Depreciation

Depreciation

In accountancy, depreciation refers to two aspects of the same concept: first, the actual decrease in value of fair value of an asset, such as the decrease in value of factory equipment each year as it is used and wears, and second, the allocation in accounting statements of the original cost of the assets to periods in which the assets are used (depreciation with the matching principle).[1]

Depreciation is thus the decrease in the value of assets and the method used to reallocate, or "write down" the cost of a tangible asset (such as equipment) over its useful life span. Businesses depreciate long-term assets for both accounting and tax purposes.The decrease in value of the asset affects the balance sheet of a business or entity, and the method of depreciating the asset, accounting-wise, affects the net income, and thus the income statement that they report. Generally the cost is allocated as depreciation expense among the periods in which the asset is expected to be used.

Methods of computing depreciation, and the periods over which assets are depreciated, may vary between asset types within the same business and may vary for tax purposes. These may be specified by law or accounting standards, which may vary by country. There are several standard methods of computing depreciation expense, including fixed percentage, straight line, and declining balance methods. Depreciation expense generally begins when the asset is placed in service. For example, a depreciation expense of 100 per year for five years may be recognized for an asset costing 500. Depreciation has been defined as the diminution in the utility or value of an asset, and is a non cash expense. It does not result in any cash outflow; it just means that the asset is not worth as much as it used to be. Causes of depreciation are natural wear and tear.

Accounting concept

In determining the profits (net income) from an activity, the receipts from the activity must be reduced by appropriate costs. One such cost is the cost of assets used but not immediately consumed in the activity.[2] Such cost allocated in a given period is equal to the reduction in the value placed on the asset, which is initially equal to the amount paid for the asset and subsequently may or may not be related to the amount expected to be received upon its disposal. Depreciation is any method of allocating such net cost to those periods in which the organization is expected to benefit from use of the asset. The asset is referred to as a depreciable asset. Depreciation is technically a method of allocation, not valuation,[3] even though it determines the value placed on the asset in the balance sheet.

Any business or income producing activity[4] using tangible assets may incur costs related to those assets. If an asset is expected to produce a benefit in future periods, some of these costs must be deferred rather than treated as a current expense. The business then records depreciation expense in its financial reporting as the current period's allocation of such costs. This is usually done in a rational and systematic manner. Generally this involves four criteria:

Cost of the asset

Expected salvage value, also known as residual value of the assets

Estimated useful life of the asset

A method of apportioning the cost over such life[5]

Depreciable basis

Cost generally is the amount paid for the asset, including all costs related to acquisition.[6] In some countries or for some purposes, salvage value may be ignored. The rules of some countries specify lives and methods to be used for particular types of assets. However, in most countries the life is based on business experience, and the method may be chosen from one of several acceptable methods.

Impairment

Accounting rules also require that an impairment charge or expense be recognized if the value of assets declines unexpectedly.[7] Such charges are usually nonrecurring, and may relate to any type of asset. Many companies consider write-offs of some of their long-lived assets because some property, plant, and equipment have suffered partial obsolescence. Accountants reduce the asset's carrying amount by its fair value. For example, if a company continues to incur losses because prices of a particular product or service are higher than the operating costs, companies consider write-offs of the particular asset. These write-offs are referred to as impairments. There are events and changes in circumstances might lead to impairment. Some examples are:

Large amount of decrease in fair value of an asset

A change of manner in which the asset is used

Accumulation of costs that are not originally expected to acquire or construct an asset

A projection of incurring losses associated with the particular asset

Events or changes in circumstances indicate that the company may not be able recover the carrying amount of the asset. In which case, companies use the recoverability test to determine whether impairment has occurred. The steps to determine are:

- Estimate the future cash flow of asset (from the use of the asset to disposition)

- If the sum of the expected cash flow is less than the carrying amount of the asset, the asset is considered impaired

Depletion and amortization

Depletion and amortization are similar concepts for minerals (including oil) and intangible assets, respectively.

Effect on cash

Depreciation expense does not require current outlay of cash. However, since depreciation is an expense to the P&L account, provided the enterprise is operating in a manner that covers its expenses (e.g. operating at a profit) depreciation is a source of cash in a statement of cash flows, which generally offsets the cash cost of acquiring new assets required to continue operations when existing assets reach the end of their useful lives.

