Itō Hirobumi

Itō Hirobumi

Prince Itō Hirobumi | |

|---|---|

伊藤博文 | |

| President of the Privy Council of Japan | |

| In office 14 June 1909 – 26 October 1909 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| Succeeded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| In office 13 July 1903 – 21 December 1905 | |

| Preceded by | Saionji Kinmochi |

| Succeeded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| In office 1 June 1891 – 8 August 1892 | |

| Preceded by | Oki Takato |

| Succeeded by | Oki Takato |

| In office 30 April 1888 – 30 October 1889 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Oki Takato |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 19 October 1900 – 10 May 1901 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| Succeeded by | Saionji Kinmochi(Acting) |

| In office 12 January 1898 – 30 June 1898 | |

| Preceded by | Matsukata Masayoshi |

| Succeeded by | Ōkuma Shigenobu |

| In office 8 August 1892 – 31 August 1896 | |

| Preceded by | Matsukata Masayoshi |

| Succeeded by | Kuroda Kiyotaka(Acting) |

| In office 22 December 1885 – 30 April 1888 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Kuroda Kiyotaka |

Additional positions | |

| President of the House of Peers | |

| In office 24 October 1890 – 20 July 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Hachisuka Mochiaki |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan | |

| In office September 1887 – February 1888 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Inoue Kaoru |

| Succeeded by | Ōkuma Shigenobu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hayashi Risuke (1841-10-16)16 October 1841 Tsukari, Yamaguchi, Japan |

| Died | 26 October 1909(1909-10-26)(aged 68) Harbin, Jilin, China |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Hirobumi Ito Cemetery, Tokyo, Japan |

| Political party | Independent(Before 1900) Constitutional Association of Political Friendship(1900–1909) |

| Spouse(s) | Itō Umeko (1848–1924) |

| Children | 3 sons, 2 daughters |

| Father | Itō Jūzō |

| Alma mater | Shoka Sonjuku University College London |

| Signature |  |

Prince Itō Hirobumi (伊藤 博文, 16 October 1841 – 26 October 1909, born Hayashi Risuke and also known as Hirofumi, Hakubun and briefly during his youth Itō Shunsuke) was a Japanese statesman and genrō. A London-educated samurai of the Chōshū Domain and an influential figure in the early Meiji Restoration government, he chaired the bureau which drafted the Meiji Constitution in the 1880s. Looking to the West for legal inspiration, Itō rejected the United States Constitution as too liberal and the Spanish Restoration as too despotic before ultimately drawing on the British and German models, especially the Prussian Constitution of 1850. Dissatisfied with the prominent role of Christianity in European legal traditions, he substituted references to the more traditionally Japanese concept of kokutai or "national polity", which became the constitutional justification for imperial authority.

In 1885, he became Japan's first Prime Minister, an office his constitutional bureau had introduced. He went on to hold the position four times, becoming one of the longest serving PMs in Japanese history, and wielded considerable power even out of office as the occasional head of Emperor Meiji's Privy Council. A monarchist, Itō favoured a large, bureaucratic government and opposed the formation of political parties. His third term in government was ended by the consolidation of the opposition into the Kenseitō party in 1898, prompting him to found the Rikken Seiyūkai party in response. He resigned his fourth and final ministry in 1901 after growing weary of party politics, but served as head of the Privy Council twice more before his death. Itō's foreign policy was ambitious. He strengthened diplomatic ties with Western powers including Germany, the United States and especially the United Kingdom. In Asia he oversaw the First Sino-Japanese War and negotiated Chinese surrender on terms aggressively favourable to Japan, including the annexation of Taiwan and the release of Korea from the Chinese Imperial tribute system. Itō sought to avoid a Russo-Japanese War through the policy of Man-Kan kōkan – surrendering Manchuria to the Russian sphere of influence in exchange for the acceptance of Japanese hegemony in Korea. A diplomatic tour of the United States and Europe brought him to Saint Petersburg in November 1901, where he was unable to find compromise on this matter with Russian authorities. Soon the government of Katsura Tarō elected to abandon the pursuit of Man-Kan kōkan, and tensions with Russia continued to escalate towards war.

