][45][46] and is now part of the BMT Jamaica Line.[47] The oldest right-of-way, which is part of the BMT West End Line near Coney Island Creek, was in use in 1864 as a steam railroad called the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Rail Road.[48][49][50]

The first underground line of the subway opened on October 27, 1904, almost 36 years after the opening of the first elevated line in New York City, which became the IRT Ninth Avenue Line.[51][52][53] The 9.1-mile (14.6 km) line, then called the "Manhattan Main Line", ran from City Hall station northward under Lafayette Street (then named Elm Sreet) and Park Avenue (then named Fourth Avenue) before turning westward at 42nd Street. It then curved northward again at Times Square, continuing under Broadway before terminating at 145th Street station in Harlem.[51] Its operation was leased to the Interborough Rapid Transit Company and over 150,000 passengers[54] paid the 5¢ fare to ride it on the first day of operation.[55]

By the late 1900s and early 1910s, the lines had been consolidated into two privately owned systems, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, later Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation, BMT) and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). The city built most of the lines and leased them to the companies.[56] The first line of the city-owned and operated Independent Subway System (IND) opened in 1932;[57] this system was intended to compete with the private systems and allow some of the elevated railways to be torn down, but stayed within the core of the City due to its small startup capital.[23] This required it to be run 'at cost', necessitating fares up to double the five-cent fare popular at the time.[58]

In 1940, the city bought the two private systems. Some elevated lines ceased service immediately while others closed soon after.[59] Integration was slow, but several connections were built between the IND and BMT;[60][61][62] these now operate as one division called the B Division. Since the IRT tunnels, sharper curves, and stations are too small and therefore can not accommodate B Division cars, the IRT remains its own division, the A Division.[63] However, many passenger transfers between stations of all three former companies have been created, allowing the entire network to be treated as a single unit.[64]

Organized in 1934 by transit workers of the BRT, IRT, and IND,[67] the Transport Workers Union of America Local 100 remains the largest and most influential local of the labor unions.[68] Since the union's founding, there have been three union strikes over contract disputes with the MTA:[69] 12 days in 1966,[70][71] 11 days in 1980,[72] and three days in 2005.[73][74]

By the 1970s and 1980s, the New York City Subway was at an all-time low.[75][76] Ridership had dropped to 1910s levels, and graffiti and crime were rampant. Maintenance was poor, and delays and track problems were common. Still, the NYCTA managed to open six new subway stations in the 1980s,[77][78] make the current fleet of subway cars graffiti-free, as well as order 1,775 new subway cars.[79] By the early 1990s, conditions had improved significantly, although maintenance backlogs accumulated during those 20 years are still being fixed today.[76]

Entering the 21st century, progress continued despite several disasters. The September 11 attacks resulted in service disruptions on lines running through Lower Manhattan, particularly the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, which ran directly underneath the World Trade Center.[80] Sections of the tunnel, as well as the Cortlandt Street station, which was directly underneath the Twin Towers, were severely damaged. Rebuilding required the suspension of service on that line south of Chambers Street. Ten other nearby stations were closed for cleanup. By March 2002, seven of those stations had reopened. Except for Cortlandt Street, the rest reopened on September 15, 2002, along with service south of Chambers Street.[81][82][81][83] Cortlandt Street reopened on September 8, 2018.[84][85]

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded several underwater tunnels and other facilities near New York Harbor, as well as trackage over Jamaica Bay. The immediate damage was fixed within six months but long-term resiliency and rehabilitation projects continue. Among the more notable Sandy recovery projects include the restoration of the new South Ferry station from 2012 to 2017; the full closure of the Montague Street Tunnel from 2013 to 2014; and the partial 14th Street Tunnel shutdown from 2019 to 2020.[86]

Construction methods

A stretch of subway track on the 7 Subway Extension.

When the IRT subway debuted in 1904,[51][52] the typical tunnel construction method was cut-and-cover.[87][88] The street was torn up to dig the tunnel below before being rebuilt from above.[87][88] Traffic on the street above would be interrupted due to the digging up of the street.[89] Temporary steel and wooden bridges carried surface traffic above the construction.[90]

Contractors in this type of construction faced many obstacles, both natural and man-made. They had to deal with rock formations and ground water, which required pumps. Twelve miles of sewers, as well as water and gas mains, electric conduits, and steam pipes had to be rerouted. Street railways had to be torn up to allow the work. The foundations of tall buildings often ran near the subway construction, and in some cases needed underpinning to ensure stability.[91]

This method worked well for digging soft dirt and gravel near the street surface.[87] However, tunnelling shields were required for deeper sections, such as the Harlem and East River tunnels, which used cast-iron tubes. Rock or concrete-lined tunnels were used on segments from 33rd to 42nd streets under Park Avenue; 116th to 120th Streets under Broadway; 145th to Dyckman Streets (Fort George) under Broadway and St. Nicholas Avenue; and 96th Street and Broadway to Central Park North and Lenox Avenue.[87][88]

About 40% of the subway system runs on surface or elevated tracks, including steel or cast iron elevated structures, concrete viaducts, embankments, open cuts and surface routes.[92] As of 2019, there are 168 miles (270 km) of elevated tracks.[93] All of these construction methods are completely grade-separated from road and pedestrian crossings, and most crossings of two subway tracks are grade-separated with flying junctions. The sole exceptions of at-grade junctions of two lines in regular service are the 142nd Street junction,[94] the Rogers junction and the Myrtle Avenue junction, whose tracks both intersect at the same level.[95][96]

More recent projects use tunnel boring machines, which increase the cost. They minimize disruption at street level and avoid already existing utilities.[98] Examples of such projects include the extension of the IRT Flushing Line[99][100][101][102] and the IND Second Avenue Line.[103][104][105][106]

Expansion

Second Avenue Subway Community Information Center

Since the opening of the original New York City Subway line in 1904,[51][52] various official and planning agencies have proposed numerous extensions to the subway system. One of the more expansive proposals was the "IND Second System", part of a plan to construct new subway lines in addition to taking over existing subway lines and railroad rights-of-way. The most grandiose IND Second Subway plan, conceived in 1929, was to be part of the city-operated IND, and was to comprise almost 1⁄3 of the current subway system.[107][108] By 1939, with unification planned, all three systems were included within the plan, which was ultimately never carried out.[109][110] Many different plans were proposed over the years of the subway's existence, but expansion of the subway system mostly stopped during World War II.[111]

Though most of the routes proposed over the decades have never seen construction, discussion remains strong to develop some of these lines, to alleviate existing subway capacity constraints and overcrowding, the most notable being the proposals for the Second Avenue Subway. Plans for new lines date back to the early 1910s, and expansion plans have been proposed during many years of the system's existence.[107][62]