Accumulated depreciation

While depreciation expense is recorded on the income statement of a business, its impact is generally recorded in a separate account and disclosed on the balance sheet as accumulated under fixed assets, according to most accounting principles. Accumulated depreciation is known as a contra account, because it separately shows a negative amount that is directly associated an accumulated depreciation account on the balance sheet, depreciation expense is usually charged against the relevant asset directly. The values of the fixed assets stated on the balance sheet will decline, even if the business has not invested in or disposed of any assets. The amounts will roughly approximate fair value. Otherwise, depreciation expense is charged against accumulated depreciation. Showing accumulated depreciation separately on the balance sheet has the effect of preserving the historical cost of assets on the balance sheet. If there have been no investments or dispositions in fixed assets for the year, then the values of the assets will be the same on the balance sheet for the current and prior year (P/Y).

Methods for depreciation

There are several methods for calculating depreciation, generally based on either the passage of time or the level of activity (or use) of the asset.

Straight-line depreciation

Straight-line depreciation is the simplest and most often used method. In this method, the company estimates the residual value (also known as salvage value or scrap value) of the asset at the end of the period during which it will be used to generate revenues (useful life). (The salvage value may be zero, or even negative due to costs required to retire it; however, for depreciation purposes salvage value is not generally calculated at below zero.) The company will then charge the same amount to depreciation each year over that period, until the value shown for the asset has reduced from the original cost to the salvage value.

Straight-line method:

For example, a vehicle that depreciates over 5 years is purchased at a cost of $17,000, and will have a salvage value of $2000. Then this vehicle will depreciate at $3,000 per year, i.e. (17-2)/5 = 3. This table illustrates the straight-line method of depreciation. Book value at the beginning of the first year of depreciation is the original cost of the asset. At any time book value equals original cost minus accumulated depreciation.

book value = original cost − accumulated depreciation Book value at the end of year becomes book value at the beginning of next year. The asset is depreciated until the book value equals scrap value.

| Depreciation expense | Accumulated depreciation at year-end | Book value at year-end |

|---|---|---|

| (original cost) $17,000 | ||

| $3,000 | $3,000 | $14,000 |

| 3,000 | 6,000 | 11,000 |

| 3,000 | 9,000 | 8,000 |

| 3,000 | 12,000 | 5,000 |

| 3,000 | 15,000 | (scrap value) 2,000 |

If the vehicle were to be sold and the sales price exceeded the depreciated value (net book value) then the excess would be considered a gain and subject to depreciation recapture. In addition, this gain above the depreciated value would be recognized as ordinary income by the tax office. If the sales price is ever less than the book value, the resulting capital loss is tax deductible. If the sale price were ever more than the original book value, then the gain above the original book value is recognized as a capital gain.

If a company chooses to depreciate an asset at a different rate from that used by the tax office then this generates a timing difference in the income statement due to the difference (at a point in time) between the taxation department's and company's view of the profit.