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 made Itō the first Japanese Resident-General of Korea. He initially supported the sovereignty of the indigenous Joseon monarchy as a protectorate under Japan, but he eventually accepted and agreed with the increasingly powerful Imperial Japanese Army, which favoured the total annexation of Korea, resigning his position as Resident-General and taking a new position as the President of the Privy Council of Japan in 1909. Four months later, Itō was assassinated by Korean-independence activist and nationalist An Jung-geun in Manchuria.[1][2] The annexation process was formalised by another treaty the following year after Ito's death. Through his daughter Ikuko, Itō was the father-in-law of politician, intellectual and author Suematsu Kenchō.

Prince Itō Hirobumi | |

|---|---|

伊藤博文 | |

| President of the Privy Council of Japan | |

| In office 14 June 1909 – 26 October 1909 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| Succeeded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| In office 13 July 1903 – 21 December 1905 | |

| Preceded by | Saionji Kinmochi |

| Succeeded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| In office 1 June 1891 – 8 August 1892 | |

| Preceded by | Oki Takato |

| Succeeded by | Oki Takato |

| In office 30 April 1888 – 30 October 1889 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Oki Takato |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 19 October 1900 – 10 May 1901 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Yamagata Aritomo |

| Succeeded by | Saionji Kinmochi(Acting) |

| In office 12 January 1898 – 30 June 1898 | |

| Preceded by | Matsukata Masayoshi |

| Succeeded by | Ōkuma Shigenobu |

| In office 8 August 1892 – 31 August 1896 | |

| Preceded by | Matsukata Masayoshi |

| Succeeded by | Kuroda Kiyotaka(Acting) |

| In office 22 December 1885 – 30 April 1888 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Kuroda Kiyotaka |

Additional positions | |

| President of the House of Peers | |

| In office 24 October 1890 – 20 July 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Hachisuka Mochiaki |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan | |

| In office September 1887 – February 1888 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Inoue Kaoru |

| Succeeded by | Ōkuma Shigenobu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hayashi Risuke (1841-10-16)16 October 1841 Tsukari, Yamaguchi, Japan |

| Died | 26 October 1909(1909-10-26)(aged 68) Harbin, Jilin, China |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Hirobumi Ito Cemetery, Tokyo, Japan |

| Political party | Independent(Before 1900) Constitutional Association of Political Friendship(1900–1909) |

| Spouse(s) | Itō Umeko (1848–1924) |

| Children | 3 sons, 2 daughters |

| Father | Itō Jūzō |

| Alma mater | Shoka Sonjuku University College London |

| Signature |  |

Life

Early years

Letter of Itō Hirobumi

Itō's birth name was Hayashi Risuke (林利助). His father Hayashi Jūzō was the adopted son of Mizui Buhei who was an adopted son of Itō Yaemon's family, a lower-ranked samurai from Hagi in Chōshū Domain (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture). Mizui Buhei was renamed Itō Naoemon. Mizui Jūzō took the name Itō Jūzō, and Hayashi Risuke was renamed to Itō Shunsuke at first, then Itō Hirobumi. He was a student of Yoshida Shōin at the Shōka Sonjuku and later joined the Sonnō jōi movement ("to revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians"), together with Katsura Kogorō. Itō was chosen as one of the Chōshū Five who studied at University College London in 1863, and the experience in Great Britain convinced him Japan needed to adopt Western ways.

In 1864, Itō returned to Japan with fellow student Inoue Kaoru to attempt to warn Chōshū Domain against going to war with the foreign powers (the Bombardment of Shimonoseki) over the right of passage through the Straits of Shimonoseki. At that time, he met Ernest Satow for the first time, later a lifelong friend.

Political career

Photo of the leading members of the Iwakura mission

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Itō was appointed governor of Hyōgo Prefecture, junior councilor for Foreign Affairs, and sent to the United States in 1870 to study Western currency systems. Returning to Japan in 1871, he established Japan's taxation system. With the advice of Edmund Morel, a chief engineer of the railway department, Ito endeavored to found the Public Works together with Yamao Yozo. Later that year, he was sent on the Iwakura Mission around the world as vice-envoy extraordinary, during which he won the confidence of Ōkubo Toshimichi, one of the leaders of the Meiji government.

