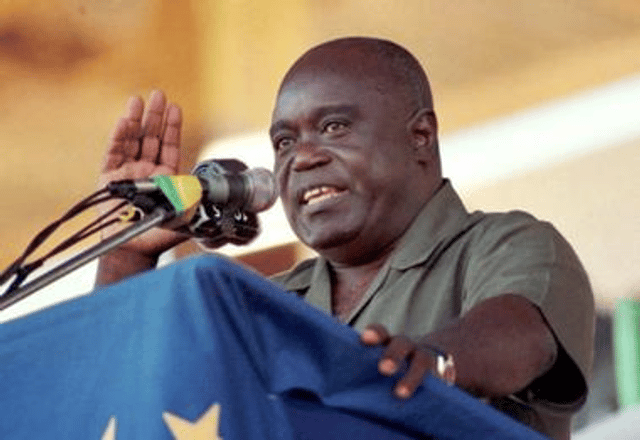

Laurent-Désiré Kabila

Laurent-Désiré Kabila

Laurent-Désiré Kabila | |

|---|---|

| 3rd President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| In office May 17, 1997 – January 16, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Mobutu Sese Seko (as President of Zaire) |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Kabila |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1939-11-27)November 27, 1939 Baudouinville, Belgian Congo |

| Died | January 16, 2001(2001-01-16)(aged 61) Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Congolese |

| Political party | People's Revolution Party (1967–1996) Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (1996–1997) Independent (1997–2001) |

| Spouse(s) | Sifa Mahanya |

| Children | Aimée Kabila Mulengela (1976–2008) Jaynet Kabila Joseph Kabila Zoé Kabila |

| Alma mater | University of Dar es Salaam |

| Profession | Rebel leader, President |

Laurent-Désiré Kabila (French pronunciation: lo.ʁɑ̃ de.zi.ʁe ka.bi.la) (November 27, 1939 – January 16, 2001), or simply Laurent Kabila (US: pronunciation ), was a Congolese revolutionary and politician who served as the third President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from May 17, 1997, when he overthrew Mobutu Sese Seko, until his assassination by one of his bodyguards on January 16, 2001.[1] He was succeeded eight days later by his 29-year-old son Joseph.

Laurent-Désiré Kabila | |

|---|---|

| 3rd President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| In office May 17, 1997 – January 16, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Mobutu Sese Seko (as President of Zaire) |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Kabila |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1939-11-27)November 27, 1939 Baudouinville, Belgian Congo |

| Died | January 16, 2001(2001-01-16)(aged 61) Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Congolese |

| Political party | People's Revolution Party (1967–1996) Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (1996–1997) Independent (1997–2001) |

| Spouse(s) | Sifa Mahanya |

| Children | Aimée Kabila Mulengela (1976–2008) Jaynet Kabila Joseph Kabila Zoé Kabila |

| Alma mater | University of Dar es Salaam |

| Profession | Rebel leader, President |

Early life

Kabila was born to a member of the Luba people in Baudoinville, Katanga Province, (now Moba, Tanganyika Province) in the Belgian Congo. His father was a Luba and his mother was a Lunda. It is claimed that he studied abroad (political philosophy in Paris, got a PhD in Tashkent, in Belgrade and at last in Dar es Salaam) but no proof has been found or provided.[2]

Political activities

Congo crisis

Shortly after the Congo achieved independence in 1960, Katanga seceded under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe. Kabila organised the Baluba in an anti-secessionist rebellion in Manono. In September 1962 a new province, North Katanga, was established, and he became a member of the provincial assembly[3] and served as chief of cabinet for Minister of Information Ferdinand Tumba.[4] In September 1963 he and other young members of the assembly were forced to resign, facing allegations of communist sympathies.[3]

Kabila established himself as a supporter of hard-line Lumumbist Prosper Mwamba Ilunga. When the Lumumbists formed the Conseil National de Libération, he was sent to eastern Congo to help organize a revolution, in particular in the Kivu and North Katanga provinces. In 1965, Kabila set up a cross-border rebel operation from Kigoma, Tanzania, across Lake Tanganyika.[4]

Che Guevara

Che Guevara assisted Kabila for a short time in 1965. Guevara had appeared in the Congo with approximately 100 men who planned to bring about a Cuban-style revolution. Guevara judged Kabila (then 26) as "not the man of the hour" he had alluded to, being too distracted. This, in Guevara's opinion, accounted for Kabila showing up days late at times to provide supplies, aid, or backup to Guevara's men. The lack of cooperation between Kabila and Guevara contributed to the suppression of the revolt that same year.[5]

In Guevara's view, of all of the people he met during his campaign in Congo, only Kabila had "genuine qualities of a mass leader"; but Guevara castigated Kabila for a lack of "revolutionary seriousness". After the failure of the rebellion, Kabila turned to smuggling gold and timber on Lake Tanganyika. He also ran a bar and brothel in Tanzania.[6]

Marxist mini-state (1967–1988)

In 1967, Kabila and his remnant of supporters moved their operation into the mountainous Fizi – Baraka area of South Kivu in the Congo, and founded the People's Revolutionary Party (PRP). With the support of the People's Republic of China, the PRP created a secessionist Marxist state in South Kivu province, west of Lake Tanganyika.