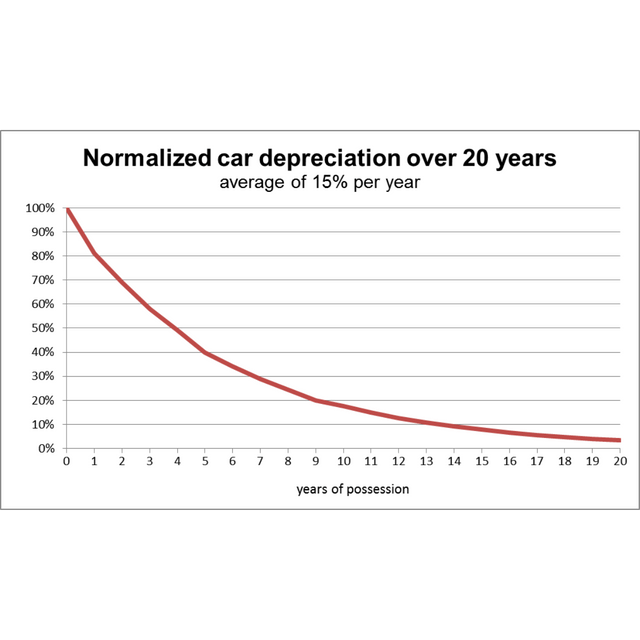

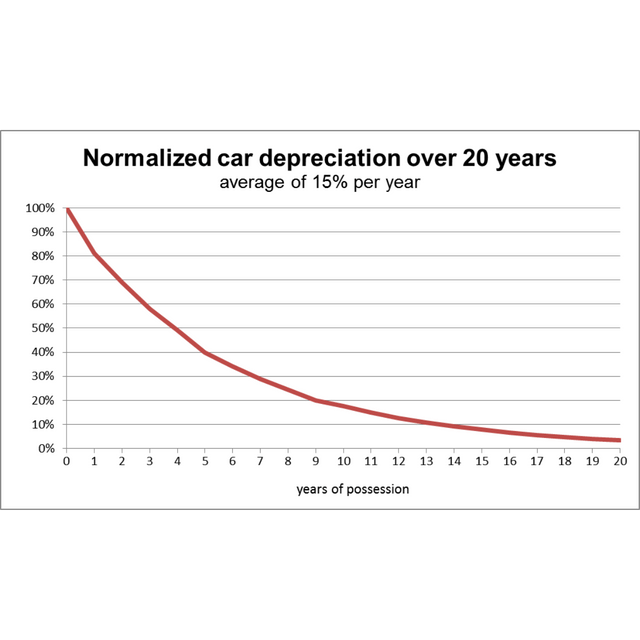

In the UK used car pricing expert CAP regularly examine their data to find vehicles that devalue at a slower rate than others. They discuss the distinction and differences between percentage depreciate figures and real world cash depreciation to help motorists to reduce their long term costs.[8] When buying a new vehicle it is important to consider if you are likely to change the car in the next three years (when most cars lose between 50% and 60% of their value[9]) and the expected future value (also known as residual value). For example: "If you buy a car for £8,000 which 5 years later is only worth £2,000 you are actually going to have less value than if you had purchased a vehicle for £10,000 that 5 years later is worth £5,000.[10]

Diminishing balance method

| Depreciation rate | Depreciation expense | Accumulated depreciation | Book value at year-end |

|---|---|---|---|

| original cost $1,000.00 | |||

| 40% | 400.00 | 400.00 | 600.00 |

| 40% | 240.00 | 640.00 | 360.00 |

| 40% | 144.00 | 784.00 | 216.00 |

| 40% | 86.40 | 870.40 | 129.60 |

| 129.60 - 100.00 | 29.60 | 900.00 | scrap value 100.00 |

When using the double-declining-balance method, the salvage value is not considered in determining the annual depreciation, but the book value of the asset being depreciated is never brought below its salvage value, regardless of the method used. Depreciation ceases when either the salvage value or the end of the asset's useful life is reached.

Since double-declining-balance depreciation does not always depreciate an asset fully by its end of life, some methods also compute a straight-line depreciation each year, and apply the greater of the two. This has the effect of converting from declining-balance depreciation to straight-line depreciation at a midpoint in the asset's life.

With the declining balance method, one can find the depreciation rate that would allow exactly for full depreciation by the end of the period, using the formula:

![\mbox{depreciation rate} = 1 - \sqrt[N]{\mbox{residual value} \over \mbox{cost of fixed asset}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/008d7dd3c2a6dde1d1063b2dba1a0af91949e524) ,

,where N is the estimated life of the asset (for example, in years).

Annuity depreciation

Annuity depreciation methods are not based on time, but on a level of Annuity. This could be miles driven for a vehicle, or a cycle count for a machine. When the asset is acquired, its life is estimated in terms of this level of activity. Assume the vehicle above is estimated to go 50,000 miles in its lifetime. The per-mile depreciation rate is calculated as: ($17,000 cost - $2,000 salvage) / 50,000 miles = $0.30 per mile. Each year, the depreciation expense is then calculated by multiplying the number of miles driven by the per-mile depreciation rate..

Sum-of-years-digits method

Sum-of-years-digits is a shent depreciation method that results in a more accelerated write-off than the straight line method, and typically also more accelerated than the declining balance method. Under this method the annual depreciation is determined by multiplying the depreciable cost by a schedule of fractions.