In 1873, Itō was made a full councilor, Minister of Public Works, and in 1875 chairman of the first Assembly of Prefectural Governors. He participated in the Osaka Conference of 1875. After Ōkubo's assassination, he took over the post of Home Minister and secured a central position in the Meiji government. In 1881 he urged Ōkuma Shigenobu to resign, leaving himself in unchallenged control.

Itō went to Europe in 1882 to study the constitutions of those countries, spending nearly 18 months away from Japan. While working on a constitution for Japan, he also wrote the first Imperial Household Law and established the Japanese peerage system (kazoku) in 1884.

In 1885, he negotiated the Convention of Tientsin with Li Hongzhang, normalizing Japan's diplomatic relations with Qing-dynasty China.

As Prime Minister

Portrait of Ito Hirobumi, c. 1895

Picture of Hirobumi Itō

Portrait of Hirobumi Itō in an American book

In 1885, based on European ideas, Itō established a cabinet system of government, replacing the Daijō-kan as the decision-making state organization, and on December 22, 1885, he became the first prime minister of Japan.

On April 30, 1888, Itō resigned as prime minister, but headed the new Privy Council to maintain power behind-the-scenes. In 1889, he also became the first genrō. The Meiji Constitution was promulgated in February 1889. He had added to it the references to the kokutai or "national polity" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign.[3] This stemmed from his rejection of some European notions as unfit for Japan, as they stemmed from European constitutional practice and Christianity.[3]

He remained a powerful force while Kuroda Kiyotaka and Yamagata Aritomo, his political nemeses, were prime ministers.

During Itō's second term as prime minister (August 8, 1892 – August 31, 1896), he supported the First Sino-Japanese War and negotiated the Treaty of Shimonoseki in March 1895 with his ailing foreign minister Mutsu Munemitsu. In the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1894, he succeeded in removing some of the onerous unequal treaty clauses that had plagued Japanese foreign relations since the start of the Meiji period.

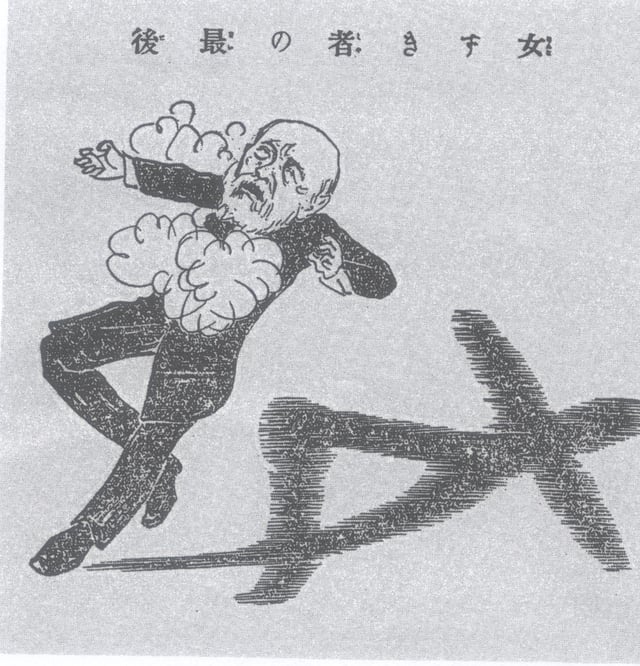

During Itō's third term as prime minister (January 12 – June 30, 1898), he encountered problems with party politics. Both the Jiyūtō and the Shimpotō opposed his proposed new land taxes, and in retaliation, Itō dissolved the Diet and called for new elections. As a result, both parties merged into the Kenseitō, won a majority of the seats, and forced Itō to resign. This lesson taught Itō the need for a pro-government political party, so he organized the Rikken Seiyūkai (Constitutional Association of Political Friendship) in 1900. Itō's womanizing was a popular theme in editorial cartoons and in parodies by contemporary comedians, and was used by his political enemies in their campaign against him.

Itō returned to office as prime minister for a fourth term from October 19, 1900, to May 10, 1901, this time facing political opposition from the House of Peers. Weary of political back-stabbing, he resigned in 1901, but remained as head of the Privy Council as the premiership alternated between Saionji Kinmochi and Katsura Tarō.

