Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn

Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn

Bedford–Stuyvesant | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Brooklyn | |

| Nickname(s): Bed-Stuy | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates:40°41′13″N 73°56′28″W [146] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | |

| Borough | |

| Community District | Brooklyn 3,[1] Brooklyn 8[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.21 km2(2.782 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[3] | |

| • Total | 157,530 |

| • Density | 22,000/km2(57,000/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Black | 49% |

| • White | 27% |

| • Hispanic | 19% |

| • Asian | 3% |

| • Others | 2% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $51,907 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 11205, 11206, 11216, 11221, 11233, 11238 |

| Area code | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

Stuyvesant Heights Historic District | |

U.S. Historic district | |

On Decatur Street | |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Macon, Tompkins, Decatur, Lewis, Chauncey, and Stuyvesant, New York, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°40′52″N 73°56′14″W [147] |

| Area | 42 acres (17 ha) |

| Built | 1870 |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Queen Anne, Romanesque |

| NRHP reference # | 75001193 [148] [53] |

Stuyvesant Heights Historic District (Boundary Increase) | |

U.S. Historic district | |

| Location | Roughly, Decatur St. from Tompkins to Lewis Aves., Brooklyn, New York |

| Area | 10 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Architect | multiple |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Second Empire, Queen Anne |

| NRHP reference # | 96001355 [149] [53] |

| Added to NRHP | November 15, 1996 |

| Added to NRHP | December 4, 1975 |

Bedford–Stuyvesant (/ˈbɛdfərdˈstaɪvəsənt/; colloquially known as Bed–Stuy[5]) is a neighborhood in the north-central portion of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. Bedford–Stuyvesant is bordered by Flushing Avenue to the north (bordering Williamsburg), Classon Avenue to the west (bordering Clinton Hill), Broadway to the east (bordering Bushwick and East New York), and Atlantic Avenue to the south (bordering Crown Heights and Brownsville).[6] The main shopping street, Fulton Street runs east–west the length of the neighborhood and intersects high-traffic north-south streets including Bedford Avenue, Nostrand Avenue, and Stuyvesant Avenue. Bedford–Stuyvesant contains four smaller neighborhoods: Bedford, Stuyvesant Heights, Ocean Hill, and Weeksville (also part of Crown Heights). Part of Clinton Hill was once considered part of Bedford–Stuyvesant.

Bedford–Stuyvesant is renowned for its collection of intact and largely untouched Victorian architecture, the largest in the country, with roughly 8,800 buildings built before 1900.[7] Its building stock includes many historic brownstones. These homes were developed for the expanding middle- to upper-middle class from the 1890s to the late 1910s. They contain highly ornamental detailing throughout their interiors and have classical architectural elements, such as brackets, quoins, fluting, finials, and elaborate frieze and cornice banding.

Since late 1930's the neighborhood has been a major cultural center for Brooklyn's African American population. Following the construction of the Fulton Street subway line (A and C trains)[8] in 1936, African Americans left an overcrowded Harlem for greater housing availability in Bedford–Stuyvesant. From Bedford–Stuyvesant, African Americans have since moved into the surrounding areas of Brooklyn, such as East New York, Crown Heights, Brownsville, and Fort Greene.

Bedford–Stuyvesant is mostly part of Brooklyn Community District 3, though a small part is also in Community District 8. Its primary ZIP Codes are 11205, 11206, 11216, 11221, 11233, and 11238.[1][2] Bedford–Stuyvesant is patrolled by the 79th and 84th Precincts of the New York City Police Department.[9][10] Politically it is represented by the New York City Council's 36th District.

Bedford–Stuyvesant | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Brooklyn | |

| Nickname(s): Bed-Stuy | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates:40°41′13″N 73°56′28″W [146] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | |

| Borough | |

| Community District | Brooklyn 3,[1] Brooklyn 8[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.21 km2(2.782 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[3] | |

| • Total | 157,530 |

| • Density | 22,000/km2(57,000/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Black | 49% |

| • White | 27% |

| • Hispanic | 19% |

| • Asian | 3% |

| • Others | 2% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $51,907 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 11205, 11206, 11216, 11221, 11233, 11238 |

| Area code | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

Stuyvesant Heights Historic District | |

U.S. Historic district | |

On Decatur Street | |

| Location | Roughly bounded by Macon, Tompkins, Decatur, Lewis, Chauncey, and Stuyvesant, New York, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°40′52″N 73°56′14″W [147] |

| Area | 42 acres (17 ha) |

| Built | 1870 |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Queen Anne, Romanesque |

| NRHP reference # | 75001193 [148] [53] |

Stuyvesant Heights Historic District (Boundary Increase) | |

U.S. Historic district | |

| Location | Roughly, Decatur St. from Tompkins to Lewis Aves., Brooklyn, New York |

| Area | 10 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Architect | multiple |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Second Empire, Queen Anne |

| NRHP reference # | 96001355 [149] [53] |

| Added to NRHP | November 15, 1996 |

| Added to NRHP | December 4, 1975 |

History

Founding

The neighborhood's name combines the names of the Village of Bedford and the Stuyvesant Heights neighborhoods. Stuyvesant is derived from Peter Stuyvesant, the last governor of the colony of New Netherland.

17th and 18th centuries

In the second half of the 17th century, the lands which constitute the present neighborhood belonged to three Dutch settlers: Dirck Janse Hooghland, who operated a ferryboat on the East River, and farmers Jan Hansen, and Leffert Pietersen van Haughwout. In pre-revolutionary Kings County, Bedford was the first, major settlement east of the Village of Brooklyn on the ferry road to the town of Jamaica and eastern Long Island. Stuyvesant Heights, however, was farmland; the area became a community after the American Revolutionary War.

