Muscogee (Creek) Nation

_Nation-RGitU5WxgTZn6tc7K6jjJb9otxriEJ)

Muscogee (Creek) Nation

_Nation-RGitU5WxgTZn6tc7K6jjJb9otxriEJ)

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80,591[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Muscogee"Creek (Mvskoke)"[36] , Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed Dec. 22, 2009 Four Mothers Society, Green Corn Ceremony (Posketv) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Muscogee people, Alabama, Hitchiti, Koasati, Natchez Nation, Shawnee, Seminole, and Yuchi |

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Creek Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati, with Muscogee retaining the largest number of speakers. They commonly refer to themselves as Este Mvskokvlke (pronounced [isti məskógəlgi]). Historically, they were often referred to as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast.[2]

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation is the largest of the federally recognized Muscogee tribes. The Muskogean-speaking Alabama, Koasati, Hitchiti, and Natchez people, as well as Algonquian-speaking Shawnee[3] and Yuchi (language isolate) are enrolled in the Muscogee Creek Nation. Historically, the latter two groups were from different language families than the Muscogee. Other federally recognized Muscogee groups include the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, Kialegee Tribal Town, and Thlopthlocco Tribal Town of Oklahoma, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, and the Poarch Band of Creeks in Alabama.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80,591[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Muscogee"Creek (Mvskoke)"[36] , Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed Dec. 22, 2009 Four Mothers Society, Green Corn Ceremony (Posketv) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Muscogee people, Alabama, Hitchiti, Koasati, Natchez Nation, Shawnee, Seminole, and Yuchi |

Jurisdiction

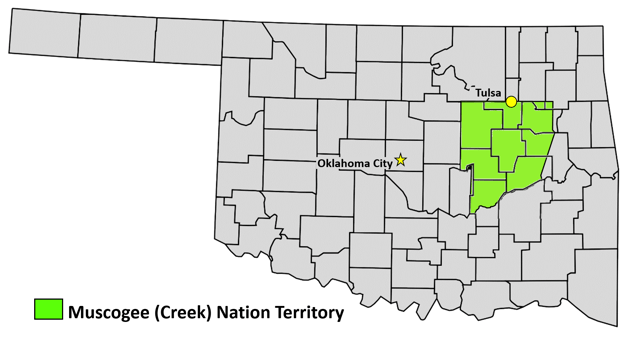

Muscogee (Creek) Nation Territory

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation is headquartered in Okmulgee, Oklahoma and serves as the seat of tribal government. The Muscogee Nation Reservation status was reaffirmed in 2017 by decision of Tenth Circuit Court in Murphy v. Royal which held that the allotted Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation in Oklahoma has not been disestablished and therefore retains jurisdiction over tribal citizens in Creek, Hughes, Okfuskee, Okmulgee, McIntosh, Muskogee, Tulsa, and Wagoner counties in Oklahoma.[1]

The decision in Murphy v. Royal was appealed to the United States Supreme Court on February 6, 2018 and certiorari was granted on May 21, 2018.[4] (See also: Carpenter v. Murphy.)

Government

Muscogee (Creek) Nation Mound building. Seat of government for both Legislative and Judicial branches of government

Opothle Yahola: Muscogee (Creek) Chief circa 1800's

The government of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. Okmulgee is the capital of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and also serves as the seat of government.[5]

Executive branch

The Executive branch is led by a Principal Chief, Second Chief, Tribal Administrator, and Secretary of the Nation. The Principal Chief and Second Chief are democratically elected every four years. Citizens cast ballots for both the Principal Chief and Second Chief as they are elected individually. The Principal Chief then chooses staff; some of which must be confirmed by the legislative branch known as The National Council. The current members of the executive branch are as follows:

James Floyd, Principal Chief

Louis Hicks, Second Chief

Legislative branch

The legislative branch is the National Council and consists of 16 members elected to represent the 8 different districts within the tribe's jurisdictional area. National Council representatives draft and sponsor the laws and resolutions of the Nation.[5] The 8 districts include: Creek, Tulsa, Wagoner, Okfuskee, Muskogee, Okmulgee, McIntosh, and Tukvpvtce (Hughes).

Judicial branch

The Nation has two courts: the Muscogee (Creek) Nation District Court and the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has final authority over disputes about the Muscogee Creek Constitution and Laws. The current members of the Supreme Court are as follows:

Chief Justice Kathleen Supernaw

Vice-Chief Justice Montie Deer

Associate Justice Jonodev Chaudhuri

Associate Justice Leah Harjo-Ware

Associate Justice Andrew Adams III

Associate Justice Richard Lerblance[5]

There is a separate Muscogee (Creek) Nation Bar Association (MCNBA).