Toward the end of August 1901, Itō announced his intention of visiting the United States to recuperate. This turned into a long journey in the course of which he visited the major cities of the United States and Europe, setting off from Yokohama on September 18, traveling through the U.S. to New York City (Itō received an honorary doctorate LL.D. from Yale University in late October[4]), from which he sailed to Boulogne, reaching Paris on November 4. On November 25, he reached Saint Petersburg, having been asked by the new prime minister, Katsura Tarō, to sound out the Russians, entirely unofficially, on their intentions in the Far East. Japan hoped to achieve what it called Man-Kan kōkan, the exchange of a free hand for Russia in Manchuria for a free hand for Japan in Korea, but Russia, feeling greatly superior to Japan and unwilling to give up its ability to use Korean ports for its navy, was in no mood to compromise; its foreign minister, Vladimir Lamsdorf, "thought that time was on the side of his country because of the (Trans-Siberian) railway and there was no need to make concessions to the Japanese."[5] Itō left empty-handed for Berlin (where he received honors from Kaiser Wilhelm), Brussels, and London. Meanwhile, Katsura had decided that Man-Kan kōkan was no longer desirable for Japan, which should not renounce activity in Manchuria. When Itō reached London, he had talks with Lord Lansdowne which helped lay the groundwork for the Anglo-Japanese Alliance announced early the following year. The failure of his mission to Russia was "one of the most important events in the run-up to the Russo-Japanese War".[6]

It was during his terms as Prime Minister that he invited Professor George Trumbull Ladd of Yale University to serve as a diplomatic adviser to promote mutual understanding between Japan and the United States. It was because of his series of lectures he delivered in Japan revolutionizing its educational methods, that he was the first foreigner to receive the Second Class honor (conferred by the Meiji Emperor in 1907) and the Third Class honor (conferred by The Meiji Emperor in 1899), Orders of the Rising Sun. He later wrote a book on his personal experiences in Korea and with Resident-General Itō.[7][8][9] When he died, half his ashes were buried in a Buddhist temple in Tokyo and a monument was erected to him.[8][10]

As Resident-General of Korea

Prince Itō and the Crown Prince of Korea Yi Un

In November 1905, following the Russo-Japanese War, the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 was made between the Empire of Japan and the Empire of Korea,[11][12] making Korea a Japanese protectorate. After the treaty had been signed, Itō became the first Resident-General of Korea on December 21, 1905. In 1907, he urged Emperor Gojong to abdicate in favor of his son Sunjong and secured the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907, giving Japan its authority to control Korea's internal affairs. Itō's position, however, was nuanced. He was firmly against Korea falling into China or Russia's sphere of influence, which would cause a grave threat to Japan's national security. He was initially against radical annexation, advocating instead that Korea should remain as a protectorate. When the cabinet eventually voted for annexing Korea, he insisted and proposed a delay, hoping that the annexation decision could be reversed in the future.[13] His political nemesis came when the politically influential Imperial Japanese Army, led by Yamagata Aritomo, whose main faction was advocating annexation forced Itō to resign on June 14, 1909. However, prior to the cabinet's annexation decision and his resignation on June 14, 1909, Itō had already changed his mind on his original stance of keeping Korea as a "protectorate", approving the annexation of Korea after Katsura Tarō and Komura Jutarō presented Japan's future annexation plans to him on April 10, 1909 (his securing of the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907 laid the groundwork for a full annexation of Korea, discrediting the claim that Itō was purely in favor of a "protectorate" Korea).[14] His assassination is believed to have accelerated the path to the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty.[15]

Assassination

Ito (second on the left) before being gunned down by An Jung-geun

A Japanese Cartoon describing the scene when Ito was shot to death. His shadow forms the kanji character for "woman", referencing his alleged penchant for carnal pleasures.

Itō arrived at the Harbin railway station on October 26, 1909 for a meeting with Vladimir Kokovtsov, a Russian representative in Manchuria. There An Jung-geun, a Korean nationalist[15] and independence activist,[16][17] fired six shots, three of which hit Itō in the chest. He died shortly thereafter. His body was returned to Japan on the Imperial Japanese Navy cruiser Akitsushima, and he was accorded a state funeral.[18] An Jung-geun later listed "15 reasons why Itō should be killed" at his trial.[19][20]

Legacy

In Japan

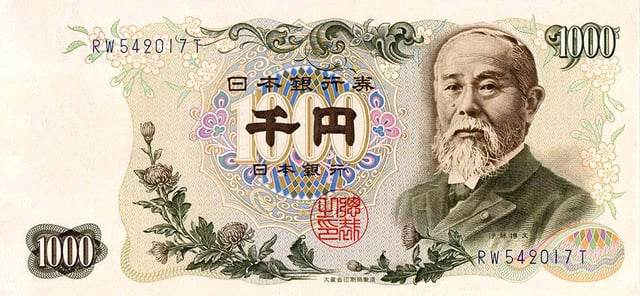

A Series C 1,000 yen note of Japan, with a portrait of Itō Hirobumi.