For most of its early history, Stuyvesant Heights was part of the outlying farm area of the small hamlet of Bedford, settled by the Dutch during the 17th century within the incorporated town of Breuckelen. The hamlet had its beginnings when a group of Breuckelen residents decided to improve their farm properties behind the Wallabout section, which gradually developed into an important produce center and market. The petition to form a new hamlet was approved by Governor Stuyvesant in 1663. Its leading signer was Thomas Lambertsen, a carpenter from Holland. A year later, the British capture of New Netherland signaled the end of Dutch rule. In Governor Nicolls' Charter of 1667 and in the Charter of 1686, Bedford is mentioned as a settlement within the Town of Brueckelen. Bedford hamlet had an inn as early as 1668, and, in 1670, the people of Breuckelen purchased from the Canarsie Indians an additional area for common lands in the surrounding region.

Bedford Corners, approximately located where the present Bedford Avenue meets Fulton Street, and only three blocks west of the present Historic District, was the intersection of several well traveled roads. The Brooklyn and Jamaica Turnpike, constructed by a corporation founded in 1809 and one of the oldest roads in Kings County, ran parallel to the present Fulton Street, from the East River ferry to the village of Brooklyn, thence to the hamlet of Bedford and on toward Jamaica via Bed–Stuy. Farmers from New Lots and Flatbush used this road on their way to Manhattan. Within the Stuyvesant Heights Historic District, the Turnpike ran along the approximate line of Decatur Street. Cripplebush Road to Newtown and the Clove Road to Flatbush also met at Bedford Corners. Hunterfly Road, which joined the Turnpike about a mile to the east of Clove Road, also served as a route for farmers and fishermen of the Canarsie and New Lots areas.

At the time of the Revolution, Leffert's son Jakop was a leading citizen of Bedford and the town clerk of Brooklyn. His neighbor, Lambert Suydam, was captain of the Kings County cavalry in 1776. An important part of the Battle of Long Island took place in and near the Historic District. In 1784, the people of the Town of Brooklyn held their first town meeting since 1776.

19th century

Row houses on MacDonough Street

Along Stuyvesant Avenue

Macon Street and Arlington Place

In 1800, Bedford was designated one of the seven districts of the Town of Brooklyn, and, in 1834, it became part of the seventh and ninth wards of the newly incorporated City of Brooklyn.

The present, gridiron, street system was laid out in 1835, as shown by the Street Commissioners map of 1839, and the blocks were lotted. The new street grid led to the abandonment of the Brooklyn and Jamaica Turnpike in favor of a continuation of Brooklyn's Fulton Street, which was opened up just south of the Historic District in 1842. The lands for the street system within what is now Bedford–Stuyvesant, however, were not sold to the City of Brooklyn until 1852. Earlier that year Charles C. Betts had purchased Maria Lott's tract of land. This marked the end of two centuries of Dutch patrimonial holdings. Betts, as Secretary of the Brooklyn Railroad Company acquired the land for the horsecar, later trolley, lines on Fulton Street and for investment purposes. Most of the streets were not actually opened, however, until the 1860s. Streets in Bedford–Stuyvesant were named after prominent figures in American history. Francis Lewis was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, whilst Bainbridge, Chauncey, Decatur and MacDonough were naval heroes of the Tripolitan War and the War of 1812. The Dripps Map of 1869 shows that the area was still largely rural with a few freestanding houses mostly on MacDonough Street. The real development of the district began slowly at first, accelerating between 1885 and 1900, and gradually tapering off during the first two decades of the 20th century.

In 1838, the Weeksville subsection was recognized as one of the first, free African-American communities in the United States.[11]

With the building of the Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad in 1833, along Atlantic Avenue, Bedford was established as a railroad station near the intersection of current Atlantic Avenue and Franklin Avenues. In 1836, the Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad was taken over by the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). In 1878, the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railway established its northern terminal with a connection to the LIRR at the same location.[12]

Construction of masonry row houses in the 1870s began to transform the rural district into an urban area. The first row of masonry houses in Stuyvesant Heights was built in 1872 on MacDonough Street for developer Curtis L. North. In the 1880s and 1890s, more rows were added, most of the Stuyvesant Heights north of Decatur Street looked much as it does today. Stuyvesant Heights was emerging as a neighborhood entity with its own distinctive characteristics. The houses had large rooms, high ceilings and large windows, and were built primarily by German immigrants.[13] The people who bought these houses were generally upper-middle-class families, mostly lawyers, shopkeepers, and merchants of German and Irish descent, with a sprinkling of English people; there were also a few professionals. A contemporary description calls it a very well kept residential neighborhood, typical of the general description of Brooklyn as "a town of homes and churches."

Built in 1863, the Capitoline Grounds were the home of the Brooklyn Atlantics baseball team.[14] The grounds were bordered by Nostrand Avenue, Halsey Street, Marcy Avenue, and Putnam Avenue.[14] During the winters, the operators would flood the area and open an ice-skating arena. The grounds were demolished in 1880.

In 1890, the city of Brooklyn founded another subsection Ocean Hill, a working-class predominantly Italian enclave.

In the last decades of the 19th century, with the advent of electric trolleys and the Fulton Street Elevated, Bedford–Stuyvesant became a working-class and middle-class bedroom community for those working in downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan in New York City. At that time, most of the pre-existing wooden homes were destroyed and replaced with brownstone rowhouses.