The PRP state came to an end in 1988 and Kabila disappeared and was widely believed to be dead. While in Kampala, Kabila reportedly met Yoweri Museveni, the future president of Uganda. Museveni and former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere later introduced Kabila to Paul Kagame, who would become president of Rwanda. These personal contacts became vital in mid-1990s, when Uganda and Rwanda sought a Congolese face for their intervention in Zaire.[7][8]

First Congo War

Kabila returned in October 1996, leading ethnic Tutsis from South Kivu against Hutu forces, marking the beginning of the First Congo War. With support from Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi, Kabila pushed his forces into a full-scale rebellion against Mobutu as the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (ADFL).

By mid-1997, the ADFL had almost completely overrun the country and the remains of Mobutu's army. Only the country's decrepit infrastructure slowed Kabila's forces down; in many areas, the only means of transit were irregularly used dirt paths.[9] Following failed peace talks held on board of the South African ship SAS Outeniqua, Mobutu fled into exile on 16 May.

The next day, from his base in Lubumbashi, Kabila proclaimed himself president. Kabila suspended the Constitution, and changed the name of the country from Zaire to the Democratic Republic of the Congo—the country's official name from 1964 to 1971. He made his grand entrance into Kinshasa on 20 May and was sworn in on 31 May, officially commencing his term as president.

Presidency (1997–2001)

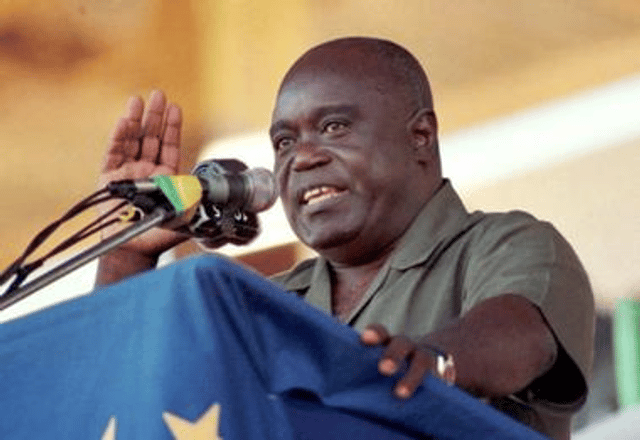

The Flag of the Democratic Republic of the Congo used by Kabila.

Kabila had been a committed Marxist, but his policies at this point were a mix of capitalism and socialism. He declared that elections would not be held for two years, since it would take him at least that long to restore order. While some in the West hailed Kabila as representing a "new breed" of African leadership, critics charged that Kabila's policies differed little from his predecessor's, being characterised by authoritarianism, corruption, and human rights abuses. As early as late 1997, Kabila was being denounced as "another Mobutu".[10]

By 1998, Kabila's former allies in Uganda and Rwanda had turned against him and backed a new rebellion of the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), the Second Congo War. Kabila found new allies in Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, and managed to hold on in the south and west of the country and by July 1999, peace talks led to the withdrawal of most foreign forces.

Assassination

Laurent-Désiré Kabila's son and successor, Joseph Kabila

Kabila was shot and killed in his office on 16 January 2001.[11]

The DRC's authorities managed to keep power, despite Kabila's assassination. The exact circumstances are still disputed. Kabila reportedly died on the spot, according to DRC's then health minister Leonard Mashako Mamba, who was in the next door office when Kabila was shot and arrived immediately after the assassination. The government claimed that Kabila was still alive, however, when he was flown to a hospital in Zimbabwe after he was shot so that DRC authorities could organize the tense succession.

The Congolese government announced that he had died of his wounds on 18 January. One week later, his body was returned to Congo for a state funeral and his son, Joseph Kabila, became president ten days later.[12] By doing so, DRC officials were accomplishing the "verbal testimony" of the deceased President. Then Justice Minister Mwenze Kongolo and Kabila's aide-de-camp Eddy Kapend have reported that Kabila had told them that his son Joseph, then number two of the army, should take over, if he were to die in office.

The investigation into Kabila's assassination led to 135 people – including four children – being tried before a special military tribunal. The alleged ringleader, Colonel Eddy Kapend (one of Kabila's cousins), and 25 others were sentenced to death in January 2003, but not executed. Of the other defendants 64 were jailed, with sentences from six months to life, and 45 were exonerated. Some individuals were also accused of being involved in a plot to overthrow his son. Among them was Kabila's special advisor Emmanuel Dungia, former ambassador to South Africa. Many people believe the trial was flawed and the convicted defendants innocent.[13][14]