A portrait of Itō Hirobumi was on the obverse of the Series C 1,000 yen note from 1963 until a new series was issued in 1984. Itō's former house in Shinagawa, Tokyo has been transported to the site of his childhood home in Yamaguchi prefecture. It is now preserved as a museum near the Shōin Jinja in Hagi. The publishing company Hakubunkan takes its name from Hakubun, an alternate pronunciation of Itō's given name.

In Korea

The Annals of Sunjong record that Gojong held a positive view of Itō's governorship. In an entry for October 28, 1909, almost three years after being forced to abdicate his throne, the former emperor praised Itō, who died two days earlier, for his efforts to develop civilization in Korea. However, the integrity of Joseon silloks dated after the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 is dubious due to the influence exerted over record-keeping by the Japanese. Among all the dynasty's annals, only those of the two post-treaty monarchs, Gojong and Sunjong, are singled out as unreliable by the National Institute of Korean History. These are furthermore the only silloks not regarded as national treasures by South Korea or Memories of the World by UNESCO.[21]

Itō has been portrayed several times in Korean cinema. His assassination was the subject of North Korea's An Jung-gun Shoots Ito Hirobumi in 1979 and South Korea's Thomas Ahn Joong Keun in 2004; both films made his assassin An Jung-geun the protagonist. The 1973 South Korean film Femme Fatale: Bae Jeong-ja is a biopic of Itō's adopted Korean daughter Bae Jeong-ja (1870–1950).

Itō argued that if East Asians did not cooperate closely with each other, Japan, Korea and China would all fall victim to Western imperialism. Initially, Gojong and the Joseon government shared this belief and agreed to collaborate with the Japanese military.[22] Korean intellectuals had predicted that the victor of the Russo-Japanese War would assume hegemony over their peninsula, and as an Asian power, Japan enjoyed greater public support in Korea than did Russia. However, policies such as land confiscation and the drafting of forced labor turned popular opinion against the Japanese, a trend exacerbated by the arrest or execution of those who resisted.[22] Ironically, An Jung-geun was also a proponent of what would later come to be called Pan-Asianism. He believed in a union of the three East Asian nations in order to repel the "White Peril"[15] of Western imperialism and restore peace in the region.

Genealogy

Hayashi family

Itō family

Honours

From the Japanese Wikipedia article

Japanese

Peerages

Count (July 7, 1884)

Marquis (August 5, 1895)

Prince (September 21, 1907)

Decorations

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_1Class_BAR.svg/50px-JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_1Class_BAR.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_1Class_BAR.svg/75px-JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_1Class_BAR.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_1Class_BAR.svg/100px-JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_1Class_BAR.svg.png 2x|ribbon bar|h14|w50]] Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (November 2, 1877)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_Paulownia_BAR.svg/50px-JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_Paulownia_BAR.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_Paulownia_BAR.svg/75px-JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_Paulownia_BAR.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_Paulownia_BAR.svg/100px-JPN_Kyokujitsu-sho_Paulownia_BAR.svg.png 2x|JPN Kyokujitsu-sho Paulownia BAR.svg|h14|w50]] Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (February 11, 1889)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg/50px-JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg/75px-JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg/100px-JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg.png 2x|JPN Daikun'i kikkasho BAR.svg|h14|w50]] Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (August 5, 1895)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg/50px-JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg/75px-JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg/100px-JPN_Daikun%27i_kikkasho_BAR.svg.png 2x|JPN Daikun'i kikkasho BAR.svg|h14|w50]] Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (April 1, 1906)

Court ranks

Fifth rank, junior grade (1868)

Fifth rank (1869)

Fourth rank (1870)

Senior fourth rank (February 18. 1874)

Third rank (December 27, 1884)

Second rank (October 19, 1886)

