Bhikkhu

Bhikkhu

| Bhikkhu | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 比丘 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Native Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 和尚 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||||

| Burmese | ဘိက္ခု | ||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | དགེ་སློང་ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Tỉ-khâu | ||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||

| Thai | ภิกษุ | ||||||||

| RTGS | phiksu | ||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 僧、比丘 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tamil name | |||||||||

| Tamil | துறவி tuṟavi | ||||||||

| Sanskrit name | |||||||||

| Sanskrit | भिक्षु (Bhikṣu) | ||||||||

| Pali name | |||||||||

| Pali | Bhikkhu | ||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||

| Khmer | ភិក្ខុ (Phikkhok) | ||||||||

| Nepali name | |||||||||

| Nepali | भिक्षु | ||||||||

| Sinhala name | |||||||||

| Sinhala | භික්ෂුව | ||||||||

| Telugu name | |||||||||

| Telugu | భిక్షువు bhikṣuvu | ||||||||

A person under the age of 20 cannot be ordained as a bhikkhu or bhikkhuni but can be ordained as a śrāmaṇera or śrāmaṇērī.

| Bhikkhu | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 比丘 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Native Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 和尚 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Burmese name | |||||||||

| Burmese | ဘိက္ခု | ||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

| Tibetan | དགེ་སློང་ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Tỉ-khâu | ||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||

| Thai | ภิกษุ | ||||||||

| RTGS | phiksu | ||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 僧、比丘 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Tamil name | |||||||||

| Tamil | துறவி tuṟavi | ||||||||

| Sanskrit name | |||||||||

| Sanskrit | भिक्षु (Bhikṣu) | ||||||||

| Pali name | |||||||||

| Pali | Bhikkhu | ||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||

| Khmer | ភិក្ខុ (Phikkhok) | ||||||||

| Nepali name | |||||||||

| Nepali | भिक्षु | ||||||||

| Sinhala name | |||||||||

| Sinhala | භික්ෂුව | ||||||||

| Telugu name | |||||||||

| Telugu | భిక్షువు bhikṣuvu | ||||||||

Definition

Bhikkhu literally means "beggar" or "one who lives by alms".[4] The historical Buddha, Prince Siddhartha, having abandoned a life of pleasure and status, lived as an alms mendicant as part of his śramaṇa lifestyle. Those of his more serious students who renounced their lives as householders and came to study full-time under his supervision also adopted this lifestyle. These full-time student members of the sangha became the community of ordained monastics who wandered from town to city throughout the year, living off alms and stopping in one place only for the Vassa, the rainy months of the monsoon season.

[266-267] He is not a monk just because he lives on others' alms. Not by adopting outward form does one become a true monk. Whoever here (in the Dispensation) lives a holy life, transcending both merit and demerit, and walks with understanding in this world — he is truly called a monk.

Historical terms in Western literature

A bonze farmer

In English literature before the mid-20th century, Buddhist monks were often referred to by the term bonze, particularly when describing monks from East Asia and French Indochina. This term is derived Portuguese and French from Japanese bonsō, meaning 'priest, monk'. It is rare in modern literature.[7]

Buddhist monks were once called talapoy or talapoin from French talapoin, itself from Portuguese talapão, ultimately from Mon tala pōi, meaning 'our lord'.[8][9]

The Talapoys cannot be engaged in any of the temporal concerns of life; they must not trade or do any kind of manual labour, for the sake of a reward; they are not allowed to insult the earth by digging it. Having no tie, which unites their interests with those of the people, they are ready, at all times, with spiritual arms, to enforce obedience to the will of the sovereign.— Edmund Roberts, Embassy to the eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat[10]

The talapoin is a monkey named after Buddhist monks just as the capuchin monkey is named after the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (who also are the origin of the word cappuccino).

Ordination

Theravada

Theravada monasticism is organized around the guidelines found within a division of the Pāli Canon called the Vinaya Pitaka. Laypeople undergo ordination as a novitiate (śrāmaṇera or sāmanera) in a rite known as the "going forth" (Pali: pabbajja). Sāmaneras are subject to the Ten Precepts. From there full ordination (Pali: upasampada) may take place. Bhikkhus are subject to a much longer set of rules known as the Pātimokkha (Theravada) or Prātimokṣa (Mahayana and Vajrayana).

Mahayana

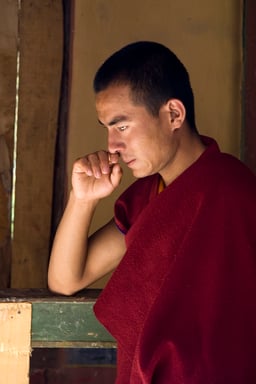

Tibetan monks engaging in a traditional monastic debate.

