Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

| Author | Giorgio Vasari |

|---|---|

| Original title | |

| Translator | E. L. Seeley |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Subject | Artist biographies |

| Publisher | Torrentino (1550), Giunti (1568) |

Publication date | 1550 (enlarged 1568) |

Published in English | 1908 |

| Pages | 369 (1550), 686 (1568) |

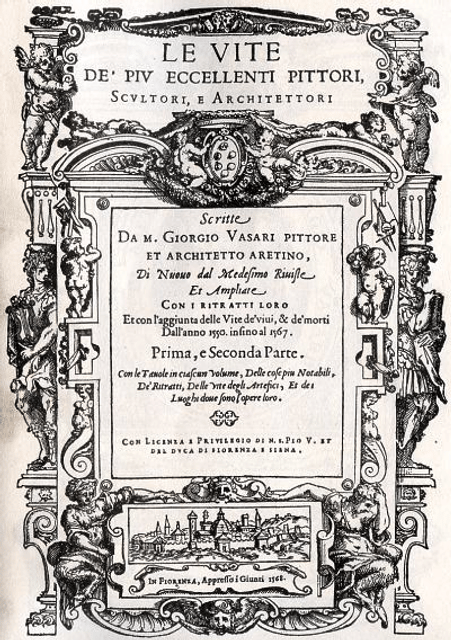

The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (Italian: Le Vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori), also known as The Lives (Italian: Le Vite), is a series of artist biographies written by 16th-century Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, which is considered "perhaps the most famous, and even today the most-read work of the older literature of art",[1] "some of the Italian Renaissance's most influential writing on art",[2] and "the first important book on art history".[3] The title is often abridged to just the Vite or the Lives.

It was first published in two editions with substantial differences between them; the first in 1550 and the second in 1568 (which is the one usually translated and referred to). One important change was the increased attention paid to Venetian art in the second edition, even though Vasari has still been criticised ever since for an excessive emphasis on the art of his native Florence.

| Author | Giorgio Vasari |

|---|---|

| Original title | |

| Translator | E. L. Seeley |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Subject | Artist biographies |

| Publisher | Torrentino (1550), Giunti (1568) |

Publication date | 1550 (enlarged 1568) |

Published in English | 1908 |

| Pages | 369 (1550), 686 (1568) |

Background

As the first Italian art historian, Vasari initiated the genre of an encyclopedia of artistic biographies that continues today. Vasari's work was first published in 1550 by Lorenzo Torrentino in Florence,[4] and dedicated to Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. It included a valuable treatise on the technical methods employed in the arts. It was partly rewritten and enlarged in 1568 and provided with woodcut portraits of artists (some conjectural).

The work has a consistent and notorious favour of Florentines and tends to attribute to them all the new developments in Renaissance art—for example, the invention of engraving. Venetian art in particular, let alone other parts of Europe, is systematically ignored.[5] Between his first and second editions, Vasari visited Venice and the second edition gave more attention to Venetian art (finally including Titian) without achieving a neutral point of view. John Symonds claimed in 1899 that, "It is clear that Vasari often wrote with carelessness, confusing dates and places, and taking no pains to verify the truth of his assertions" (in regards to Vasari's life of Nicola Pisano), while acknowledging that, despite these shortcomings, it is one of the basic sources for information on the Renaissance in Italy.[6]

Vasari's biographies are interspersed with amusing gossip. Many of his anecdotes have the ring of truth, although likely inventions. Others are generic fictions, such as the tale of young Giotto painting a fly on the surface of a painting by Cimabue that the older master repeatedly tried to brush away, a genre tale that echoes anecdotes told of the Greek painter Apelles. He did not research archives for exact dates, as modern art historians do, and naturally his biographies are most dependable for the painters of his own generation and the immediately preceding one. Modern criticism—with all the new materials opened up by research—has corrected many of his traditional dates and attributions. The work is widely considered a classic even today, though it is widely agreed that it must be supplemented by modern scientific research.

Vasari includes a forty-two-page sketch of his own biography at the end of his Vite, and adds further details about himself and his family in his lives of Lazzaro Vasari and Francesco de' Rossi.