Senior second rank (December 20, 1895)

Junior First Rank (October 26, 1909; posthumous)

Foreign

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Flag_of_the_German_Empire.svg/23px-Flag_of_the_German_Empire.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Flag_of_the_German_Empire.svg/35px-Flag_of_the_German_Empire.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Flag_of_the_German_Empire.svg/45px-Flag_of_the_German_Empire.svg.png 2x|German Empire|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] German Empire Order of the White Falcon, 1st Class of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (September 29, 1882) [[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg/23px-Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg/35px-Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg/46px-Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg.png 2x|Kingdom of Prussia|h14|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] Order of the Crown, 1st Class of Prussia (1886) [[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg/23px-Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg/35px-Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg/46px-Flag_of_Prussia_%281892-1918%29.svg.png 2x|Kingdom of Prussia|h14|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of the Red Eagle of Prussia (December 22, 1886) (he later received the Grand Cross in brilliants during his visit to Berlin in December 1901[23])

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Flag_of_Russia.svg/23px-Flag_of_Russia.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Flag_of_Russia.svg/35px-Flag_of_Russia.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Flag_of_Russia.svg/45px-Flag_of_Russia.svg.png 2x|Russian Empire|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of the White Eagle of the Russian Empire (September 17, 1883)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/4/4c/Flag_of_Sweden.svg/23px-Flag_of_Sweden.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/4/4c/Flag_of_Sweden.svg/35px-Flag_of_Sweden.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/4/4c/Flag_of_Sweden.svg/46px-Flag_of_Sweden.svg.png 2x|Sweden|h14|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of Vasa of Sweden (May 25, 1885)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_%281869-1918%29.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_%281869-1918%29.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_%281869-1918%29.svg/35px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_%281869-1918%29.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_%281869-1918%29.svg/45px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_%281869-1918%29.svg.png 2x|Austria-Hungary|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of the Iron Crown of Austria-Hungary (September 27, 1885)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/9/9a/Flag_of_Spain.svg/23px-Flag_of_Spain.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/9/9a/Flag_of_Spain.svg/35px-Flag_of_Spain.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/9/9a/Flag_of_Spain.svg/45px-Flag_of_Spain.svg.png 2x|Spain|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of Charles III of Spain (October 26, 1896)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Flag_of_Belgium_%28civil%29.svg/23px-Flag_of_Belgium_%28civil%29.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Flag_of_Belgium_%28civil%29.svg/35px-Flag_of_Belgium_%28civil%29.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Flag_of_Belgium_%28civil%29.svg/45px-Flag_of_Belgium_%28civil%29.svg.png 2x|Belgium|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of Leopold of Belgium (October 4, 1897)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/c/c3/Flag_of_France.svg/23px-Flag_of_France.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/c/c3/Flag_of_France.svg/35px-Flag_of_France.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/c/c3/Flag_of_France.svg/45px-Flag_of_France.svg.png 2x|France|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Legion d'Honneur of France (April 29, 1898)

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Flag_of_Russia.svg/23px-Flag_of_Russia.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Flag_of_Russia.svg/35px-Flag_of_Russia.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Flag_of_Russia.svg/45px-Flag_of_Russia.svg.png 2x|Russian Empire|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] GC of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky of Russia (November 28, 1901)[24]

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/a/ae/Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg/23px-Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/a/ae/Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg/35px-Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/a/ae/Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg/46px-Flag_of_the_United_Kingdom.svg.png 2x|United Kingdom|h12|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB), United Kingdom (January 14, 1902; after a visit to London)[25]

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Flag_of_Italy_%281861-1946%29_crowned.svg/23px-Flag_of_Italy_%281861-1946%29_crowned.svg.png|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Flag_of_Italy_%281861-1946%29_crowned.svg/35px-Flag_of_Italy_%281861-1946%29_crowned.svg.png 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Flag_of_Italy_%281861-1946%29_crowned.svg/45px-Flag_of_Italy_%281861-1946%29_crowned.svg.png 2x|Kingdom of Italy|h15|w23|thumbborder flagicon-img flagicon-img]] Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation of Italy (January 16, 1902; during his visit to Rome)[26]

Popular culture

Portrayed by Kim In-woo in the 2018 tvN and Netflix TV series Mr. Sunshine.

See also

Japanese students in Britain