After the IND Sixth Avenue Line was completed in 1940,[112] the city went into great debt, and only 33 new stations have been added to the system since, nineteen of which were part of defunct railways that already existed. Five stations were on the abandoned New York, Westchester and Boston Railway, which was incorporated into the system in 1941 as the IRT Dyre Avenue Line.[113] Fourteen more stations were on the abandoned LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch (now the IND Rockaway Line), which opened in 1955.[114] Two stations (57th Street and Grand Street) were part of the Chrystie Street Connection, and opened in 1968;[115][116] the Harlem–148th Street terminal opened that same year in an unrelated project.[117] Six were built as part of a 1968 plan: three on the Archer Avenue Lines, opened in 1988,[118] and three on the 63rd Street Lines, opened in 1989.[119] The new South Ferry station was built and connected to the existing Whitehall Street–South Ferry station in 2009.[120] The one-stop 7 Subway Extension to the west side of Manhattan, consisting of the 34th Street–Hudson Yards station, was opened in 2015,[121][122][7] and three stations on the Second Avenue Subway in the Upper East Side were opened in the beginning of 2017.[123]

Lines and routes

A digital sign on the side of an R142 train on the 4

125th Street station on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line

| Annual passenger ridership | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Passengers | %± |

| 1901 | 253,000,000 | — |

| 1905 | 448,000,000 | +77.1% |

| 1910 | 725,000,000 | +61.8% |

| 1915 | 830,000,000 | +14.5% |

| 1920 | 1,332,000,000 | +60.5% |

| 1925 | 1,681,000,000 | +26.2% |

| 1930 | 2,049,000,000 | +21.9% |

| 1935 | 1,817,000,000 | −11.3% |

| 1940 | 1,857,000,000 | +2.2% |

| 1945 | 1,941,000,000 | +4.5% |

| 1946 | 2,067,000,000 | +6.5% |

| 1950 | 1,681,000,000 | −13.4% |

| 1955 | 1,378,000,000 | −18.0% |

| 1960 | 1,345,000,000 | −2.4% |

| 1965 | 1,363,000,000 | +1.3% |

| 1970 | 1,258,000,000 | −7.7% |

| 1975 | 1,054,000,000 | −16.2% |

| 1980 | 1,009,000,000 | −4.3% |

| 1982 | 989,000,000 | −2.0% |

| 1985 | 1,010,000,000 | +2.1% |

| 1990 | 1,028,000,000 | +1.8% |

| 1995 | 1,093,000,000 | +6.3% |

| 2000 | 1,400,000,000 | +28.1% |

| 2005 | 1,450,000,000 | +3.6% |

| 2010 | 1,605,000,000 | +10.7% |

| 2011 | 1,640,000,000 | +2.2% |

| 2012 | 1,654,000,000 | +0.1% |

| 2013 | 1,708,000,000 | +3.3% |

| 2014 | 1,751,287,621 | +2.6% |

| 2015 | 1,762,565,419 | +0.6% |

| 2016 | 1,756,814,800 | -0.3% |

| 2017 | 1,727,366,607 | -1.7% |

| 2018 | 1,680,060,402 | -2.7% |

| [124][125][126][127][128] | ||

Many rapid transit systems run relatively static routings, so that a train "line" is more or less synonymous with a train "route". In New York City, however, routings change often, for various reasons. Within the nomenclature of the subway, the "line" describes the physical railroad track or series of tracks that a train "route" uses on its way from one terminal to another. "Routes" (also called "services") are distinguished by a letter or a number and "Lines" have names. Trains display their route designation.[26]

There are 28 train services in the subway system, including three short shuttles. Each route has a color and a local or express designation representing the Manhattan trunk line of the particular service.[129][130] New York City residents seldom refer to services by color (e.g., Blue Line or Green Line) but out-of-towners and tourists often do.[26][131][132]

The 1, C, G, L, M, R, and W trains are fully local and make all stops. The 2, 3, 4, 5, A, B, D, E, F, N, and Q trains have portions of express and local service. J, Z, 6, and 7 trains vary by day or time of day. The letter S is used for three shuttle services: Franklin Avenue Shuttle, Rockaway Park Shuttle, and 42nd Street Shuttle.[130][133]

Though the subway system operates on a 24-hour basis,[26] during late night hours some of the designated routes do not run, run as a shorter route (often referred to as the 'shuttle train' version of its full-length counterpart) or run with a different stopping pattern. These are usually indicated by smaller, secondary route signage on station platforms.[130][134] Because there is no nightly system shutdown for maintenance, tracks and stations must be maintained while the system is operating. This work sometimes necessitates service changes during midday, overnight hours, and weekends.[135][136][8]

When parts of lines are temporarily shut down for construction purposes, the transit authority can substitute free shuttle buses (using MTA Regional Bus Operations bus fleet) to replace the routes that would normally run on these lines.[137] The Transit Authority announces planned service changes through its website,[138] via placards that are posted on station and interior subway-car walls,[139] and through its Twitter page.[140]

Nomenclature

| Primary Trunk line | Color[141][142] | Pantone[143] | Hexadecimal | Service bullets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IND Eighth Avenue Line | Vivid blue | PMS 286 | #2850ad | |

| IND Sixth Avenue Line | Bright orange | PMS 165 | #ff6319 | |

| IND Crosstown Line | Lime green | PMS 376 | #6cbe45 | |

| BMT Canarsie Line | Light slate gray | 50% black | #a7a9ac | |

| BMT Nassau Street Line | Terra cotta brown | PMS 154 | #996633 | |

| BMT Broadway Line | Sunflower yellow | PMS 116 | #fccc0a | |

| IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line | Tomato red | PMS 185 | #ee352e | |

| IRT Lexington Avenue Line | Apple green | PMS 355 | #00933c | |

| IRT Flushing Line | Raspberry | PMS Purple | #b933ad | |

| IND Second Avenue Line | Turquoise | PMS 638 | #00add0 | |

| Shuttles | Dark slate gray | 70% black | #808183 |

Subway map

Map of line elevation in relation to the ground; underground segments are in orange, and above ground segments are in blue, whether they are elevated, embanked, graded or open cut

Current official transit maps of the New York City Subway are based on a 1979 design by Michael Hertz Associates. The maps are not geographically accurate due to the complexity of the system (Manhattan being the smallest borough, but having the most services), but they do show major city streets as an aid to navigation. The newest edition took effect on June 27, 2010, and makes Manhattan bigger and Staten Island smaller.[133][144] Earlier diagrams of the subway (the first being produced in 1958) had the perception of being more geographically inaccurate than the diagrams today. The design of the subway map by Massimo Vignelli, published by the MTA between 1972 and 1979, has become a modern classic but the MTA deemed the map flawed due to its placement of geographical elements.[145][146]

A late night-only version of the map was introduced on January 30, 2012.[147] On September 16, 2011, the MTA introduced a Vignelli-style interactive subway map, "The Weekender",[148] to its website;[149] as the title suggests,[150] the online map provides information about any planned work, from late Friday night to early Monday morning.[151][152]

Several privately produced schematics are available online or in printed form, such as those by Hagstrom Map.[153]

Stations

7 train arriving at Vernon Boulevard – Jackson Avenue station (43s)

The long and wide mezzanine in the West Fourth Street station in Greenwich Village.