Enrollment

In 2016, there were 80,591 people enrolled in the Muscogee Creek Nation. Of these, 60,403 lived within the state of Oklahoma.[6] Since 1979, membership to the tribe is based on documented lineal descent from persons listed as Creek 'Indians by Blood' on the Dawes Rolls.[7] The tribe does not have a minimum blood quantum requirement.

Services

Spc. Stacy R. Mull, an enrolled Creek from Okemah, makes frybread at a powwow at Camp Taqaddum, Iraq, 2004.

The Nation operates its own division of housing and issues vehicle license plates.[1] Their Division of Health contracts with Indian Health Services to maintain the Creek Nation Community Hospital and several community clinics, a vocational rehabilitation program, nutrition programs for children and the elderly, and programs dedicated to diabetes, tobacco prevention, and caregivers.[8]

The Muscogee Nation operates the Lighthorse Tribal Police Department, with 43 active employees.[9] The tribe has its own program for enforcing child support payments.

The Mvskoke Food Sovereignty Initiative is sponsored by the nation. It educates and encourages tribal members to grow their own traditional foods for health, environmental sustainability, economic development, and sharing of knowledge and community between generations.[10]

The Muscogee Nation also operates a Communications Department that produces a bi-monthly newspaper, the Muscogee Nation News, and a weekly television show, the Native News Today.

Economic development

The tribe operates a budget in excess of $290 million, has over 4,000 employees, and provides services within their jurisdiction.[11]

The tribe has both gaming (casino related) and non-gaming businesses. Non-gaming business ventures include both Muscogee Nation Business Enterprise[12] (MNBE) and Onefire.[13] MNBE and Onefire oversee economic development as well as investigating, planning, organizing and operating business ventures projects for the tribe related to non-gaming business.[1] Gaming enterprises consist of 9 stand alone casinos; the largest being River Spirit Casino Resort [37] featuring Margaritaville in Tulsa. The revenue from both gaming and non-gaming business are reinvested to develop new businesses, as well as support the welfare of the tribe.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation also operates two Travel Plaza truck stops.

Civic institutions

Tribal college

College of the Muscogee Nation

In 2004, the Muscogee Nation founded a tribal college in Okmulgee, the College of the Muscogee Nation (CMN). CMN is a two-year institution, offering associate degrees in Tribal Services, Police Science, Gaming, and Native American Studies. It offers Mvskoke language classes as well. In 2007, 137 students enrolled, and the college has plans for expansion.[16]

History

The Nation includes the Creek people and descendants of their African-descended slaves[17] who were forced by the US government to relocate from their ancestral homes in the Southeast to Indian Territory in the 1830s, during the Trail of Tears. They signed another treaty with the federal government in 1856.[18]

During the American Civil War, the tribe split into two factions, one allied with the Confederacy and the other, under Opothleyohola, who allied with the Union.[19] There were conflicts between pro-Confederate and pro-Union forces in the Indian Territory during the war. The pro-Confederate forces pursued the loyalists who were leaving to take refuge in Kansas. They fought at the Battle of Round Mountain, Battle of Chusto-Talasah, and Battle of Chustenahlah, resulting in 2,000 deaths among the 9,000 loyalists who were leaving.[20]

After defeating the Confederacy, the Union required new peace treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes. The Treaty of 1866 required the Creek to abolish slavery within their territory and to grant tribal citizenship to the Creek Freedmen who chose to stay in the territory; this citizenship included voting rights and shares of annuities and land allotments.[21] If the Creek Freedmen moved out to United States territory, they would be granted United States citizenship, as were other emancipated slaves.[22]

The Creek established a new government in 1866 and selected a new capital of Okmulgee. In 1867 they ratified a new constitution.[2] They built their capitol in 1867 and enlarged it in 1878. Today the Creek National Capitol is a National Historic Landmark and houses the Creek Council House Museum. The Nation built schools, churches, and public houses during the prosperous final decades of the 19th century, when the tribe had autonomy and minimal interference from the federal government.[2]

At the turn of the century, Congress passed the 1898 Curtis Act, which dismantled tribal governments in another attempt at assimilation; and the Dawes Allotment Act, which broke up tribal landholdings to allot communal land to individual households to encourage adoption of the European-American style of subsistence farming and property ownership. In the hasty process of registration, the Dawes Commission registered tribal members in three categories, distinguishing between "Creek by Blood," "Creek Freedmen," into which category they put anyone with visible African ancestry, regardless of their proportion of Creek ancestry; and "Intermarried Whites." They classified some members of the same families into different groups. The 1906 Five Civilized Tribes Act (April 26, 1906) was passed by the US Congress in anticipation of approving statehood for Oklahoma in 1907. During this time, the Creek had lost more than 2 million acres (8,100 km2) to non-Native settlers and the US government.