Influence

Vasari's Vite has been described as "by far the most influential single text for the history of Renaissance art"[7] and "the most important work of Renaissance biography of artists".[1] Its influence is situated mainly in three domains: as an example for contemporary and later biographers and art historians, as a defining factor in the view on the Renaissance and the role of Florence and Rome in it, and as a major source of information on the lives and works of early Renaissance artists from Italy.

The Vite has been translated wholly or partially into many languages, including English, Dutch, German, Spanish, French and Russian.

Early translations became a model for others

The Vite formed a model for encyclopedias of artist biographies. Different 17th century translators became artist biographers in their own country of origin and were often called the Vasari of their country. Karel Van Mander was probably the first Vasarian author with his Painting book (Het Schilderboeck, 1604), which encompassed not only the first Dutch translation of Vasari, but also the first Dutch translation of Ovid and was accompanied by a list of Italian painters who appeared on the scene after Vasari, and the first comprehensive list of biographies of painters from the Low Countries.[1] Similarly, Joachim von Sandrart, author of Deutsche Akademie (1675), became known as the "German Vasari" and Antonio Palomino, author of An account of the lives and works of the most eminent Spanish painters, sculptors and architects (1724), became the "Spanish Vasari".[8] In England, Aglionby's Painting Illustrated from 1685 was largely based on Vasari as well.[1] In Florence the biographies of artists were revised and implemented in the late 17th century by Filippo Baldinucci.

View of the Renaissance

The Vite is also important as the basis for discussions about the development of style.[9] It influenced the view art historians had of the Early Renaissance for a long time, placing too much emphasis on the achievements of Florentine and Roman artists while ignoring those of the rest of Italy and certainly the artists from the rest of Europe.[10]

Source of information

For centuries, it has been the most important source of information on Early Renaissance Italian (and especially Tuscan) painters and the attribution of their paintings. In 1899, John Addington Symonds used the Vite as one of his basic sources for the description of artists in his seven books on the Renaissance in Italy,[11] and nowadays it is still, despite its obvious biases and shortcomings, the basis for the biographies of many artists like Leonardo da Vinci.[12]

Contents

The Vite contains the biographies of many important Italian artists, and is also adopted as a sort of classical reference guide for their names, which are sometimes used in different ways. The following list respects the order of the book, as divided into its three parts. The book starts with a dedication to Cosimo I de' Medici and a preface, and then starts with technical and background texts about architecture, sculpture, and painting.[13] A second preface follows, introducing the actual "Vite" in parts 2 to 5. What follows is the complete list from the second (1568) edition. In a few cases, different very short biographies were given in one section.

Part 2

Cimabue

Arnolfo di Lapo, with Bonanno

Nicola Pisano

Giovanni Pisano

Andrea Tafi

Gaddo Gaddi

Margaritone

Giotto, with Puccio Capanna

Agostino and Agnolo

Stefano and Ugolino

Pietro Lorenzetti (Pietro Laurati)

Andrea Pisano

Buonamico Buffalmacco

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Ambruogio Laurati)

Pietro Cavallini

Simone Martini with Lippo Memmi

Taddeo Gaddi

Andrea Orcagna (Andrea di Cione)

Tommaso Fiorentino (Giottino)

Giovanni da Ponte

Agnolo Gaddi with Cennino Cennini

Berna Sanese (Barna da Siena)

Duccio

Antonio Viniziano (Antonio Veneziano)

Jacopo di Casentino

Spinello Aretino

Gherardo Starnina

Lippo

Lorenzo Monaco

Taddeo Bartoli

Lorenzo di Bicci with Bicci di Lorenzo and Neri di Bicci

Part 3

Jacopo della Quercia

Niccolo Aretino (Niccolò di Piero Lamberti)

Dello (Dello di Niccolò Delli)

Nanni di Banco

Luca della Robbia with Andrea and Girolamo della Robbia

Paolo Uccello

Lorenzo Ghiberti with Niccolò di Piero Lamberti

Masolino da Panicale

Parri Spinelli

Masaccio

Filippo Brunelleschi

Donatello

Michelozzo Michelozzi with Pagno di Lapo Portigiani

Antonio Filarete and Simone (Simone Ghini)