Out of the 472 stations, 470 are served 24 hours a day.[9] Underground stations in the New York City Subway are typically accessed by staircases going down from street level. Many of these staircases are painted in a common shade of green, with slight or significant variations in design.[154] Other stations have unique entrances reflective of their location or date of construction. Several station entrance stairs, for example, are built into adjacent buildings.[154] Nearly all station entrances feature color-coded globe or square lamps signifying their status as an entrance.[155]

Concourse

An entrance to the Times Square–42nd Street/Port Authority Bus Terminal station

Many stations in the subway system have mezzanines.[156] Mezzanines allow for passengers to enter from multiple locations at an intersection and proceed to the correct platform without having to cross the street before entering. Inside mezzanines are fare control areas, where passengers physically pay their fare to enter the subway system.[88][156][157] In many older stations, the fare control area is at platform level with no mezzanine crossovers.[88][158] Many elevated stations also have platform-level fare control with no common station house between directions of service.[47]

Upon entering a station, passengers may use station booths (formerly known as token booths)[159] or vending machines to buy their fare, which is currently stored in a MetroCard. Each station has at least one booth, typically located at the busiest entrance.[160] After swiping the card at a turnstile, customers enter the fare-controlled area of the station and continue to the platforms.[26] Inside fare control are "Off-Hours Waiting Areas", which consist of benches and are identified by a yellow sign.[26][161][162]

Platforms

The IND Eighth Avenue Line station at 59th Street – Columbus Circle

A typical subway station has waiting platforms ranging from 480 to 600 feet (150 to 180 m) long. Some are longer.[58][163] Platforms of former commuter rail stations—such as those on the IND Rockaway Line, are even longer. With the many different lines in the system, one platform often serves more than one service. Passengers need to look at the overhead signs to see which trains stop there and when, and at the arriving train to identify it.[26]

There are a number of common platform configurations:

On a double track line, a station may have one center island platform used for trains in both directions, or two side platforms, one for each direction.[88]

For lines with three or four tracks with express service, local stops will have side platforms and the middle one or two tracks will not stop at the station. On these lines, express stations typically have two island platforms, one for each direction. Each island platform provides a cross-platform interchange between local and express services. Some lines with four-track express service have two tracks each on two levels and use both island and side platforms.[26][88]

Accessibility

Street elevator serving as an entrance to the 66th Street–Lincoln Center station

Since the majority of the system was built before 1990, the year the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) went into effect, many New York City Subway stations were not designed to be handicapped-accessible.[164] Since then, elevators have been built in newly constructed stations to comply with the ADA. (Most grade-level stations required little modification to meet ADA standards.) In addition, the MTA identified "key stations", high-traffic and/or geographically important stations, which must conform to the ADA when they are extensively renovated. As of January 2017, there are 120 currently accessible stations; many of them have AutoGate access.[26][165] Under the current MTA plans, the number of ADA accessible stations will go up to 144 by 2020.[166]

In June 2016, the MTA was sued by a disability rights group for not including an elevator during the $21 million renovation of the Middletown Road subway station in the Bronx. Only 19% of all of the subway system's stations were fully accessible to people with disabilities at the time,[167] a number that rose to 24% the next year.[168] In April 2017, two simultaneous lawsuits against the MTA, one in state court and one in federal court, claimed that the system was breaking one of the city's human-rights laws by violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. As a result, the suits said, the MTA failed to "eliminate and prevent discrimination from playing any role in actions relating to employment, public accommodations and housing and other real estate."[168]

Rolling stock

A train of R32 cars on the A train

Interior of an R142A car on the 4 train

Interior of an R62 car on the 3 train

Driver's cab of an R160B subway car on the N train

The system maintains two separate fleets of cars, one for the A Division routes and another for the B Division routes.[171] All B Division equipment is about 10 feet (3.05 m) wide and either 60 feet 6 inches (18.44 m) or 75 feet (22.86 m) long, whereas A Division equipment is approximately 8 feet 9 inches (2.67 m) wide and 51 feet 4 inches (15.65 m) long.[172] A portion of the 60-foot B Division fleet is used for operation in the BMT Eastern Division, where 75-foot (22.86 m) long cars are not permitted.[173][174]

Cars purchased by the City of New York since the inception of the IND and the other divisions beginning in 1948 are identified by the letter "R" followed by a number; e.g.: R32.[171] This number is the contract number under which the cars were purchased.[175] Cars with nearby contract numbers (e.g.: R1 through R9, or R26 through R29, or R143 through R179) may be relatively identical, despite being purchased under different contracts and possibly built by different manufacturers.[176]

Since 1999, the R142, R142A, R143, R160, R179 and R188 cars have been placed into service.[177][178] These cars are collectively known as New Technology Trains (NTTs) due to modern innovations such as LED and LCD route signs and information screens, as well as recorded train announcements and the ability to facilitate Communication-Based Train Control (CBTC).[178][179]

As part of the 2017–2020 MTA Financial Plan, 600 subway cars will have electronic display signs installed to improve customer experience.[180]

Fares

Riders pay a single fare to enter the subway system and may transfer between trains at no extra cost until they exit via station turnstiles; the fare is a flat rate regardless of how far or how long the rider travels. Thus, riders must swipe their MetroCard upon entering the subway system, but not a second time upon leaving.[181]

As of April 2016, nearly all fares are paid by MetroCard;[182] the base fare is $2.75 when purchased in the form of a reusable "pay per ride" MetroCard,[181] with the last fare increase occurring on March 22, 2015.[183] Single-use cards may be purchased for $3.00, and 7-day and 30-day unlimited ride cards can lower the effective per-ride fare significantly.[184] Reduced fares are available for the elderly and people with disabilities.[26][185]