20th century

1900s to 1950s

In 1907, the completion of the Williamsburg Bridge facilitated the immigration of Jews and Italians from the Lower East Side of Manhattan.[15]

During the 1930s, major changes took place due to the Great Depression years. Immigrants from the American South and the Caribbean brought the neighborhood's black population to around 30,000, making it the second largest Black community in the city at the time. During World War II, the Brooklyn Navy Yard attracted many black New Yorkers to the neighborhood as an opportunity for employment, while the relatively prosperous war economy enabled many of the Jewish and Italian residents to move to Queens and Long Island. By 1950, the number of black residents had risen to 155,000, comprising about 55 percent of the population of Bedford–Stuyvesant.[15] In the 1950s, real estate agents and speculators employed blockbusting to turn a profit. As a result, formerly middle-class white homes were being turned over to poorer black families. By 1960, eighty-five percent of the population was black.[15]

1960s

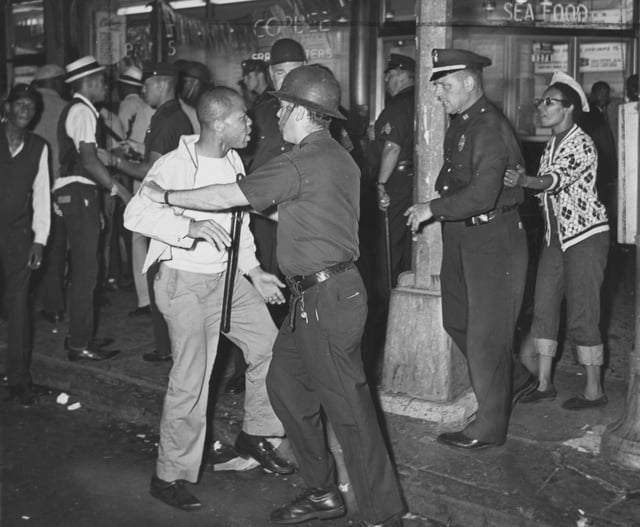

Confrontation between black protesters and police at Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue during the 1964 riot

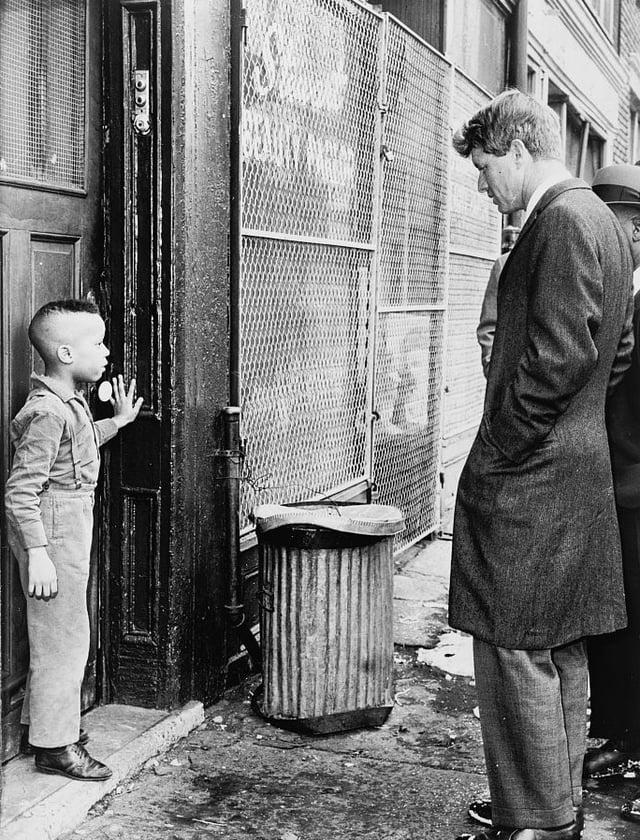

Senator Kennedy speaks with a boy while touring Bedford–Stuyvesant

Gang wars erupted in 1961 in Bedford–Stuyvesant. During the same year, Alfred E. Clark of The New York Times referred to it as "Brooklyn's Little Harlem."[16] One of the first urban riots of the era took place there. Social and racial divisions in the city contributed to the tensions, which climaxed when attempts at community control in the nearby Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district pitted some black community residents and activists (from both inside and outside the area) against teachers, the majority of whom were white, many of them Jewish. Charges of racism were a common part of social tensions at the time.

In 1964, race riots broke out in the Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem after an Irish-American NYPD lieutenant, Thomas Gilligan, shot and killed an African American teenager, James Powell, aged 15.[17] The protest spread to Bedford–Stuyvesant and resulted in the destruction and looting of many neighborhood businesses, many of which were Jewish-owned. Race relations between the NYPD and the city's black community were strained as police were seen as an instrument of oppression and racially biased law enforcement; further, at that time, few black policemen were present on the force.[18] In predominantly black New York neighborhoods, arrests and prosecutions for drug-related crimes were higher than anywhere else in the city, despite evidence that illegal drug-use rates among the black community were at least the same as in the white community, further contributing to the problems between the white-dominated police force and black community. Coincidentally, the 1964 riot took place throughout the NYPD's 28th and 32nd precincts, in Harlem, and the 79th precinct, in Bedford–Stuyvesant, which at one time were the only three police precincts in the NYPD where black police officers were allowed to patrol.[19] Race riots followed in 1967 and 1968, as part of the political and racial tensions in the United States of the era, aggravated by continued high unemployment among blacks, continued de facto segregation in housing, and the failure to enforce civil rights laws.

Following the 1964 election, With the help of local activists and politicians, such as Civil Court Judge Thomas Jones, grassroots organizations of community members and businesses willing to aid were formed and began the rebuilding of Bedford–Stuyvesant.

In 1965, Andrew W. Cooper, a journalist from Bedford–Stuyvesant, brought suit under the Voting Rights Act against racial gerrymandering.[20] The lawsuit claimed that Bedford–Stuyvesant was divided among five congressional districts, each represented by a white Congress member.[21] It resulted in the creation of New York's 12th Congressional District and the election in 1968 of Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman and West Indian American ever elected to the US Congress.[22] In early 1975, when Seatrain Shipbuilding, inside the Brooklyn Navy Yard, laid off a large number of shipbuilders – with 80% of those affected living in and around Bedford–Stuyvesant – it was Congresswoman Chisholm who came to their rescue. Chisholm convinced the government to restructure existing loans and guarantee new loans backed by the VLCC's Stuyvesant and Bay Ridge so the shipbuilders could resume work.