Sum of the years' digits method of depreciation is one of the accelerated depreciation techniques which are based on the assumption that assets are generally more productive when they are new and their productivity decreases as they become old. The formula to calculate depreciation under SYD method is:

SYD depreciation = depreciable base x (remaining useful life/sum of the years' digits)

depreciable base = cost − salvage value

Example: If an asset has original cost of $1000, a useful life of 5 years and a salvage value of $100, compute its depreciation schedule.

First, determine years' digits. Since the asset has useful life of 5 years, the years' digits are: 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1.

Next, calculate the sum of the digits: 5+4+3+2+1=15

The sum of the digits can also be determined by using the formula (n2+n)/2 where n is equal to the useful life of the asset in years. The example would be shown as (52+5)/2=15

Depreciation rates are as follows:

5/15 for the 1st year, 4/15 for the 2nd year, 3/15 for the 3rd year, 2/15 for the 4th year, and 1/15 for the 5th year.

| Depreciable base | Depreciation rate | Depreciation expense | Accumulated depreciation | Book value at end of year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $1,000 (original cost) | ||||

| 900 | 5/15 | 300 =(900 x 5/15) | 300 | 700 |

| 900 | 4/15 | 240 =(900 x 4/15) | 540 | 460 |

| 900 | 3/15 | 180 =(900 x 3/15) | 720 | 280 |

| 900 | 2/15 | 120 =(900 x 2/15) | 840 | 160 |

| 900 | 1/15 | 60 =(900 x 1/15) | 900 | 100 (scrap value) |

Units-of-production depreciation method

Under the units-of-production method, useful life of the asset is expressed in terms of the total number of units expected to be produced:

Suppose, an asset has original cost $70,000, salvage value $10,000, and is expected to produce 6,000 units.

Depreciation per unit = ($70,000−10,000) / 6,000 = $10

10 × actual production will give the depreciation cost of the current year.

The table below illustrates the units-of-production depreciation schedule of the asset.

| Units of production | Depreciation cost per unit | Depreciation expense | Accumulated depreciation | Book value at year-end |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $70,000 (original cost) | ||||

| 1,000 | 10 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 60,000 |

| 1,100 | 10 | 11,000 | 21,000 | 49,000 |

| 1,200 | 10 | 12,000 | 33,000 | 37,000 |

| 1,300 | 10 | 13,000 | 46,000 | 24,000 |

| 1,400 | 10 | 14,000 | 60,000 | 10,000 (scrap value) |

Depreciation stops when book value is equal to the scrap value of the asset. In the end, the sum of accumulated depreciation and scrap value equals the original cost.

Group depreciation method

The group depreciation method is used for depreciating multiple-asset accounts using a similar depreciation method. The assets must be similar in nature and have approximately the same useful lives.

Composite depreciation method

The composite method is applied to a collection of assets that are not similar, and have different service lives. For example, computers and printers are not similar, but both are part of the office equipment. Depreciation on all assets is determined by using the straight-line-depreciation method.

| Asset | Historical cost | Salvage value | Depreciable cost | Life | Depreciation per year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computers | $5,500 | $500 | $5,000 | 5 | $1,000 |

| Printers | $1,000 | $100 | $900 | 3 | $300 |

| Total | $6,500 | $600 | $5,900 | 4.5 | $1,300 |

Composite life equals the total depreciable cost divided by the total depreciation per year. $5,900 / $1,300 = 4.5 years.

Composite depreciation rate equals depreciation per year divided by total historical cost. $1,300 / $6,500 = 0.20 = 20%

Depreciation expense equals the composite depreciation rate times the balance in the asset account (historical cost). (0.20 * $6,500) $1,300. Debit depreciation expense and credit accumulated depreciation.

When an asset is sold, debit cash for the amount received and credit the asset account for its original cost. Debit the difference between the two to accumulated depreciation. Under the composite method no gain or loss is recognized on the sale of an asset. Theoretically, this makes sense because the gains and losses from assets sold before and after the composite life will average themselves out.

To calculate composite depreciation rate, divide depreciation per year by total historical cost. To calculate depreciation expense, multiply the result by the same total historical cost. The result, not surprisingly, will equal to the total depreciation per year again.