Fares were stored in a money room at 370 Jay Street in Downtown Brooklyn starting in 1951, when the building opened as a headquarters for the New York City Board of Transportation.[186] The building is close to the lines of all three subway divisions (the IRT, BMT, and IND) and thus was a convenient location to collect fares, including tokens and cash, via money trains. Passageways from the subway stations, including a visible door in the Jay Street IND station, lead to a money sorting room in the basement of the building.[187][188] The money trains were replaced by armored trucks in 2006.[187][188][189]

MetroCard

The current MetroCard design

In November 1993,[190] a fare system called the MetroCard was introduced, which allows riders to use cards that store the value equal to the amount paid to a subway station booth clerk or vending machine.[191] The MetroCard was enhanced in 1997 to allow passengers to make free transfers between subways and buses within two hours; several MetroCard-only transfers between subway stations were added in 2001.[192][193] With the addition of unlimited-ride MetroCards in 1998, the New York City Transit system was the last major transit system in the United States with the exception of BART in San Francisco to introduce passes for unlimited bus and rapid transit travel.[194] Unlimited-ride MetroCards are available for 7-day and 30-day periods.[195] One-day "Fun Pass" and 14-day cards were also introduced, but have since been discontinued.[196]

MetroCard replacement

On October 23, 2017, it was announced that the MetroCard would be phased out and replaced by OMNY, a contactless fare payment system also by Cubic, with fare payment being made using Apple Pay, Google Pay, debit/credit cards with near-field communication technology, or radio-frequency identification cards.[197][198] All buses and subway stations will be compatible with electronic fare collection by 2020. However, support of the MetroCard is slated to remain until 2023.[198]

Modernization

A subway station rebuilt under the Enhanced Station Initiative

Since the late 20th century, the MTA has started several projects to maintain and improve the subway. In the 1990s, it started converting the BMT Canarsie Line to use communications-based train control, utilizing a moving block signal system that allowed more trains to use the tracks and thus increasing passenger capacity.[199] After the Canarsie Line tests were successful, the MTA expanded the automation program in the 2000s and 2010s to include other lines.[200][201] As part of another program called FASTRACK, the MTA started closing sections of lines during weekday nights in 2012, in order to allow workers to clean these lines without being hindered by train movements.[202] It expanded the program beyond Manhattan the next year after noticing how efficient the FASTRACK program was compared to previous service diversions.[203] In 2015, the MTA announced a wide-ranging improvement program as part of the 2015–2019 Capital Program. Thirty stations would be extensively rebuilt under the Enhanced Station Initiative, and new R211 subway cars would be able to fit more passengers.[204][205]

The MTA has also started some projects to improve passenger amenities. It added train arrival "countdown clocks" to most A Division stations (except on the IRT Flushing Line, serving the 7 and <7> trains) and the BMT Canarsie Line (L train) by late 2011, allowing passengers on these routes to see train arrival times using real-time data.[206] A similar countdown-clock project for the B Division and the Flushing Line was deferred[207] until 2016, when a new Bluetooth-based clock system was tested successfully.[208] Beginning in 2011, the MTA also started "Help Point" to aid with emergency calls or station agent assistance.[209] The Help Point project was deemed successful, and the MTA subsequently installed Help Points in all stations.[210] Interactive touchscreen "On The Go! Travel Station" kiosks, which give station advisories, itineraries, and timetables, were installed starting in 2011,[211] with the program also being expanded after a successful pilot.[212] Cellular phone and wireless data in stations, first installed in 2011 as part of yet another pilot program,[213] was also expanded systemwide due to positive passenger feedback.[210] Finally, credit-card trials at several subway stations in 2006 and 2010[214][215] led to proposals for contactless payment to replace the aging MetroCard.[216]

Safety and security

Signaling

Wayside block signaling

Example of a wayside block signal at the 34th Street–Hudson Yards station

The system currently uses automatic block signaling with fixed wayside signals and automatic train stops in order to provide safe train operation across the whole system.[218] The New York City Subway system has, for the most part, used block signalling since its first line opened, and many portions of the current signaling system were installed between the 1930s and 1960s. These signals work by preventing trains from entering a "block" occupied by another train. Typically, the blocks are 1,000 feet (300 m) long.[219] Red and green lights show whether a block is occupied or vacant. The train's maximum speed will depend on how many blocks are open in front of it. The signals do not register a train's speed, nor where in the block the train is located.[220][221]

Communications-based train control

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the MTA began automating the subway by installing CBTC, which supplements rather than replaces the fixed-block signal system; it allows trains to operate more closely together with lower headways. The BMT Canarsie Line, on which the L train runs, was chosen for pilot testing because it is a self-contained line that does not operate in conjunction with other lines. CBTC became operational in February 2009.[223] Due to an unexpected ridership increase, the MTA ordered additional cars, and increased service from 15 trains to 26 trains per hour, an achievement beyond the capability of the block system.[224] The total cost of the project was $340 million.[219]

By 2018, CBTC was in the process of being installed on several other routes as well, particularly the IND Queens Boulevard Line (E, F,

The New York City Subway uses a system known as Automatic Train Supervision (ATS) for dispatching and train routing on the A Division[231] (the Flushing line and the trains used on the 7 and <7> services do not have ATS.)[231] ATS allows dispatchers in the Operations Control Center (OCC) to see where trains are in real time, and whether each individual train is running early or late.[231] Dispatchers can hold trains for connections, re-route trains, or short-turn trains to provide better service when a disruption causes delays.[231]

Train accidents

Despite the signal system, there have been at least 64 major train accidents since 1918, when a train bound for South Ferry smashed into two trains halted near Jackson Avenue on the IRT White Plains Road Line in the Bronx.[232] Several accidents resulted when the train operator ran through red signals and rear-ended the subway train in front of it; this resulted from the signaling practice of "keying by", which allowed train operators to bypass red signals. The deadliest accident, the Malbone Street Wreck, occurred on November 1, 1918 beneath the intersection of Flatbush Avenue, Ocean Avenue, and Malbone Street (the latter of which is now Empire Boulevard) near the Prospect Park station of the then-BRT Brighton Line in Brooklyn, killing 93 people.[233] As a result of accidents, especially more recent ones such as the 1995 Williamsburg Bridge crash, timer signals were installed. These signals have resulted in reduced speeds across the system. Accidents such as derailments are also due to broken equipment, such as the rails and the train itself.[232]

Passenger safety

Track safety and suicides

A portion of subway-related deaths in New York consists of suicides committed by jumping in front of an oncoming train. Between 1990 and 2003, 343 subway-related suicides have been registered out of a citywide total of 7,394 (4.6%) and subway-related suicides increased by 30%, despite a decline in overall suicide numbers.[234]