In 1967, Robert F. Kennedy, who was elected US Senator for the State of New York, was tasked on fighting the war on poverty as protests against discrimination broke out across the urban north while the issues of the civil rights movement in southern states were still more of a priority for African American rights activists. Rather than focus on problems facing African Americans outside of New York, Kennedy launched a study of problems facing the urban poor in Bedford–Stuyvesant, which received almost no federal aid and was the city's largest non-white community.[23][24] The Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation was established as the United States’ first community development corporation, envisioned by Kennedy, along with Jacob Javits, Elsie Richardson, Franklin A. Thomas, John Doar, and other activists.[25] The Manhattan-based Development and Services Corporation (D&S) was established, which was composed of business, banking and professional leaders which advised and fundraised private funding for the BSRC's projects.[25] Kennedy's program was soon used as a nationwide model in other large urban areas to fight the War on Poverty.

The abandoned Sheffield Milk bottling plant on Fulton Street was turned into the BSRC offices in 1967; the same year saw the start of the exterior restoration project, which employed local residents to work with contractors to repair facades, restore stoops, fix and replace railings and fences and redo sidewalks.[25] The BSRC bought many housing units in Bedford-Stuyvesant and hired local residents to renovate the units; the BRSC also administered a $73 million mortgage assistance program to encourage African-American homeownership.[25] In 1968, Thomas A. Watson, who was on the board of directors for the D&S, opened an IBM computer cable factory in an abandoned building on the corner of Gates and Nostrand.[25]

As part of the BRSC, architect I.M. Pei implemented a controversial plan to create two superblocks on St. Marks Avenue and Prospect Place, between Kingston and Albany avenues; the project closed the streets off from traffic and cut a pathway mid-block to join the two and fill the street spaces with recreational spaces.[25]

1970s and 1980s

Youth play in an adventure playground at the "K-pool" public swimming pool in Bedford–Stuyvesant in July 1974. Photo by Danny Lyon.

In the late 1980s, resistance to illegal drug-dealing included, according to Rita Webb Smith, following police arrests with a civilian Sunni Muslim 40-day patrol of several blocks near a mosque, the same group having earlier evicted drug sellers at a landlord's request, although that also resulted in arrests of the Muslims for "burglary, menacing and possession of weapons", resulting in a probationary sentence.[26]

Recent history

2000s

The view southeast across Lafayette Avenue, looking toward Patchen Avenue

Beginning in the 2000s, the neighborhood began to experience gentrification.[8] The two significant reasons for this were the affordable housing stock consisting of brownstone rowhouses located on quiet tree-lined streets and the marked decrease of crime in the neighborhood. The latter is partly attributable to the decline of the national crack epidemic as well as heightened policing. Many properties were renovated after the start of the 21st century, and crime declined. New clothing stores, mid-century collector furniture stores, florists, bakeries, cafes, and restaurants opened, and Fresh Direct began delivering to the area. As a result, Bedford–Stuyvesant became increasingly racially, economically, and ethnically diverse, with an increase of foreign-born Afro-Caribbean and African residents as well as residents of other ethnic backgrounds. As is expected with gentrification, the influx of new residents has contributed to the displacement of poorer residents. In other cases, newcomers have rehabilitated and occupied formerly vacant and abandoned properties.

Several long-time residents and business owners expressed concern that they would be priced out by newcomers, whom they disparagingly characterize as "yuppies and buppies [black urban professionals]", according to one neighborhood blog.[29] They feared that the neighborhood's ethnic character would be lost. However, Bedford–Stuyvesant's population has experienced much less displacement of the black population, including those who are economically disadvantaged, than have other areas of Brooklyn, such as Williamsburg and Cobble Hill.[30] Many of the new residents are upwardly mobile middle-income African American families, as well as immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. Neighborhoods surrounding Bedford–Stuyvesant in Northern and Eastern Brooklyn are also majority black, such as Brownsville, Canarsie, Crown Heights, East Flatbush, Flatlands, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, East New York, and Fort Greene. Together these neighborhoods have a population of about 940,000 and are roughly 82% black, making them the largest concentration of African Americans in the United States.[31]

There was a belief that neighborhood change would benefit all residents of the area, bringing with it greater neighborhood safety and more local jobs and creating a demand for improved retail services along the major commercial strips, such as Fulton Street (recently co-named Harriet Tubman Avenue),[32] Nostrand Avenue, Tompkins Avenue, Greene Avenue, Lewis Avenue, Flushing Avenue, Park Avenue, Myrtle Avenue, Dekalb Avenue, Putnam Avenue, Bedford Avenue, Marcy Avenue, Malcolm X Boulevard, Gates Avenue, Madison Street, and Jefferson Avenue. To that effect, both the Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue commercial corridors became part of the Bed-Stuy Gateway Business Improvement District, bringing along with it a beautification project that provides various pedestrian and landscape improvements.[33]

In July 2005, the NYPD designated the Fulton Street–Nostrand Avenue business district in Bedford–Stuyvesant as an "Impact Zone". The designation directed significantly increased levels of police protection and resources to the area centered on the intersection of Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue for a period of six months. During these six months members of notorious gangs such as "Moss Gang" were apprehended. It was renewed for another six-month period in December 2005. Since the designation of the Impact Zone in Bedford–Stuyvesant, crime within the district decreased 15% from the previous year. The police department has ranked Bedford–Stuyvesant as one of the neighborhoods that has experienced a steady decline in crime and has had improved safety. Despite the improvements and increasing stability of the community, Bedford–Stuyvesant has continued to be stigmatized in some circles. In March 2005 a campaign was launched to supplant the "Bed-Stuy, Do-or-Die" slogan with "Bed-Stuy, and Proud of It".[34] Also, the threat of crime taking over certain neighborhoods did not disappear, as violent crime remains a problem in the area. Much like Brownsville and East New York, Bed-Stuy in the early 2000's was known for drive-bys, robberies and assaults. The two precincts that cover Bedford–Stuyvesant reported a combined 37 murders in 2010.[35][36]