Giuliano da Maiano

Piero della Francesca

Fra Angelico with Domenico di Michelino and Attavante

Leon Battista Alberti

Lazaro Vasari

Antonello da Messina

Alesso Baldovinetti

Vellano da Padova (Bartolomeo Bellano)

Fra Filippo Lippi with Fra Diamante and Jacopo del Sellaio

Paolo Romano, Mino del Reame, Chimenti Camicia, and Baccio Pontelli

Andrea del Castagno and Domenico Veneziano

Gentile da Fabriano

Vittore Pisanello

Pesello and Francesco Pesellino

Benozzo Gozzoli with Melozzo da Forlì

Francesco di Giorgio and Vecchietta (Lorenzo di Pietro)

Galasso Ferrarese with Cosmè Tura

Antonio and Bernardo Rossellino

Desiderio da Settignano

Mino da Fiesole

Lorenzo Costa with Ludovico Mazzolino

Ercole Ferrarese

Jacopo, Giovanni and Gentile Bellini with Niccolò Rondinelli and Benedetto Coda

Cosimo Rosselli

Il Cecca (Francesco d’Angelo)

Don Bartolomeo Abbate di S. Clemente (Bartolomeo della Gatta) with Matteo Lappoli

Gherardo di Giovanni del Fora

Domenico Ghirlandaio with Benedetto, David Ghirlandaio and Bastiano Mainardi

Antonio Pollaiuolo and Piero Pollaiuolo with Maso Finiguerra

Sandro Botticelli

Benedetto da Maiano

Andrea del Verrocchio with Benedetto and Santi Buglioni

Andrea Mantegna

Filippino Lippi

Bernardino Pinturicchio with Niccolò Alunno and Gerino da Pistoia

Francesco Francia with Caradosso

Pietro Perugino with Rocco Zoppo, Francesco Bacchiacca, Eusebio da San Giorgio and Andrea Aloigi (l'Ingegno)

Vittore Scarpaccia with Stefano da Verona, Jacopo Avanzi, Altichiero, Jacobello del Fiore, Guariento di Arpo, Giusto de' Menabuoi, Vincenzo Foppa, Vincenzo Catena, Cima da Conegliano, Marco Basaiti, Bartolomeo Vivarini, Giovanni di Niccolò Mansueti, Vittore Belliniano, Bartolomeo Montagna, Benedetto Rusconi, Giovanni Buonconsiglio, Simone Bianco, Tullio Lombardo, Vincenzo Civerchio, Girolamo Romani, Alessandro Bonvicino (il Moretto), Francesco Bonsignori, Giovanni Francesco Caroto and Francesco Torbido (il Moro)

Iacopo detto l'Indaco (Jacopo Torni)

Luca Signorelli with Tommaso Bernabei (il Papacello)

Part 4

Giorgione da Castelfranco

Antonio da Correggio

Piero di Cosimo

Donato Bramante (Bramante da Urbino)

Fra Bartolomeo Di San Marco

Mariotto Albertinelli

Raffaellino del Garbo

Pietro Torrigiano (Torrigiano)

Giuliano da Sangallo

Antonio da Sangallo

Raphael

Guillaume de Marcillat

Simone del Pollaiolo (il Cronaca)

Davide Ghirlandaio and Benedetto Ghirlandaio

Domenico Puligo

Andrea da Fiesole

Vincenzo da San Gimignano and Timoteo da Urbino

Andrea Sansovino (Andrea dal Monte Sansovino)

Benedetto da Rovezzano

Baccio da Montelupo and Raffaello da Montelupo (father and son)

Lorenzo di Credi

Boccaccio Boccaccino (Boccaccino Cremonese)

Lorenzetto

Baldassare Peruzzi

Pellegrino da Modena (Pellegrino Aretusi)

Giovan Francesco, also known as il Fattore

Andrea del Sarto

Properzia de’ Rossi, with suor Plautilla Nelli, Lucrezia Quistelli and Sofonisba Anguissola

Alfonso Lombardi

Michele Agnolo (Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli)

Girolamo Santacroce

Dosso Dossi and Battista Dossi (Dossi brothers)