Due to increase in people hit by trains in 2013,[235] in late 2013 and early 2014 the MTA started a test program at one undisclosed station, with four systems and strategies to eliminate the number of people hit by trains. Closed-circuit television cameras, a web of laser beams stretched across the tracks, radio frequencies transmitted across the tracks, and thermal imaging cameras focused on the station's tracks were set to be installed at that station.[236] At the unidentified station, tests have gone so well at the testing site that these track protection systems will be installed systemwide as part of the 2015–2019 capital program.[237]

The MTA also expressed interest in starting a pilot program to install platform edge doors.[238] Several planned stations in the New York City Subway may possibly feature platform screen doors, possibly including future stations such as those part of the Second Avenue Subway.[239] Currently, the MTA is planning a test program to install screen doors at a subway station on the BMT Canarsie Line. As part of the 2010–2014 capital program, the station was going to be Sixth Avenue, but it is uncertain whether or not that this will be the station chosen.[240] Following a series of incidents during one week in November 2016, in which three people were injured or killed after being pushed onto the tracks, the MTA started to consider installing platform edge doors for the 42nd Street Shuttle.[241] Numerous challenges come with platform doors. Some subway lines operate multiple subway car models, and their doors often do not line up.[242] Many platforms are not strong enough to hold the additional weight of a platform barrier, thus requiring extensive renovations if they were to be installed.[242]

Crime

Crime rates have varied, but there has been a downward trend starting in the 1990s and continuing today.[243] In order to fight crime, various approaches have been used over the years, including an "If You See Something, Say Something" campaign[244] and, starting in 2016, banning people who commit a crime in the subway system from entering the system for a certain length of time.[245]

In July 1985, the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City published a study showing riders abandoning the subway, fearing the frequent robberies and generally bad circumstances.[246]

To counter these developments, policy that was rooted in the late 1980s and early 1990s was implemented.[247][248] In line with this Fixing Broken Windows philosophy, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) began a five-year program to eradicate graffiti from subway trains in 1984.[249] In 1993, Mayor Rudy Giuliani took office and with Police Commissioner Howard Safir, the strategy was more widely deployed in New York. Crime rates in the subway and city dropped.[250] Giuliani's campaign credited the success to his policy.[251] The extent to which his policies deserve the credit is disputed.[252]

New York City Police Department Commissioner William J. Bratton and author of Fixing Broken Windows, George L. Kelling, however, stated the police played an "important, even central, role" in the declining crime rates.[246] The trend continued and Giuliani's successor, Michael Bloomberg, stated in a November 2004 press release: "Today, the subway system is safer than it has been at any time since we started tabulating subway crime statistics nearly 40 years ago."[253]

Photography

After the September 11, 2001, attacks, the MTA exercised extreme caution regarding anyone taking photographs or recording video inside the system and proposed banning all photography and recording in a meeting around June 2004.[254] However, due to strong response from both the public and from civil rights groups, the rule of conduct was dropped. In November 2004, the MTA again put this rule up for approval, but was again denied,[255] though many police officers and transit workers still confront or harass people taking photographs or videos.[256] However, on April 3, 2009, the NYPD issued a directive to officers stating that it is legal to take pictures within the subway system so long as it is not accompanied with suspicious activity.[257]

Currently, the MTA Rules of Conduct, Restricted Areas and Activities section states that anyone may take pictures or record videos, provided that they do not use any of three tools: lights, reflectors, or tripods. These three tools are permitted only by members of the press who have identification issued by the NYPD.[258]

Terrorism prevention

On July 22, 2005, in response to bombings in London, the New York City Transit Police introduced a new policy of randomly searching passengers' bags as they approached turnstiles. The NYPD claimed that no form of racial profiling would be conducted when these searches actually took place. The NYPD has come under fire from some groups that claim purely random searches without any form of threat assessment would be ineffectual. Donna Lieberman, Executive Director of the NYCLU, stated, "This NYPD bag search policy is unprecedented, unlawful and ineffective. It is essential that police be aggressive in maintaining security in public transportation. But our very real concerns about terrorism do not justify the NYPD subjecting millions of innocent people to suspicionless searches in a way that does not identify any person seeking to engage in terrorist activity and is unlikely to have any meaningful deterrent effect on terrorist activity."[259] The searches were upheld by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in MacWade v. Kelly.[260]

On April 11, 2008, MTA received a Ferrara Fire Apparatus Hazardous Materials Response Truck, which went into service three days later. It will be used in the case of a chemical or bioterrorist attack.[261]

Challenges

2009–2010 budget cuts

28th Street station after the W train was discontinued in mid-2010. Note the dark grey tape masked over the W bullet. (This sign has since been replaced due to the restoration of the W in 2016.)

The MTA faced a budget deficit of US$1.2 billion in 2009.[264] This resulted in fare increases (three times from 2008 to 2010)[265] and service reductions (including the elimination of two part-time subway services, the V and W). Several other routes were modified as a result of the deficit. The N was made a full-time local in Manhattan (in contrast to being a weekend local/weekday express before 2010), while the Q was extended nine stations north to Astoria–Ditmars Boulevard on weekdays, both to cover the discontinued W. The M was combined with the V, routing it over the Chrystie Street Connection, IND Sixth Avenue Line and IND Queens Boulevard Line to Forest Hills–71st Avenue on weekdays instead of via the BMT Fourth Avenue Line and BMT West End Line to Bay Parkway. The G was truncated to Court Square full-time. Construction headways on eleven routes were lengthened, and off-peak service on seven routes were lengthened.[266]

2017 state of emergency

In June 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order declaring a state of emergency for the New York City Subway[267] after a series of derailments,[268][269] track fires,[270][271] and overcrowding incidents.[270][272] On June 27, 2017, thirty-nine people were injured when an A train derailed at 125th Street,[273][274] damaging tracks and signals[268] then catching on fire.[275][268] On July 21, 2017, the second set of wheels on a southbound Q train jumped the track near Brighton Beach, with nine people suffering injuries[269] due to improper maintenance of the car in question.[276][277] To solve the system's problems, the MTA officially announced the Genius Transit Challenge on June 28, where contestants could submit ideas to improve signals, communications infrastructure, or rolling stock.[278][279]

On July 25, 2017, Chairman Joe Lhota announced a two-phase, $9 billion New York City Subway Action Plan to stabilize the subway system and to prevent the continuing decline of the system.[280][281][282][283] The first phase, costing $836 million, consisted of five categories of improvements in Signal and Track Maintenance, Car Reliability, System Safety and Cleanliness, Customer Communication, and Critical Management Group. The $8 billion second phase would implement the winning proposals from the Genius Transit Challenge and fix more widespread problems.[281][282][283] Six winning submissions for the Genius Transit Challenge were announced in March 2018.[284]