2010s

Despite the largest recession to hit the United States in the last 70 years, gentrification continued steadily throughout the neighborhood. The strong community and abundance of historic brownstone townhouses in the neighborhood contribute to its growth. Since 2008 a score of new cafes, restaurants, bakeries, boutiques, galleries, and wine bars have sprung up in the area, with concentrated growth along the western and southern parts of the neighborhood; the blocks north of the Nostrand Avenue and Fulton Street intersection and west of Fulton Street and Stuyvesant Avenues were particularly impacted. In 2011, Bedford–Stuyvesant listed three Zagat-rated restaurants for the first time. Today there are over ten Zagat-rated establishments,[37] and in June 2013, 7 Arlington Place, the setting for Spike Lee's 1994 film Crooklyn, was sold for over its asking price, at $1.7 million.[38]

A diverse mix of students, hipsters, artists, creative professionals, architects, and attorneys of all races continue to move to the neighborhood. A business improvement district has been launched along the Fulton and Nostrand Corridor with a redesigned streetscape to include new street trees, street furniture, pavers, and signage and improved cleanliness in an effort to attract more business investment.[39] Major infrastructure upgrades have been performed or are in progress, such as Brooklyn's first Select Bus Service route, the B44 SBS Bus Rapid Transit service along Nostrand and Bedford Avenues, which began operating in late 2013.[40] Other infrastructure upgrades in the neighborhood includes major sewer and water modernization projects.[41] Verizon FiOS and Cablevision also continue to expand high-speed fiber-optic and cable service to the area.[42] Improved natural and organic produce continue to become available at local delis and grocers, the farmer's market on Malcolm X Boulevard, and through the Bed-Stuy Farm Share.[43] FreshDirect services the neighborhood, and a large member constituency of the adjacent Greene-Hill Food Coop are from Bedford–Stuyvesant.

Subsections

Neighborhoods

Bedford, located toward the western end of Bedford-Stuyvesant. Before the American Revolutionary War times, it was the first settlement to the east of the Village of Brooklyn. It was originally part of the old village of Bedford, which was centered near today's Bedford Avenue–Fulton Street intersection. The area "extends from Monroe Street on the north to Macon Street and Verona Place on the south, and from just east of Bedford Avenue eastward to Tompkins Avenue," according to the Landmarks Preservation Commission.[44][45] Bedford is adjacent to Williamsburg, Crown Heights, and Clinton Hill.[46]

Stuyvesant Heights, located toward the southern-central section of Bedford-Stuyvesant. It has historically been an African-American enclave. It derives its name from Stuyvesant Avenue, its principal thoroughfare. It was originally part of the outlying farm area of Bedford for most of its early history. A low-rise residential district of three- and four-story masonry row houses and apartment buildings with commercial ground floors, it was developed mostly between 1870 and 1920,[46][47][48] mainly between 1895 and 1900.[49] The Stuyvesant Heights Historic District is located within the area bounded roughly by Tompkins Avenue on the west, Macon and Halsey Streets on the north, Malcolm X Boulevard on the east, and Fulton Street on the south.[49][50]

Ocean Hill, located toward the eastern end Ocean Hill received its name in 1890 for being slightly hilly. Hence it was subdivided from the larger community of Stuyvesant Heights. From the beginning of the 20th century to the 1960s Ocean Hill was an Italian enclave. By the late 1960s Ocean Hill and Bedford-Stuyvesant proper together formed the largest African American community in the United States.

Weeksville, located toward the southeast. Weeksville was named after an ex-slave[51] from Virginia, who in 1838[52] bought a plot of land and founded Weeksville.

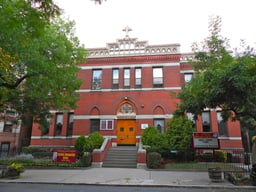

Historic district

The Stuyvesant Heights Historic District in Bedford-Stuyvesant comprises 577 contributing residential buildings built between about 1870 and 1900. The district encompasses 17 individual blocks (13 identified in 1975 and four new in 1996). The buildings within the district primarily comprise two- and three-storey rowhouses with high basements, with a few multiple dwellings and institutional structures. The district includes the Our Lady of Victory Catholic Church, the Romanesque Revival style Mount Lebanon Baptist Church, and St. Phillip's Episcopal Church.[54][55] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 and expanded in 1996.[53] Bedford Stuyvesant/Expanded Stuyvesant Heights Historic District was designated on April 16, 2013 and extended the district north to Jefferson Ave, east to Malcolm X Blvd, and west to Tompkins Avenue.[49]

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Miracle_Temple_Brooklyn.JPG/112px-Miracle_Temple_Brooklyn.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Miracle_Temple_Brooklyn.JPG/169px-Miracle_Temple_Brooklyn.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Miracle_Temple_Brooklyn.JPG/225px-Miracle_Temple_Brooklyn.JPG 2x||h100|w75]]

Miracle Temple

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Decatur_Stuyvesant_Heights_HD_1.JPG/200px-Decatur_Stuyvesant_Heights_HD_1.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Decatur_Stuyvesant_Heights_HD_1.JPG/300px-Decatur_Stuyvesant_Heights_HD_1.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Decatur_Stuyvesant_Heights_HD_1.JPG/400px-Decatur_Stuyvesant_Heights_HD_1.JPG 2x||h100|w134]]