Giovanni Antonio Licino

Rosso Fiorentino

Giovanni Antonio Sogliani

Girolamo da Treviso (Girolamo Da Trevigi)

Polidoro da Caravaggio and Maturino da Firenze (Maturino Fiorentino)

Bartolommeo Ramenghi (Bartolomeo Da Bagnacavallo)

Marco Calabrese

Morto Da Feltro

Franciabigio

Francesco Mazzola (Il Parmigianino)

Jacopo Palma (Il Palma)

Lorenzo Lotto

Fra Giocondo

Francesco Granacci

Baccio d'Agnolo

Valerio Vicentino (Valerio Belli), Giovanni da Castel Bolognese (Giovanni Bernardi) and Matteo dal Nasaro Veronese

Part 5

Marcantonio Bolognese

Antonio da Sangallo

Giulio Romano

Sebastiano del Piombo (Sebastiano Viniziano)

Perino Del Vaga

Domenico Beccafumi

Giovann'Antonio Lappoli

Niccolò Soggi

Niccolò detto il Tribolo

Pierino da Vinci

Baccio Bandinelli

Giuliano Bugiardini

Cristofano Gherardi

Jacopo da Pontormo

Simone Mosca

Girolamo Genga, Bartolommeo Genga and Giovanbatista San Marino (Giovanni Battista Belluzzi)

Michele Sanmicheli with Paolo Veronese (Paulino) and Paolo Farinati

Giovannantonio detto il Soddoma da Verzelli

Bastiano detto Aristotile da San Gallo

Benedetto Garofalo and Girolamo da Carpi with Bramantino and Bernardino Gatti (il Soiaro)

Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, Davide Ghirlandaio and Benedetto Ghirlandaio

Giovanni da Udine

Battista Franco with Jacopo Tintoretto and Andrea Schiavone

Francesco Rustichi

Fra' Giovann'Agnolo Montorsoli

Francesco detto de' Salviati with Giuseppe Porta

Daniello Ricciarelli da Volterra

Taddeo Zucchero with Federico Zuccari

Part 6

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Michelangelo) with Tiberio Calcagni and Marcello Venusti

Francesco Primaticcio with Giovanni Battista Ramenghi (il Bagnacavallo Jr.), Prospero Fontana, Niccolò dell'Abbate, Domenico del Barbieri, Lorenzo Sabatini, Pellegrino Tibaldi, Luca Longhi, Livio Agresti, Marco Marchetti, Giovanni Boscoli and Bartolomeo Passarotti

Tiziano da Cadore (Titian) with Jacopo Bassano, Giovanni Maria Verdizotti, Jan van Calcar (Giovanni fiammingo) and Paris Bordon

Jacopo Sansovino with Andrea Palladio, Alessandro Vittoria, Bartolomeo Ammannati and Danese Cattaneo

Lione Aretino (Leone Leoni) with Guglielmo Della Porta and Galeazzo Alessi

Giulio Clovio, manuscript illuminator

Various Italian artists: Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta, Marcello Venusti, Iacopino del Conte, Dono Doni, Cesare Nebbia and Niccolò Circignani detto il Pomarancio

Bronzino

Giorgio Vasari

Editions

There have been numerous editions and translations of the Lives over the years. Many have been abridgements due to the great length of the original. The most recent new English translation is by Peter and Julia Conaway Bondanella, published in the Oxford World's Classics series in 1991.[14]

Versions online

“Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists.” [27] Website created by Adrienne DeAngelis. Currently incomplete, intended to be unabridged, in English.

Le Vite. [28] Selections of the 1550 edition (drawn from a 1768 reprint), in Italian.

1568 edition [29] on Google Books Part III, v. 1 (from Leonardo to Perino del Vaga), in Italian

Le Vite. [30] 1568 edition, Part III, v. 2 (from Beccafumi to Vasari), in Italian

Stories Of The Italian Artists From Vasari. [31] Translated by E. L. Seeley, 1908. Abridged, in English.

Le vite Progetto Manuzio [32] , 1550 edition in Italian

See also

Egg of Columbus (Lives contains a similar story to the Columbus' egg story)