In October 2017, city comptroller Scott Stringer released an analysis that subway delays could cost up to $389 million or $243.1 million or $170.2 million per year depending on how long were the delays.[285]

In November 2017, The New York Times published its investigation into the crisis. It found that the crisis had arisen as a result of financially unsound decisions by local and state politicians from both the Democratic and Republican parties. According to the Times, these decisions included overspending; overpaying unions and interest groups; advertising superficial improvement projects while ignoring more important infrastructure; and agreeing to high-interest loans that would have been unnecessary without these politicians' other interventions. By this time, the subway's 65% average on-time performance was the lowest among all major cities' transit systems, and every non-shuttle subway route's on-time performance had declined in the previous ten years.[286]

Capacity constraints

The interior of a Q train during afternoon rush hour

Several subway lines have reached their operational limits in terms of train frequency and passengers, according to data released by the Transit Authority. As of June 2007, all of the A Division services except the 42nd Street Shuttle, as well as the E and L trains, were beyond capacity, as well as portions of the N train.[287][288] In April 2013, New York magazine reported that the system was more crowded than it had been in the previous 66 years.[289] The subway reached a daily ridership of 6 million for 29 days in 2014, and was expected to record a similar ridership level for 55 days in 2015; by comparison, in 2013, daily ridership never reached 6 million.[290] In particular, the express tracks of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line and IND Queens Boulevard Line are noted for operating at full capacity during peak hours.[287][291] The Long Island Rail Road East Side Access project is expected to bring many more commuters to the Lexington Avenue Line when it opens around the year 2022, further overwhelming its capacity.[292][293][294]

By early 2016, delays as a result of overcrowding were up to more than 20,000 every month, four times the amount in 2012. The overcrowded trains have resulted in an increase of assaults because of tense commuters. With less platform space, more passengers are forced to be on the edge of the platform resulting in the increased possibility of passengers falling on the track. One possible solution that the MTA is considering is platform screen doors, which exist on the AirTrain JFK to prevent passengers from falling onto the tracks. In order to prevent hitting passengers who could fall onto the tracks, train operators are being instructed to go into stations at lower speeds. The increased proximity of riders could result in the spread of contagious diseases.[295]

Expanding service frequency via CBTC

The Second Avenue Subway, which has provisions for communications-based train control (CBTC), was built to relieve pressure on the Lexington Avenue Line (4, 5, 6, and <6> trains) by shifting an estimated 225,000 passengers.[296] In addition, CBTC installation on the Flushing Line is expected to increase the rate of trains per hour on the 7 and <7> trains, but little relief will come to other crowded lines until later. CBTC on the Flushing Line is expected to be completed in September 2017.[180] The L train, which is overcrowded during rush hours, already has CBTC operation.[297] The installation of CBTC has reduced the L's running time by 3%.[296] Even with CBTC, there are limits on the potential increased service. For L service to be increased further, a power upgrade as well as additional space for the L to turn around at its Manhattan terminus, Eighth Avenue, are needed.[136]

The MTA is also seeking to implement CBTC on the IND Queens Boulevard Line. CBTC is to be installed on this line in five phases, with phase one (50th Street/8th Avenue and 47th–50th Streets–Rockefeller Center to Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike) being included in the 2010–2014 capital budget. The $205.8 million contract for the installment of phase one was awarded in 2015 to Siemens and Thales. Planning for phase one started in 2015, with major engineering work to follow in 2017.[291][298] The total cost for the entire Queens Boulevard Line is estimated at over $900 million.[299] The Queens Boulevard CBTC project is expected to be completed in 2021.[180] Funding for CBTC on the IND Eighth Avenue Line is also provided in the 2015–2019 capital project.[300] The MTA projects that 355 miles of track will receive CBTC signals by 2029, including most of the IND, as well as the IRT Lexington Avenue Line and the BMT Broadway Line.[301] The MTA also is planning to install CBTC equipment on the IND Crosstown Line, the BMT Fourth Avenue Line and the BMT Brighton Line before 2025.[302] As part of the installation of CBTC, the whole fleet of subway cars needs to be remodeled or replaced.[296]

Service frequency and car capacity

Mockup of the proposed experimental open-gangway configuration for the R211T subway car

Due to an increase of ridership, the MTA has tried to increase capacity wherever possible by adding more frequent service, specifically during the evening hours. However, this increase will not likely keep up with the growth of subway ridership.[295][303][304] Some lines have capacity for additional trains during peak times, but there are too few subway cars for this additional service to be operated.[136]

Platform crowd control

The MTA is also testing smaller ideas on some services. Starting in late 2015, 100 "station platform controllers" were deployed for the F, 6, and 7 trains, to manage the flow of passengers on and off crowded trains during morning rush hours. There were a total of 129 such employees, who also answer passengers' questions about subway directions, rather than having conductors answer them and thus delaying the trains.[308][309][310][311] In early 2017, the test was expanded to the afternoon peak period with an increase of 35 platform conductors.[180][312] In November of the same year, 140 platform controllers and 90 conductors gained iPhone 6S devices so they could receive notifications of, and tell riders about, subway disruptions.[313] Subway guards, the predecessors to the platform controllers, were first used during the Great Depression and World War II.[295]

Shortened "next stop" announcements on trains were being tested on the 2 and 5 trains. "Step aside" signs on the platforms, reminding boarding passengers to let departing passengers off the train first, are being tested at Grand Central–42nd Street, 51st Street, and 86th Street on the Lexington Avenue Line.[311][314] Cameras would also be installed so the MTA could observe passenger overcrowding.[296][315][316][317]

In systems like the London Underground, stations are simply closed off when they are overcrowded, such as the busy Oxford Circus tube station, which had to close more than 100 times in a year. That type of restriction is not necessary yet on the New York City Subway, according to MTA spokesman Kevin Ortiz.[295]

Subway flooding

Rain from drainage pipes comes into a subway car

Service on the subway system is occasionally disrupted by flooding from rainstorms, even minor ones.[318] Rainwater can disrupt signals underground and require the electrified third rail to be shut off. Every day, the MTA moves 13 million gallons of water when it is not raining.[319] Since 1992, $357 million has been used to improve 269 pump rooms. By August 2007, $115 million was earmarked to upgrade the remaining 18 pump rooms.[320]