On Decatur Street

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/200_block_Decatur_Brooklyn.JPG/200px-200_block_Decatur_Brooklyn.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/200_block_Decatur_Brooklyn.JPG/300px-200_block_Decatur_Brooklyn.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/200_block_Decatur_Brooklyn.JPG/400px-200_block_Decatur_Brooklyn.JPG 2x||h100|w134]]

On Decatur Street

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/St_Philips_Brooklyn.JPG/200px-St_Philips_Brooklyn.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/St_Philips_Brooklyn.JPG/300px-St_Philips_Brooklyn.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/St_Philips_Brooklyn.JPG/400px-St_Philips_Brooklyn.JPG 2x||h100|w134]]

St. Phillip's Episcopal Church

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_2.JPG/200px-Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_2.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_2.JPG/300px-Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_2.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_2.JPG/400px-Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_2.JPG 2x||h100|w134]]

Mt. Lebanon Baptist Church

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_1.JPG/200px-Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_1.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_1.JPG/300px-Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_1.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bd/Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_1.JPG/400px-Mt_Lebanon_Brooklyn_1.JPG 2x||h100|w134]]

Mt. Lebanon Baptist Church

[[INLINE_IMAGE|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/On_Lewis_Brooklyn.JPG/225px-On_Lewis_Brooklyn.JPG|//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/On_Lewis_Brooklyn.JPG/338px-On_Lewis_Brooklyn.JPG 1.5x, //upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/On_Lewis_Brooklyn.JPG/450px-On_Lewis_Brooklyn.JPG 2x||h100|w150]]

On Lewis Street

Demographic Trends

The 1790 census records of Bedford lists 132 freemen and 72 slaves. Rapid population growth followed major improvements to public transportation. By 1873, Bed-Stuy's (predominantly white) population was 14,000[56]. In the early 1900s, prosperous black families began buying up the mansions of Bed-Stuy, many of which were designed by prominent architects[57]. The population was quick to grow, but it wasn’t until the 1930s that Bed-Stuy’s black population boomed. Following the introduction of the IND Fulton Street Line (a.k.a. the A/C line) in 1936, African-Americans left crowded Harlem in search of better housing opportunities. Bed-Stuy quickly became the second destination for black New Yorkers and the New York Times even dubbed it “Little Harlem” in 1961.

After a large decline during the 1970s (mirroring the citywide decline), the population in Bedford Stuyvesant grew by 34 percent between 1980 and 2015 (faster than the citywide growth rate of 21 percent) to reach 150,900 residents. The population has increased by 25 percent in just the past 15 years, more than three times faster than the citywide rate. The ethnic and racial mix of the population has undergone dramatic changes in the past 15 years as the neighborhood has attracted new residents. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, three-quarters of the residents identified as black or African-American in 2000, but this share had declined to less than half of the population by 2015. In 2015 (the latest year for which census data are available), one-quarter of the residents were white and nearly one-fifth were Hispanic. By comparison, in 2000, less than 3 percent of the population was white (the Hispanic share of the population has remained relatively unchanged). The Asian population has grown, but remains relatively small, making up less than 3 percent of the neighborhood[58] According to the US Census Bureau, in 2016 the population was 49% Black, 27% White, 19% Hispanic, 3% Asian, and 2% other or from two or more races.[4]

The entirety of Community Board 3 had 152,403 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 76.8 years.[59] [] This is lower than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[60] [] [61] Most inhabitants are middle-aged adults and youth: 24% are between the ages of 0–17, 33% between 25–44, and 22% between 45–64. The ratio of college-aged and elderly residents was lower, at 10% and 11% respectively.[59] []

As of 2016, the median household income in Community Board 3 was $51,907.[4] In 2018, an estimated 23% of Bedford–Stuyvesant residents lived in poverty, compared to 21% in all of Brooklyn and 20% in all of New York City. One in eight residents (13%) were unemployed, compared to 9% in the rest of both Brooklyn and New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 53% in Bedford–Stuyvesant, higher than the citywide and boroughwide rates of 52% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018, Bedford–Stuyvesant is considered to be rapidly gentrifying.[59] []

Politics

The neighborhood is part of New York's 8th congressional district,[62][63] represented by Democrat Hakeem Jeffries as of 2013.[64] It is also part of the 18th and 25th State Senate districts,[65][66] represented respectively by Democrats Julia Salazar and Velmanette Montgomery,[67][68] and the 54th, 55th, and 56th State Assembly districts,[69][70] represented respectively by Democrats Erik Dilan, Latrice Walker, and Tremaine Wright.[71] Bed-Stuy is located in the New York City Council's 36th and 41st districts,[72] represented respectively by Democrats Robert Cornegy and Alicka Ampry-Samuel.[73][74]

Police and crime

Bed-Stuy's violent crime fell by 44 percent between 2000 and 2016[76]. The area collectively covered by the 79th and 81st Precincts ranked 62nd safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010. In 2016, major crime dropped 11 percent in the 81st Precinct, marking the greatest reduction in north Brooklyn's 10 precincts.[77] With a non-fatal assault rate of 117 per 100,000 people, Bedford–Stuyvesant's rate of violent crimes per capita is still greater than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 1,045 per 100,000 people is higher than that of the city as a whole.[59] []

The 79th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 78.8% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct saw 9 murders, 27 rapes, 309 robberies, 343 felony assaults, 301 burglaries, 484 grand larcenies, and 72 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[78] The 81st Precinct had a relatively smaller crime decrease of 73.9% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct saw 10 murders, 25 rapes, 234 robberies, 274 felony assaults, 218 burglaries, 399 grand larcenies, and 48 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[79]

Fire safety

The New York City Fire Department (FDNY) operates seven fire stations in Bedford–Stuyvesant:[80][81]

Ladder Co. 102 – 850 Bedford Avenue

Engine Co. 230 – 701 Park Avenue[82]

