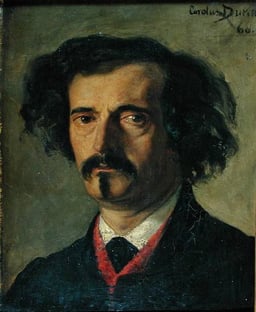

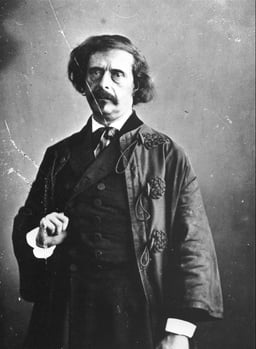

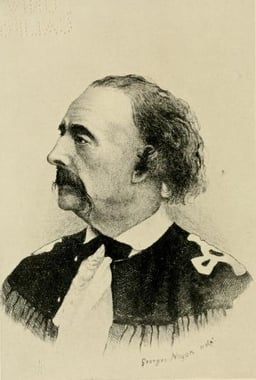

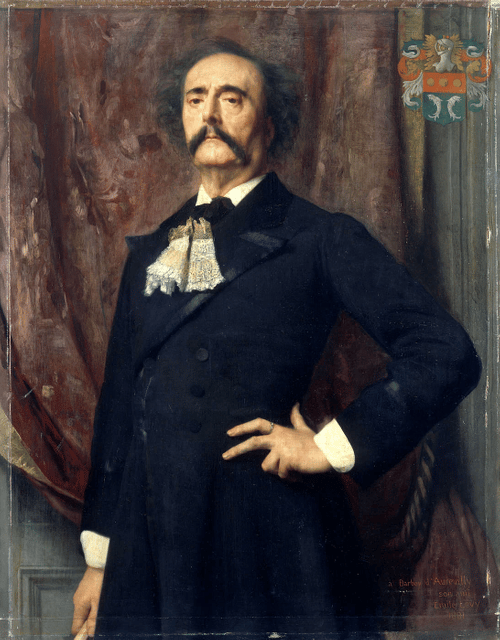

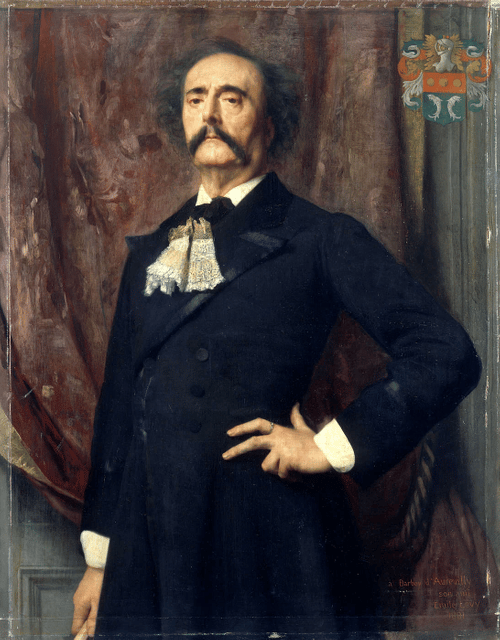

Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly

Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly

Jules-Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly (2 November 1808 – 23 April 1889) was a French novelist and short story writer. He specialised in mystery tales that explored hidden motivation and hinted at evil without being explicitly concerned with anything supernatural. He had a decisive influence on writers such as Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, Henry James, Leon Bloy, and Marcel Proust.

Biography

Jules-Amédée Barbey — the d'Aurevilly was a later inheritance from a childless uncle — was born at Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, Manche in Lower Normandy. In 1827 he went to the Collège Stanislas de Paris. After getting his baccalauréat in 1829, he went to Caen University to study law, taking his degree three years later. As a young man, he was a liberal and an atheist,[2] and his early writings present religion as something that meddles in human affairs only to complicate and pervert matters.[3][4] In the early 1840s, however, he began to frequent the Catholic and legitimist salon of Baroness Amaury de Maistre, niece of Joseph de Maistre. In 1846 he converted to Roman Catholicism.

His greatest successes as a literary writer date from 1852 onwards, when he became an influential literary critic at the Bonapartist paper Le Pays, helping to rehabilitate Balzac and effectually promoting Stendhal, Flaubert, and Baudelaire. Paul Bourget describes Barbey as an idealist, who sought and found in his work a refuge from the uncongenial ordinary world. Jules Lemaître, a less sympathetic critic, thought the extraordinary crimes of his heroes and heroines, his reactionary opinions, his dandyism and snobbery were a caricature of Byronism.