Later, when Creek communities organized and set up governments under the 1936 Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act, some former Muscogee tribal towns gained federal recognition.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation did not reorganize and regain federal recognition until 1970. In 1979 the tribe ratified a new constitution that replaced the 1866 constitution.[2] The pivotal 1976 court case Harjo v. Kleppe helped end US federal paternalism. It ushered in an era of growing self-determination. Using the Dawes Rolls as a basis for determining membership of descendants, the Nation enrolled over 58,000 allottees and their descendants.

Creek Freedmen controversy

From 1981-2001, the Creek had membership rules that allowed applicants to use a variety of documentary sources to establish qualifications for membership.

In 1979 the Muscogee Nation Constitutional Convention voted to limit citizenship in the Nation to persons who could prove descent by blood, meaning that members had to be able to document direct descent from an ancestor listed on the Dawes Commission roll in the category of "Creek by Blood". Persons proving they are descended from persons listed as Creek by blood can become citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. The 1893 registry was established to identify citizens of the nation at the time of allotment of communal lands and dissolution of the reservation system and tribal government.[23]

The Freedmen were listed on the Dawes Rolls. Some descendants can prove by documentation in other registers that they had ancestors with Creek blood. The Freedmen had been listed on a separate register, regardless of their proportion of Creek ancestry. This classification did not acknowledge the unions and intermarriage that had taken place for years between the ethnic groups. Prior to the change in code, Creek Freedmen could use existing registers and the preponderance of evidence to establish qualification for citizenship, and were to be aided by the Citizenship Board. The Creek Freedmen have challenged their exclusion from citizenship in legal actions[27][28] which are pending.[29]

Notable Muscogee Nation people

Fred Beaver (1911-1980), artist

R. Perry Beaver (1938-2014), principal chief, football coach

Acee Blue Eagle (1909-1959), actor, artist, author, and educator

Ernest Childers (1918-2005), Lt. Col. in the US Army, first Native American WWII Medal of Honor recipient

Eddie Chuculate (b. 1972), journalist and fiction writer

Helen Chupco (1919-2004), Methodist missionary and tribal councilwoman for 23 years

Fred S. Clinton (1874-1955), surgeon

Sarah Deer (b. 1972), lawyer, professor of law, and MacArthur Fellow

Chitto Harjo (1846-1911), leader of the Crazy Snake Rebellion

Joy Harjo (b. 1959), poet and musician, first Native American United States Poet Laureate

Suzan Shown Harjo, activist, poet, writer, helped gain legislation for religious freedom, repatriation of American Indian remains and artifacts, and authorization for the National Museum of the American Indian

Joan Hill (b. 1930), painter

Isparhecher (1829-1902), political activist, traditionalist leader

Jack Jacobs (1919-1974), football player

William Harjo LoneFight (b. 1966), author, President of Native American Services, languages and cultural activist

Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko 1750-1793), principal chief of the Upper Creek towns

William McIntosh (1775-1825), Creek chief prior to removing to Indian Territory after the Creek War

Opothleyahola (1798 - 1863), Muscogee chief, warrior leader during first two Seminole Wars and the Civil War.

Grant-Lee Phillips (born Bryan G. Phillips), September 1, 1963 is a singer-songwriter.

Pleasant Porter (1840-1907), Principal Chief from 1899-1907

Alexander Posey (1873—1908), poet, humorist, journalist, and politician

Allie Reynolds (1917-1994), Professional baseball player for the Cleveland Indians and New York Yankees

Will Sampson (1933-1987), film actor, noted for his performance in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

Dana Tiger (b. 1961), artist

Johnny Tiger, Jr. (1940–2015), painter and sculptor

France Winddance Twine, sociologist

Micah Ian Wright, writer, videogame designer, graphic novelist, and film director

William Weatherford (1780-1824), Chief Red Eagle, leader of the Red Sticks in Creek Wars

See also

Muscogee (Creek)

Muscogee language

Muscogee mythology

Crazy Snake Rebellion

Green Corn ceremony

Ocmulgee National Monument

Stomp dance