In the Mahayana monasticism is part of the system of "vows of individual liberation".[5] These vows are taken by monks and nuns from the ordinary sangha, in order to develop personal ethical discipline.[5] In Mahayana and Vajrayana, the term "sangha" is, in principle, often understood to refer particularly to the aryasangha (Wylie: mchog kyi tshogs), the "community of the noble ones who have reached the first bhūmi". These, however, need not be monks and nuns.

The vows of individual liberation are taken in four steps. A lay person may take the five upāsaka and upāsikā vows (Wylie: dge snyan (ma) "approaching virtue"). The next step is to enter the pabbajja or monastic way of life (Skt: pravrajyā, Wylie: rab byung), which includes wearing monk's or nun's robes. After that, one can become a samanera or samaneri "novice" (Skt. śrāmaṇera, śrāmaṇeri, Wylie: dge tshul, dge tshul ma). The last and final step is to take all the vows of a bhikkhu or bhukkhuni "fully ordained monastic" (Sanskrit: bhikṣu, bhikṣuṇī, Wylie: dge long (ma)).

Monastics take their vows for life but can renounce them and return to non-monastic life[11] and even take the vows again later.[11] A person can take them up to three times or seven times in one life, depending on the particular practices of each school of discipline; after that, the sangha should not accept them again.[12] In this way, Buddhism keeps the vows "clean". It is possible to keep them or to leave this lifestyle, but it is considered extremely negative to break these vows.

In Tibet, the upāsaka, pravrajyā and bhikṣu ordinations are usually taken at ages six, fourteen and twenty-one or older, respectively.

Robes

A Cambodian monk in his robes

Two monks in orange robes

The special dress of ordained people, referred to in English as robes, comes from the idea of wearing a simple durable form of protection for the body from weather and climate. In each tradition there is uniformity in the colour and style of dress. Colour is often chosen due to the wider availability of certain pigments in a given geographical region. In Tibet and the Himalayan regions (Kashmir, Nepal and Bhutan) red is the preferred pigment used in the dying of robes. In Burma, reddish brown; In India, Sri Lanka and South-East Asia various shades of yellow, ochre and orange prevail. In China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam grey or black is common. Monks often make their own robes from cloth that is donated to them.[1]

The robes of Tibetan novices and monks differ in various aspects, especially in the application of "holes" in the dress of monks. Some monks tear their robes into pieces and then mend these pieces together again. Upāsakas cannot wear the "chö-göö", a yellow tissue worn during teachings by both novices and full monks.

In observance of the Kathina Puja, a special Kathina robe is made in 24 hours from donations by lay supporters of a temple. The robe is donated to the temple or monastery, and the resident monks then select from their own number a single monk to receive this special robe.[13]

Additional vows in the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions

In Mahayana traditions, a Bhikṣu may take additional vows not related to ordination, including the Bodhisattva vows, samaya vows, and others, which are also open to laypersons in most instances.

Japan and Korea

Saichō believed the 250 precepts were for the Śrāvakayāna and that ordination should use the Mahayana precepts of the Brahmajala Sutra. He stipulated that monastics remain on Mount Hiei for twelve years of isolated training and follow the major themes of the 250 precepts: celibacy, non-harming, no intoxicants, vegetarian eating and reducing labor for gain. After twelve years, monastics would then use the Vinaya precepts as a provisional, or supplemental, guideline to conduct themselves by when serving in non-monastic communities.[14] Tendai monastics followed this practice.

During Japan's Meiji Restoration during the 1870s, the government abolished celibacy and vegetarianism for Buddhist monastics in an effort to secularise them and promote the newly created State Shinto.[15][16] Japanese Buddhists won the right to proselytize inside cities, ending a five-hundred year ban on clergy members entering cities.[17]

Currently, priests (lay religious leaders) in Japan choose to observe vows as appropriate to their family situation. Celibacy and other forms of abstaining are generally "at will" for varying periods of time.

After the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, when Japan annexed Korea, Korean Buddhism underwent many changes. Jōdo Shinshū and Nichiren schools began sending missionaries to Korea under Japanese rule, and new sects formed there such as Won Buddhism. The Temple Ordinance of 1911 (Korean: 사찰령; Hanja: 寺刹令) changed the traditional system whereby temples were run as a collective enterprise by the Sangha, replacing this system with Japanese-style management practices in which temple abbots appointed by the Governor-General of Korea were given private ownership of temple property and given the rights of inheritance to such property.[18] More importantly, monks from pro-Japanese factions began to adopt Japanese practices, by marrying and having children.[18]

In Korea, the practice of celibacy varies. The two sects of Korean Seon divided in 1970 over this issue; the Jogye Order is fully celibate while the Taego Order has both celibate monastics and non-celibate Japanese-style priests.