Despite these improvements, the transit system continues to experience flooding problems. On August 8, 2007, after more than 3 inches (76 mm) of rain fell within an hour, the subway system flooded, causing almost every subway service to either be disabled or seriously disrupted, effectively halting the morning rush.[321][322] This was the third incident in 2007 in which rain disrupted service. The system was disrupted on this occasion because the pumps and drainage system can handle only a rainfall rate of 1.75 inches (44 mm) per hour; the incident's severity was aggravated by the scant warning as to the severity of the storm.[319][323] []

In addition, as part of a $130 million and an estimated 18-month project, the MTA began installing new subway grates in September 2008 in an attempt to prevent rain from overflowing into the subway system. The metallic structures, designed with the help of architectural firms and meant as a piece of public art, are placed atop existing grates but with a 3-to-4-inch (76 to 102 mm) sleeve to prevent debris and rain from flooding the subway. The racks will at first be installed in the three most flood-prone areas as determined by hydrologists: Jamaica, Tribeca, and the Upper West Side. Each neighborhood has its own distinct design, some featuring a wave-like deck which increases in height and features seating (as in Jamaica), others with a flatter deck that includes seating and a bike rack.[324][325][326]

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused significant damage to New York City, and many subway tunnels were inundated with floodwater. The subway opened with limited service two days after the storm and was running at 80 percent capacity within five days; however, some infrastructure needed years to repair. A year after the storm, MTA spokesperson Kevin Ortiz said, "This was unprecedented in terms of the amount of damage that we were seeing throughout the system."[327][328] The storm flooded nine of the system's 14 underwater tunnels, many subway lines, and several subway yards, as well as completely destroying a portion of the IND Rockaway Line and much of the South Ferry terminal station. Reconstruction required many weekend closures on several lines as well as the 53rd Street Tunnel, Clark Street Tunnel, Cranberry Street Tunnel, Joralemon Street Tunnel and Steinway Tunnel; several long-term closures were also included on the Greenpoint Tunnel, Montague Street Tunnel, Rockaway Line, and the South Ferry station, with a partial closure planned for the 14th Street Tunnel; some reconstruction is expected to last until at least 2020.[329]

Full and partial subway closures

On October 29, 2012, another full closure was ordered before the arrival of Hurricane Sandy.[328] All services on the subway, the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North were gradually shut down that day at 7:00 P.M., to protect passengers, employees and equipment from the coming storm.[333] The storm caused serious damage to the system, especially the IND Rockaway Line, upon which many sections between Howard Beach–JFK Airport and Hammels Wye on the Rockaway Peninsula were heavily damaged, leaving it essentially isolated from the rest of the system.[334][335] This required the NYCTA to truck in 20 R32 subway cars to the line to provide some interim service (temporarily designated the H).[336][337][338] Also, several of the system's tunnels under the East River were flooded by the storm surge.[339] South Ferry suffered serious water damage and did not reopen until April 4, 2013 by restoring service to the older loop-configured station that had been replaced in 2009;[340][341] the stub-end terminal tracks remained out of service until June 2017.[342][343][344][345]

Since 2015, there have been three blizzard-related subway shutdowns. On January 26, 2015, another full closure was ordered by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo due to the January 2015 nor'easter, which was originally projected to leave New York City with 20 to 30 inches (51 to 76 cm) of snow.[346] The next day, the subway system was partially reopened.[347][348] A number of New York City residents criticized Cuomo's decision to shut down the subway system for the first time ever due to snow. The nor'easter dropped much less snow in the city than originally expected, totaling only 9.8 inches (25 cm) in Central Park.[349][350] On January 23, 2016, a partial subway closure was ordered due to the January 2016 United States blizzard, wherein all aboveground stations were closed; the underground lines remained open during the blizzard.[351][352] Most of the subway resumed service the next day, with some lingering delays due to an average of 26 inches (66 cm) of snow in the area.[353] On March 13, 2017, another partial subway closure of all aboveground stations was ordered for the next day due to the March 2017 nor'easter, which was forecast to bring up to 20 inches (51 cm) of snow to the area.[354]

Litter and rodents

Litter accumulation in the subway system is perennial. In the 1970s and 1980s, dirty trains and platforms, as well as graffiti were a serious problem. The situation had improved since then, but the 2010 budget crisis, which caused over 100 of the cleaning staff to lose their jobs, threatened to curtail trash removal.[355][356] Every day, the MTA removes 40 tons of trash from 3,500 trash receptacles.[357]

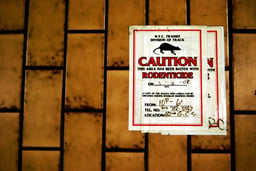

The New York City Subway system is infested with rats.[358] Rats are sometimes seen on platforms,[359] and are commonly seen foraging through garbage thrown onto the tracks. They are believed to pose a health hazard, and on rare instances have been known to bite humans.[360] Subway stations notorious for rat infestation include Chambers Street, Jay Street–MetroTech, West Fourth Street, Spring Street and 145th Street.[361]

Decades of efforts to eradicate or simply thin the rat population in the system have been unsuccessful. In March 2009, the Transit Authority announced a series of changes to its vermin control strategy, including new poison formulas and experimental trap designs.[362] In October 2011, they announced a new initiative to clean 25 subway stations, along with their garbage rooms, of rat infestations.[363] That same month, the MTA announced a pilot program aimed at reducing levels of garbage in the subways by removing all garbage bins from the subway platforms. The initiative was tested at the Eighth Street–New York University and Flushing–Main Street stations.[364] As of March 2016, stations along the BMT Jamaica Line, BMT Myrtle Avenue Line, and various other stations had their garbage cans removed due to the success of the program.[365] In March 2017 the program was ended as a failure.[366]

The old vacuum trains that are designed to remove trash from the tracks are ineffective and often broken.[365] A 2016 study by Travel Math had the New York City Subway listed as the dirtiest subway system in the country based on the number of viable bacteria cells.[367] In August 2016, the MTA announced that it had initiated Operation Track Sweep, an aggressive plan to dramatically reduce the amount of trash on the tracks and in the subway environment. This was expected to reduce track fires and train delays. As part of the plan, the frequency of station track cleaning would be increased, and 94 stations would be cleaned per two-week period, an increase from the previous rate of 34 stations every two weeks.[357] The MTA launched an intensive two-week, system-wide cleaning on September 12, 2016.[368] Three new powerful vacuum trains were later ordered; one arrived in 2018, and the others are expected in 2019.[369] The operation will also include 27 new refuse cars [370]

On March 28, 2017, the New York State Comptroller, Thomas DiNapoli, announced the MTA's pilot program to remove trash cans had been scrapped. His office had criticized the agency for the program.[357]