Beloved of fin-de-siècle decadents, Barbey d'Aurevilly remains an example of the extremes of late romanticism. Barbey d'Aurevilly held strong Catholic opinions,[5][6] yet wrote about risqué subjects, a contradiction apparently more disturbing to the English than to the French themselves. Barbey d'Aurevilly was also known for having constructed his own persona as a dandy, adopting an aristocratic style and hinting at a mysterious past, though his parentage was provincial bourgeois nobility, and his youth comparatively uneventful.

Inspired by the character and ambience of Valognes, he set his works in the society of Normand aristocracy. Although he himself did not use the Norman patois, his example encouraged the revival of vernacular literature in his home region.

Jules-Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly died in Paris and was buried in the cimetière de Montparnasse. During 1926 his remains were transferred to the churchyard in Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte.

Works

Fiction

Le Cachet d’Onyx (1831).

Léa (1832).

L'Amour Impossible (1841).

La Bague d’Annibal (1842).

Une vieille maîtresse (A Former Mistress, 1851)[1]

L'Ensorcelée (The Bewitched, 1852; an episode of the royalist rising among the Norman peasants against the first republic).

Le Chevalier Des Touches (1863)

Un Prêtre Marié (1864)

Les Diaboliques (The She-Devils, 1874; a collection of short stories, each of which relates a tale of a woman who commits an act of violence or revenge, or other crime).

Une Histoire sans Nom (The Story Without a Name, 1882).

Ce qui ne Meurt Pas (What Never Dies, 1884).

Essays and criticism

Du Dandysme et de Georges Brummel (The Anatomy of Dandyism, 1845).

Les Prophètes du Passé (1851).

Les Oeuvres et les Hommes (1860–1909).

Les Quarante Médaillons de l'Académie (1864).

Les Ridicules du Temps (1883).

Pensées Détachées (1889).

Fragments sur les Femmes (1889).

Polémiques d'hier (1889).

Dernières Polémiques (1891).

Goethe et Diderot (1913).

L'Europe des Écrivains (2000).

Le Traité de la Princesse ou la Princesse Maltraitée (2012).

Poetry

Ode aux Héros des Thermopyles (1825).

Poussières (1854).

Amaïdée (1889).

Rythmes Oubliés (1897).

Translated into English

The Story without a Name. New York: Belford and Co. (1891, translated by Edgar Saltus). The Story without a Name. New York: Brentano's (1919).

Of Dandyism and of George Brummell. London: J.M. Dent (1897, translated by Douglas Ainslie). Dandyism. New York: PAJ Publications (1988).

Weird Women: Being a Literal Translation of "Les Diaboliques". London and Paris: Lutetian Bibliophiles' Society (2 vols., 1900). The Diaboliques. New York: A.A. Knopf (1925, translated by Ernest Boyd). "Happiness in Crime." In: Shocking Tales. New York: A.A. Wyn Publisher (1946). The She-devils. London: Oxford University Press (1964, translated by Jean Kimber).

What Never Dies: A Romance. New York: A.R. Keller (1902).[7] What Never Dies: A Romance. London: The Fortune Press (1933).

Bewitched. New York and London: Harper & brothers (1928, translated by Louise Collier Willcox).

His complete works are published in two volumes of the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

Quotations

"Next to the wound, what women make best is the bandage."[8]

"The mortal envelope of the Middle Age has disappeared, but the essential remains. Because the temporal disguise has fallen, the dupes of history and of its dates say that the Middle Age is dead. Does one die for changing his shirt?"[9]

"In France everybody is an aristocrat, for everybody aims to be distinguished from everybody. The red cap of the Jacobins is the red heel of the aristocrats at the other extremity, but it is the same distinctive sign. Only, as they hated each other, Jacobinism placed on its head what aristocracy placed under its foot."[10]

"In the matter of literary form it is the thing poured in the vase which makes the beauty of the vase, otherwise there is nothing more than a vessel."[11]

"Books must be set against books, as poisons against poisons."[12]

"When superior men are mistaken they are superior in that as in all else. They see more falsely than small or mediocre minds."[13]

"The Orient and Greece recall to my mind the saying, so colored and melancholic, of Richter: 'Blue is the color of mourning in the Orient. That is why the sky of Greece is so beautiful'."[14]

"Men give their measure by their admiration, and it is by their judgments that one may judge them."[15]

"The most beautiful destiny: to have genius and be obscure."[16]