Battalion 57/Engine Co. 235 – 206 Monroe Street[83]

Engine Co. 217 – 940 DeKalb Avenue[84]

Engine Co. 214/Ladder Co. 111 – 495 Hancock Street[85]

Battalion 37/Engine Co. 222 – 32 Ralph Avenue[86]

Engine Co. 233/Ladder Co. 176/Field Comm Unit 1 – 25 Rockaway Avenue[87]

Health

Preterm and teenage births are more common in Bedford–Stuyvesant than in other places citywide. In Bedford–Stuyvesant, there were 95 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 26.9 teenage births per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide).[59] [] Bedford–Stuyvesant has a relatively low population of residents who are uninsured, or who receive healthcare through Medicaid.[88] In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 11%, which is slightly lower than the citywide rate of 12%.[59] []

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Bedford–Stuyvesant is 0.0081 milligrams per cubic metre (8.1×10−9 oz/cu ft), higher than the citywide and boroughwide averages.[59] [] Nineteen percent of Bedford–Stuyvesant residents are smokers, which is higher than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[59] [] In Bedford–Stuyvesant, 29% of residents are obese, 13% are diabetic, and 34% have high blood pressure—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[59] [] In addition, 22% of children are obese, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[59] []

Eighty-four percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is slightly lower than the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 76% of residents described their health as "good," "very good," or "excellent," slightly less than the city's average of 78%.[59] [] For every supermarket in Bedford–Stuyvesant, there are 57 bodegas.[59] []

Post offices and ZIP codes

Bedford–Stuyvesant is covered by four primary ZIP Codes (11206, 11216, 11221, 11223) and parts of two other ZIP Codes (11205 and 11213). The northern part of the neighborhood is covered by 11206; the central part, by 11221; the southwestern part, by 11216; and the southeastern part, by 11223. In addition, the ZIP Code 11205 covers several blocks in the northwestern corner of Bed-Stuy, and 11213 includes several blocks in the extreme southern portion of the neighborhood.[89] The United States Postal Service operates four post offices nearby: the Restoration Plaza Station at 1360 Fulton Street,[90] the Shirley A Chisholm Station at 1915 Fulton Street,[91] the Bushwick Station at 1369 Broadway,[92] and the Halsey Station at 805 MacDonough Street.[93]

Education

Bedford–Stuyvesant generally has a lower ratio of college-educated residents than the rest of the city. While 35% of residents age 25 and older have a college education or higher, 21% have less than a high school education and 43% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 40% of Brooklynites and 38% of city residents have a college education or higher.[59] [] The percentage of Bedford–Stuyvesant students excelling in reading and math has been increasing, with reading achievement rising from 32 percent in 2000 to 37 percent in 2011, and math achievement rising from 23 percent to 47 percent within the same time period.[94]

Bedford–Stuyvesant's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is higher than the rest of New York City. In Bedford–Stuyvesant, 30% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, compared to the citywide average of 20% of students.[60] [] [59] [] Additionally, 70% of high school students in Bedford–Stuyvesant graduate on time, lower than the citywide average of 75% of students.[59] []

Schools

PS 93, Prescott School

Several public schools serve Bedford-Stuyvesant. The zoned high school for the neighborhood is Boys and Girls High School on Fulton Street. The Brooklyn Brownstone School, a public elementary school located in the MS 35 campus on MacDonough Street, and was developed in 2008 by the Stuyvesant Heights Parents Association and the New York City Board of Education. At the eastern edge of the neighborhood is Paul Robeson High School for Business and Technology.

For the early grades Ember Charter School for Mindful Education and Success Academy Bed-Stuy 1 and 2 are charter schools. Bed-Stuy is also home to the Brooklyn Waldorf School, which moved to Claver Castle (at 11 Jefferson Avenue) in 2011.

Other institutions include:

Boys High School

Girl's High School

Pratt Institute

Brooklyn Brownstone Elementary School

Weeksville Heritage Center

Bedford Academy High School

Libraries

The Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) has four branches in Bedford-Stuyvesant:

The Bedford branch and Bedford Learning Center, at 496 Franklin Avenue near Fulton Street. The branch opened in 1905.[95]

The Marcy branch, at 617 DeKalb Avenue near Nostrand Avenue.[96]

The Macon branch, at 361 Lewis Avenue near Macon Street. The branch is a Carnegie library that opened in 1907. It contains the Dionne Mack-Harvin Center, a collection dedicated to African American culture.[97]

The Saratoga branch, at 8 Thomas S. Boyland Street near Macon Street. The branch is a Carnegie library that opened in 1909.[98]

Transportation

Bedford–Stuyvesant is served by several bus routes operated by MTA Regional Bus Operations. The B7, B15, B43, B44, B44 SBS, B46, B46 SBS, B47, B48 and B60 routes run primarily north to south through the neighborhood, while the B25, B26, B38, B52 and B54 run primarily west to east, and the Q24, B46, and B47 run northwest to southeast on Broadway.[99]

It is served by the New York City Subway IND Fulton Street Line (A and C trains), which opened in 1936. This underground line replaced the earlier, elevated BMT Fulton Street Line on May 31, 1940. The IND Crosstown Line (G train), running underneath Lafayette Avenue and Marcy Avenue, opened for service in 1937. The elevated BMT Jamaica Line (J, M, and Z trains), the city's oldest subway line because of its having opened in 1885, also serves the neighborhood, running alongside its northern boundaries at Broadway. Bedford–Stuyvesant is also served by the Nostrand Avenue and East New York stations of the Long Island Rail Road.

Until 1950, the BMT Lexington Avenue Line served Lexington Avenue in the neighborhood. Likewise, the BMT Myrtle Avenue Line served Myrtle Avenue in the north until 1969.