Noise

Rolling stock on the New York City Subway produces high levels of noise that exceed guidelines set by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.[371] In 2006, Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health found noise levels averaged 95 decibel (dB) inside subway cars and 94 dB on platforms.[371] Daily exposure to noise at such levels for as little as 30 minutes can lead to hearing loss.[371] Noise on one in 10 platforms exceeded 100 dB.[371] Under WHO and EPA guidelines, noise exposure at that level is limited to 1.5 minutes.[371] A subsequent study by Columbia and the University of Washington found higher average noise levels in the subway (80.4 dB) than on commuter trains including Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) (79.4 dB), Metro-North (75.1 dB) and Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) (74.9 dB).[372] Since the decibel scale is a logarithmic scale, sound at 95 dB is 10 times more intense than at 85 dB, 100 times more intense than at 75 dB, and so forth.[372] In the second study, peak subway noise registered at 102.1 dB.[372]

For the construction of the Second Avenue Subway, the MTA, with the engineering firm Arup, worked to reduce the noise levels in stations. In order to reduce noise for all future stations starting with the Second Avenue Subway, the MTA is investing in low-vibration track using ties encased in concrete-covered rubber and neoprene pads. Continuously welded rail, which is also being installed, reduces the noise being made by the wheels of trains. The biggest change that is going to be made is in the design of stations. Current stations were built with tile and stone, which bounce sound everywhere, while newer stations will have the ceilings lined with absorbent fiberglass or mineral wool that will direct sound toward the train and not the platform. With less noise from the trains, platform announcements could be heard more clearly. They will be clearer with speakers spaced periodically on the platform, angled so that announcements can be heard by the riders. The Second Avenue Subway has the first stations to test this technology.[373]

Public relations

The New York City Board of Transportation, and its successor, MTA New York City Transit, has had numerous events that promote increased ridership of their transit system.

Miss Subways

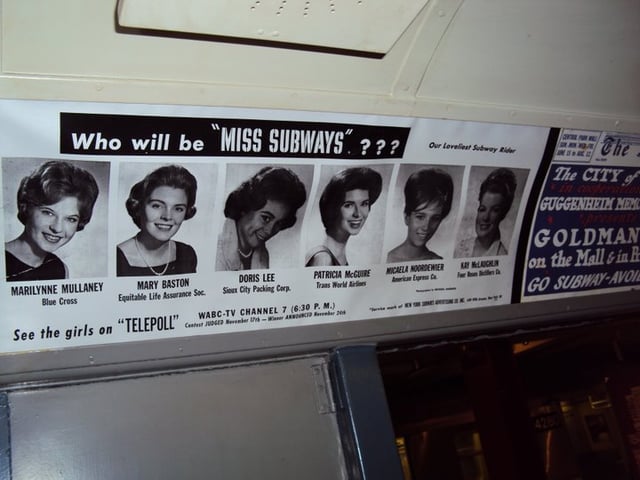

An advertisement for Miss Subways at the New York Transit Museum

From 1941 to 1976, the Board of Transportation/New York City Transit Authority sponsored the "Miss Subways" publicity campaign.[374] In the musical On the Town, the character Miss Turnstiles is based on the Miss Subways campaign.[375][376] The campaign was resurrected in 2004, for one year, as "Ms. Subways". It was part of the 100th anniversary celebrations. The monthly campaign, which included the winners' photos and biographical blurbs on placards in subway cards, featured such winners as Mona Freeman and prominent New York City restaurateur Ellen Goodman. The winner of this contest was Caroline Sanchez-Bernat, an actress from Morningside Heights.[377]

Subway Series

An R142 subway train in a special livery for the 2000 Subway Series

Subway Series is a term applied to any series of baseball games between New York City teams, as opposing teams can travel to compete merely by using the subway system. Subway Series is a term long used in New York, going back to series between the Brooklyn Dodgers or New York Giants and the New York Yankees in the 1940s and 1950s. Today, the term is used to describe the rivalry between the Yankees and the New York Mets. During the 2000 World Series, cars on the 4 train (which stopped at Yankee Stadium) were painted with Yankee colors, while cars on the 7 train (which stopped at Shea Stadium) had Mets colors.[378] The term could also be applied to the rivalry between the New York Knicks and the Brooklyn Nets of the National Basketball Association, or the New York Rangers and the New York Islanders of the National Hockey League ever since the Nets and the Islanders moved to the Barclays Center in Brooklyn.[379][380]

Holiday Train

Nostalgia Train at Second Avenue station in 2016

Since 2003, the MTA has operated a Holiday Train on Sundays in November and December, from the first Sunday after Thanksgiving to the Sunday before Christmas Day.[381] This train was made of cars from the R1 through R9 series, which have been preserved by Railway Preservation Corp. and the New York Transit Museum. The route made all stops between Second Avenue in Manhattan and Queens Plaza in Queens via the IND Sixth Avenue Line and the IND Queens Boulevard Line. In 2011, the train operated on Saturdays instead of Sundays.[382] In 2017, the train ran between Second Avenue and 96th Street.[383]

The contract, car numbers (and year built) used were Arnines, specifically R1 100 (built 1930), R1 381 (1931), R4 401 (1932), R4 484 (1932) – Bulls Eye lighting and a test P.A. system added in 1946, R6-3 1000 (1935), R6-1 1300 (1937), R7A 1575 (1938) – rebuilt in 1947 as a prototype for the R10 subway car, and R9 1802 (1940).[384]

Full train wraps

Since 2008, the MTA has tested full train wraps on 42nd Street Shuttle rolling stock. In full train wraps, advertising entirely covers the interiors and exteriors of the train, as opposed to other routes, whose stock generally only displays advertising on placards inside the train.[385][386] While most advertisements are well received, a few advertisements have been controversial. Among the more contentious wraps that were withdrawn are a 2015 ad for the TV show The Man in the High Castle, which featured a Nazi flag,[387][388] and an ad for Fox Sports 1, in which a shuttle train and half of its seats were plastered with negative quotes about the New York Knicks, one of the city's NBA teams.[389][390]

Other routes have seen limited implementation of full train wraps. For instance, in 2010, one R142A train set on the 6 route was wrapped with a Target advertisement.[391] In 2014, the Jaguar F-Type was advertised on train sets running on the F route.[392][393] Some of these wraps have also been controversial, such as a Lane Bryant wrap in 2015 that displayed lingerie models on the exteriors of train cars.[394]

LGBT Pride-themed trains and MetroCards

See also

List of metro systems

List of United States rapid transit systems by ridership

Graffiti in New York

Staten Island Railway

Subway Challenge

New York City Subway in popular culture

Transportation in New York City