Common sense requires depreciation expense to be equal to total depreciation per year, without first dividing and then multiplying total depreciation per year by the same number.

Tax depreciation

Most income tax systems allow a tax deduction for recovery of the cost of assets used in a business or for the production of income. Such deductions are allowed for individuals and companies. Where the assets are consumed currently, the cost may be deducted currently as an expense or treated as part of cost of goods sold. The cost of assets not currently consumed generally must be deferred and recovered over time, such as through depreciation. Some systems permit full deduction of the cost, at least in part, in the year the assets are acquired. Other systems allow depreciation expense over some life using some depreciation method or percentage. Rules vary highly by country, and may vary within a country based on type of asset or type of taxpayer. Many systems that specify depreciation lives and methods for financial reporting require the same lives and methods be used for tax purposes. Most tax systems provide different rules for real property (buildings, etc.) and personal property (equipment, etc.).

Capital allowances

A common system is to allow a fixed percentage of the cost of depreciable assets to be deducted each year. This is often referred to as a capital allowance, as it is called in the United Kingdom. Deductions are permitted to individuals and businesses based on assets placed in service during or before the assessment year. Canada's Capital Cost Allowance are fixed percentages of assets within a class or type of asset. Fixed percentage rates are specified by type of asset. The fixed percentage is multiplied by the tax basis of assets in service to determine the capital allowance deduction. The tax law or regulations of the country specifies these percentages. Capital allowance calculations may be based on the total set of assets, on sets or pools by year (vintage pools) or pools by classes of assets... Depreciation has got three methods only.

Tax lives and methods

Some systems specify lives based on classes of property defined by the tax authority. Canada Revenue Agency specifies numerous classes [24] based on the type of property and how it is used. Under the United States depreciation system, the Internal Revenue Service publishes a detailed guide [25] which includes a table of asset lives and the applicable conventions. The table also incorporates specified lives for certain commonly used assets (e.g., office furniture, computers, automobiles) which override the business use lives. U.S. tax depreciation is computed under the double declining balance method switching to straight line or the straight line method, at the option of the taxpayer.[11] IRS tables specify percentages to apply to the basis of an asset for each year in which it is in service. Depreciation first becomes deductible when an asset is placed in service.

Additional depreciation

Many systems allow an additional deduction for a portion of the cost of depreciable assets acquired in the current tax year. The UK system provides a first year capital allowance of £50,000. In the United States, two such deductions are available. A deduction [26] for the full cost of depreciable tangible personal property is allowed up to $500,000 through 2013. This deduction is fully phased out for businesses acquiring over $2,000,000 of such property during the year.[12] In addition, additional first year depreciation of 50% of the cost of most other depreciable tangible personal property is allowed as a deduction.[13] Some other systems have similar first year or accelerated allowances.

Real property

Many tax systems prescribe longer depreciable lives for buildings and land improvements. Such lives may vary by type of use. Many such systems, including the United States and Canada, permit depreciation for real property using only the straight line method, or a small fixed percentage of cost. Generally, no depreciation tax deduction is allowed for bare land. In the United States, residential rental buildings are depreciable over a 27.5 year or 40 year life, other buildings over a 39 or 40 year life, and land improvements over a 15 or 20 year life, all using the straight line method.[14]

Averaging conventions

Depreciation calculations require a lot of record-keeping if done for each asset a business owns, especially if assets are added to after they are acquired, or partially disposed of. However, many tax systems permit all assets of a similar type acquired in the same year to be combined in a "pool". Depreciation is then computed for all assets in the pool as a single calculation. These calculations must make assumptions about the date of acquisition. The United States system allows a taxpayer to use a half year convention for personal property or mid-month convention for real property.[15] Under such a convention, all property of a particular type is considered to have been acquired at the midpoint of the acquisition period. One half of a full period's depreciation is allowed in the acquisition period (and also in the final depreciation period if the life of the assets is a whole number of years). United States rules require a mid-quarter convention for per property if more than 40% of the acquisitions for the year are in the final quarter..

Economics

See also

Amortization

Construction in progress

Consumption of fixed capital

Cost segregation study

Deferred financing costs

Deferred tax

Depletion (accounting)

Expense

John I. Beggs

MACRS

Revaluation of fixed assets

Writing down allowance