Notable people

Aaliyah (1979–2001), Grammy-nominated singer.[100]

Aja (born 1994), drag queen and performer

Big Daddy Kane (born 1968), rapper.[101]

Memphis Bleek (born 1978), rapper.[102]

Mark Breland (born 1963), boxer.[103]

Foxy Brown (born 1978), rapper

Lil Cease (born 1977), rapper[104]

Shirley Chisholm (1924–2005), congresswoman[105]

Imani Coppola (born 1978), singer-songwriter[106]

Alan Dale (1925–2002), singer and star of The Alan Dale Show[107]

Deemi (born 1980), singer[108]

Nelson Erazo (born 1977), professional wrestler better known by his ring name Homicide

Fabolous (born 1977), rapper[110]

Bobby Fischer (1943–2008), eleventh World Chess Champion

William Forsythe (born 1955), actor

Jackie Gleason (1916–87), actor, comedian[111]

Carl Gordon (1932–2010), actor[112]

Kadeem Hardison (born 1965), actor, portrays Dwayne Wayne on A Different World[113]

Richie Havens (1941–2013), musician and poet[114]

Connie Hawkins (1942-2017), Basketball Hall of Fame player[115]

Lena Horne (1917–2010), actress and singer[116]

Shawn "Jay-Z" Carter (born 1969), rapper, who lived in the Marcy Housing Projects for most of his childhood[117]

Jaz-O (born 1964), rapper

Joey Badass (born 1995), rapper[118]

Norah Jones (born 1979), singer[119]

June Jordan (1936–2002), Caribbean American poet, novelist, journalist, biographer, dramatist, teacher and activist[120]

Wee Willie Keeler (1872–1923), Baseball Hall-of-Famer[121]

Brian Kokoska (born 1988), artist

Talib Kweli (born 1975), emcee

Maino (born 1973), rapper[123]

Masta Ace (born 1966), rapper

Frank McCourt (1930–2009), a writer, and Malachy McCourt (born 1931), an actor, writer and politician. Frank's autobiographical bestseller Angela's Ashes describes their early childhood life in a working-class apartment building on Classon Avenue.[124]

Frank Mickens (1946–2009), educator[125]

Stephanie Mills (born 1957), singer

Sauce Money, rapper

Tracy Morgan (born 1968), comedian and actor[126]

Mos Def (aka Yasiin Bey) (born 1973), rapper

Ali Shaheed Muhammad (born 1970), DJ, producer and member of A Tribe Called Quest[127]

Jack Newfield (1938–2004), journalist[15]

Harry Nilsson (1941-1994), musician, songwriter and author[128]

The Notorious B.I.G. (1972–97), rapper, grew up near the Clinton Hill-Bed Stuy border, previously considered part of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood.[129][130]

Oddisee, rapper, producer

Ol' Dirty Bastard (1968–2004), rapper

Papoose (born 1978), rapper

Floyd Patterson (1935–2006), boxer

Martha M. Place (1849–99), first woman to be put to death in the electric chair[131]

Jackie Robinson (1919–72), professional baseball player with the Brooklyn Dodgers[132]

Chris Rock (born 1965), actor/comedian.[133] Also made a TV series about his early life, with much of it based in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Tony Rock (born 1974), comedian and younger brother of Chris Rock

Gabourey Sidibe (born 1983), Academy Award-nominated actress

Skyzoo (born 1982), rapper

Brandon Stanton (born 1984), Humans of New York author and photographer

Tek (born 1973), one half of Smif-N-Wessun

Bill Thompson (born 1953), New York City 2013 Mayoral candidate[134]

TRUE (born 1968), artist

Mike Tyson (born 1966), boxer, lived there with his family until the age of 10.[135]

Martha Wainwright (born 1976), singer

Dan Washburn, author of The Forbidden Game: Golf and the Chinese Dream

Whodini, hip-hop group

Lenny Wilkens (born 1937), Basketball Hall of Fame player and coach[136]

Juan Williams (born 1954), journalist and political analyst

Ted Williams (born 1957), voiceover artist

Vanessa A. Williams (born 1963), actress

In popular culture

Billy Joel's 1980 song "You May Be Right," from his album Glass Houses, includes "I walked through Bedford-Stuy alone" among the foolhardy things the song's narrator has done.[137]

In her 1980 one-woman film Gilda Live, Gilda Radner included a sketch featuring her Emily Litella character working as a substitute teacher in Bedford-Stuyversant, filling in for a teacher who'd been stabbed by one of his students.[138]

Notorious B.I.G., a rapper who included Bed–Stuy in his lyrics,[129] he "publicly claim[ed] Bedford-Stuyvesant as his neighborhood".[140] A 2009 film, Notorious, about life in Bed–Stuy in the 1990s, emphasized Notorious B.I.G.[141]

Empire State of Mind by Jay-Z and Alicia Keys has the line "Me, I'm out that Bed-Stuy, home of that boy Biggie"

The television show Everybody Hates Chris was partially based in Bed-Stuy.

The 2009 movie "Brooklyn's Finest" was partially set and filmed in Bed-Stuy.

The 2011 Jay-Z song "Gotta Have It," which features Kanye West, contains the lyrics "Made a left on Nostrand Ave, we in Bed-Stuy".

Bed-Stuy is the main setting of Rita Williams-Garcia's novel P.S. Be Eleven.

In the 2012 volume of Hawkeye, Clint Barton lives in and assumes ownership of an apartment in Bed-Stuy, which provides the main setting for the comic.

The song "Hurricane," by Halsey mentions the neighborhood Bed-Stuy several times "there's a place way down in Bed-Stuy, where a boy lives behind bricks." Additionally, Halsey's stage name is both an anagram of her actual name 'Ashley', and also named after the street in that neighborhood.

The song "First Person on Earth" by Robert DeLong includes a line about Bed-Stuy: "I caught a redeye, out to Bed-Stuy to get your lovin'"[142]